We Found The Names of Radioactive Waste Locations That Government Kept Secret

We Found The Names of Radioactive Waste Locations That Government Kept Secret

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

SUPPORT newsCOUP

Public Herald is a nonprofit newsroom that holds those in power accountable.

You can receive our latest breaking stories by subscribing to our newsletter

or becoming a Public Herald Patron.

by Jake Conley for Public Herald, From Editors Joshua Boaz Pribanic and Melissa A. Troutman

January 24, 2022 | Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers, TENORM Mountains

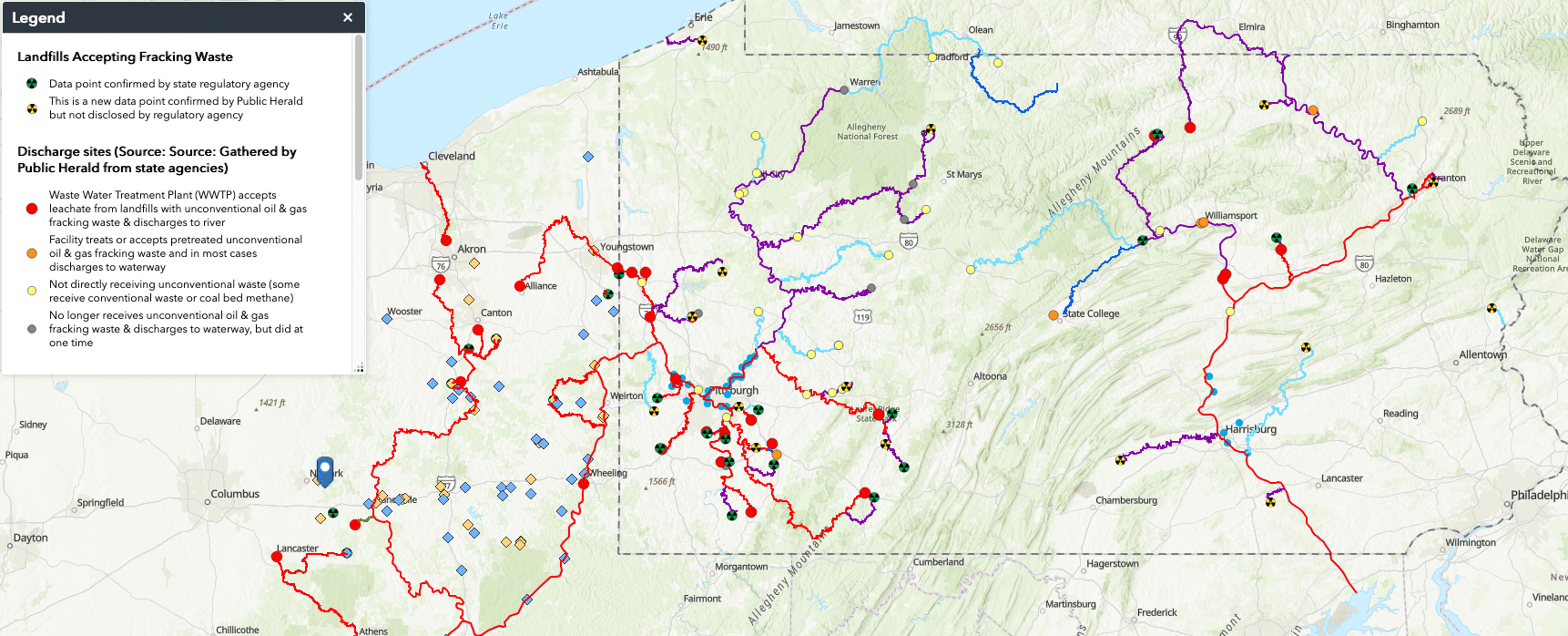

Radioactive Oil & Gas Test Sites Uncovered & Mapped by Public Herald

For about six years, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has obscured the radioactive hazards of oil and gas operations. Ever since the 2016 release of its study on oil and gas TENORM — technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material — the DEP has kept the names and locations of where radioactive waste was detected a secret and told the general public there was little to worry about.

The question is, does the radium in the raw data tell a different story?

When the Department chose not to release the names of the 144 locations tested in the 2016 study, it blocked the public’s ability to make place-based, local decisions about potential threats from TENORM.

Now, for the first time, all 144 names and locations are being released by the team at Public Herald. We’ve mapped the landfills, centralized waste treatment facilities, publicly owned treatment works, zero-liquid discharge facilities, brine-treated roads, well pads and their test results for radium from the DEP’s study.

For Public Herald’s analysis, we focus on radium (Ra-226 & Ra-228) because it is federally regulated for its health impacts, highly soluble in water and a lead indicator of TENORM contamination. The DEP’s TENORM analysis tested the following elements: U-235, U-238, Ra-226, Ra-228, Th-232, Ac-228, Pb-212, Bi-212, and K-40.

Using the TENORM study interactive map, the public can finally see the locations Pennsylvania officials withheld. Knowing the location of specific radium results from the DEP’s TENORM study is critical to evaluating the health impacts of oil and gas radioactivity in studies like the one currently underway by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC).

caption: The DEP TENORM study’s locational data was released to Public Herald by the DEP in July 2021 following a Right-to-Know request and a subsequent appeal to the Pennsylvania Office of Open Records after the Department provided Public Herald with an incomplete set of information.

Public Herald has been investigating TENORM, a radioactive waste product of oil and gas operations, since 2011, pulling up the blinds on the frontline and downstream impacts and the government and industry actors that allow and encourage their proliferation.

Public Herald’s Pennsylvania TENORM map provides the premier interface with which to visually review the radium data from the DEP’s TENORM study. Our team organized all 144 locations tested into six categories, each represented by a unique icon on the map.

When hovered over, icons on the map (corresponding to the legend) will provide the name of that facility and a sample of that specific facility’s radium data.

The layers button in the top left of the map window allows the user to add an overlay of Pennsylvania’s watersheds, which are shared with neighboring states and communities downstream.

The bottom of the map also has a link to the full dataset containing all data on radium collected during the DEP’s TENORM study. This spreadsheet is composed of four sheets (accessible by tabs at the bottom of the screen) — one for the three kinds of wastewater treatment facilities (CWTs, POTWs, and ZLDs), one for landfills, another for roads that received “beneficial reuse” brine treatment, and one for well pads. All sheets contain the full data for radium tests at every facility or location where measurements were taken for the study.

THE REAL STORY ON RADIOACTIVITY

When the DEP released its TENORM study in 2016, it told the public, “There is little potential for harm to workers or the public from radiation exposure due to oil and gas development.”

In September 2021, at a legislative policy hearing on closing the state’s loophole for radioactive oil and gas waste, DEP oil and gas Deputy Secretary Scott Perry stated, “I don’t think any other state has done more to monitor and address this issue.”

But while safety and due diligence are the messages the DEP continues to push, the reality of Public Herald investigations from the DEP’s own data is one of mass contamination of the environment and risk to Pennsylvania’s drinking water and public health.

Though oil and gas waste contains hazardous materials, most of it is exempt from hazardous waste law by the EPA. TENORM from oil and gas operations is also not covered by other regulations governing radioactive material either, including the federal Atomic Energy Act.

In spite of the lack of proper regulation, oil & gas waste contains radionuclides like radium-226, a cancer-causing element with a half-life of 1,600 years, among other radioactive materials, like uranium and lead-210, which the industry has known about for over 50 years.

The EPA’s maximum allowed concentration of radium-226 for safe drinking water is just 5 picocuries per liter (pCi/L). Many of the results from the DEP’s TENORM study, including ones for waste being dumped into rivers, greatly exceed the EPA’s safety standard.

What the TENORM study raw data shows is that Pennsylvania’s citizens are living among larger quantities of oil and gas radioactivity than officials have let on. After analyzing the DEP’s radium test results and locations, here are some of Public Herald’s major takeaways:

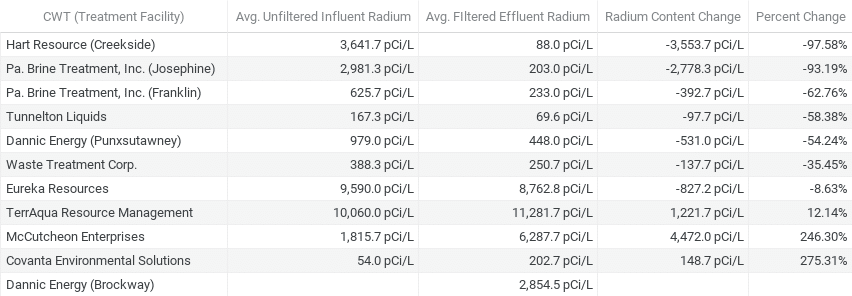

Centralized Waste Treatment Facilities (CWTs): 11 mapped

Across Pennsylvania, there is a system of facilities that take liquid waste from fracking sites and theoretically clean it, stripping out all harmful contaminants. However, the TENORM study data shows that treatment facilities are often not removing even half, or in some cases any, radioactivity before fracking waste is discharged to rivers.

The key facilities guilty of this are centralized waste treatment facilities, or CWTs. CWTs are facilities owned by private companies, such as Eureka Resources, who are permitted by the state and federal government to treat and “clean” fracking waste in-house. But in reality, most CWTs are not doing the job, and some are actually making the waste hotter.

At three facilities in the DEP’s TENORM study, oil and gas wastewater tested higher on average for radium levels after treatment. At two facilities, treated waste tested over 200% higher on average for radium than before treatment: McCutcheon Enterprises (Apollo, Armstrong Co.) and Covanta (New Castle, Lawrence Co.). Only five CWTs were able to remove on average over 50% of the radioactivity, and only two out of 11 facilities managed to cut down radium on average by more than 90%. That means that radioactive wastewater coming in is still radioactive after treatment and being discharged to rivers at levels far above drinking water standards — and it’s all being permitted by the DEP.

Chart: A comparison of radium levels in unfiltered influent (raw waste) vs. filtered effluent (treated waste) in centralized wastewater treatment (CWT) facilities. No radium test results for unfiltered influent at the Dannic Energy (Brockway) CWT were provided in the DEP’s TENORM study. Public Herald TENORM Map.

The DEP’s TENORM study itself states, “Radium was routinely detected in all sample types with little difference between influent and effluent or between filtered and unfiltered results.” (Effluent is the “treated” final product going out of treatment facilities; influent is the raw wastewater coming in.) However, the DEP has buried this fact from its press materials about the study and failed to study the impacts occurring as a result of their findings.

For context, the EPA noted in its own 2018 study on fracking that “CWT facilities treating O&G wastewater and discharging to surface waters have direct and measurable impacts on downstream surface waters and sediment.”

caption: Covanta Environmental Solutions, a centralized waste treatment plant operating out of New Castle, Pa. and treating radioactive fracking waste through a permit from PA DEP. According to effluent samples in DEP’s 2016 TENORM study, Covanta’s system is creating four times as much TENORM after treatment. © Nina Berman for Public Herald

Throughout 2022, Public Herald’s TENORM investigations will continue showcasing how and where CWTs are failing to control radioactivity from fracking waste.

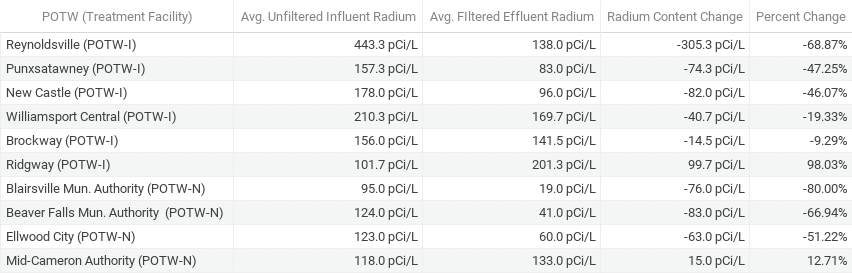

Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTWs): 10 mapped

Publicly owned treatment works (POTWs), such as local sewage facilities, face an identical problem as the CWTs, according to the DEP’s data. POTWs are the publicly owned complements of CWTs and permitted by the DEP to discharge treated wastewater such as stormwater, sewage, and landfill leachate. POTWs that accept oil and gas waste containing radium-226 and radium-228 theoretically dilute the radioactivity, but it is not actually removed — a situation that experts say leads to radioactive legacy pollution.

Since both radium-226 and radium-228 are water-soluble, these radionuclides leach out of oil and gas waste sitting in landfills after it rains, creating a new liquid waste stream called leachate.

According to Public Herald reports, nearly all landfill leachate in Pennsylvania is sent to POTWs that, in most cases, cannot filter out radioactive material before discharge to public waterways. The EPA confirms this in its 2018 study: “Treatment processes at POTWs are not effective at removing all types of pollutants in O&G wastewater.”

The raw data from the DEP’s TENORM study confirms this as well:

The POTWs tested in the DEP TENORM study that are accepting oil and gas wastewater only lowered the radium content on average by 9.3% to 69%.

Even though Reynoldsville POTW (Jefferson Co.) was able to lower radium by 69% on average, its effluent waste for discharge still contained 138 pCi/L of radium. Reynoldsville discharges into local streams: Sandy Lick Creek, Pitchpine Run, Soldier Run.

What’s worse, the level of radium in waste being discharged to the Clarion River by the Ridgway POTW (Ridgway, Elk Co.) nearly doubles after treatment, increasing radium by 98% on average compared to the waste coming into the facility.

The POTWs tested for the TENORM study that are not accepting oil and gas wastewater are discharging the lowest amounts of radium on average, with the exception of Mid-Cameron (Emporium, Cameron Co.), which is discharging treated waste that is hotter than the raw waste going in.

Chart: A comparison of radium levels in unfiltered influent (raw waste) vs. filtered effluent (treated waste) in Publicly Owned Treatment Works. “POTW-I” = influenced, accepting oil & gas waste. “POTW-N” = non-influenced, not accepting oil & gas waste. TENORM Map.

While some radium levels are lower after treatment at POTWs, the problem is identical as with the CWTs – wastewater exiting the facilities is more radioactive than safety standards allow.

In the TENORM study itself, the DEP recognizes a visceral environmental impact from POTWs that accept oil and gas waste: “There is a radiological environmental impact to soil from the sediments from POTW-I’s.” (POTW-Is” are facilities that accept oil and gas waste.)

But again, the DEP buried this lead in its public statements about the study.

Megan Hunter, a senior attorney with the environmental legal firm Earthjustice, explained in an interview with Public Herald how one lawsuit against a POTW and CWT in Ohio illustrated the way this wastewater-shuttling system can easily break down.

“The salt alone from this kind of waste can really wreak havoc on a wastewater treatment plant in a way that takes the facility months or years to fix, ” Hunter said. “The centralized waste treatment [CWT] facility was violating its user permit, and then it was also discharging to the publicly owned treatment works [POTWs] and causing it to violate its discharge permit as well.”

Become A Public Herald Patron

To Listen To The Full Interview With

Earthjustice Lawyer Megan Hunter »

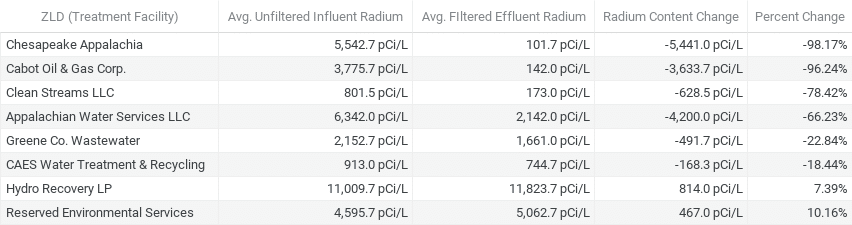

Zero-liquid Discharge Facilities (ZLDs): 8 mapped

The threat of radioactive harm continues even at facilities not discharging wastewater effluent, in this case zero-liquid discharge facilities (ZLDs).

The raw data in the DEP’s TENORM study is yet again clear — ZLDs are radioactive waste sites. The data shows ZLDs, which use distillation and chemicals to process fracking waste for reuse, often clocking levels of radioactivity in the thousands of pCi/L, and even though they aren’t discharging waste into waterways, the waste is trucked along public roads to other sites.

Out of the ZLDs tested in the DEP TENORM study, half of them failed to remove even 50% of the radium from oil and gas wastewater on average, and two outputted waste even more radioactive than what came in: Filtered waste at Hydro Recovery ZLD in Blossburg (Tioga Co.) showed an average 7.4% increase in radium. Elevated results there reached an average 11,800 pCi/L. Also, filtered waste at Reserved Environmental Services in Mt. Pleasant (Westmoreland Co.) increased over 10% in radium on average while at the facility to an average of over 5,000 pCi/L.

Chart: A comparison of radium levels in unfiltered influent (raw waste) vs. filtered effluent (treated waste) in ZLDs. TENORM Map.

The DEP’s TENORM study states, “Radium was routinely detected in all liquid influent and effluent sample types with an approximate 50 percent difference between influent and effluent, but little difference between filtered and unfiltered results.”

Landfills: 51 mapped

Across the landscape in Pennsylvania, the mapped radium data shows DEP permits have created mountains of radioactivity in the form of landfills accepting thousands of tons of oil & gas waste, some within close proximity to homes, neighborhoods, school districts and other municipal areas, and the radioactivity increases by the year.

Dr. Julie Weatherington-Rice, a soil scientist and adjunct professor for Ohio State University, is clear about the danger these mountains — and state-sanctioned practices — pose.

“This is a permanent reactor near your house, and it will always be a reactor because the waste got pooled together. And it will make as much radon and radium today as it will tomorrow and the next day … and 500 years from now … So while it’s a naturally occurring material, when you concentrate it [in landfills], you create a reactor.”

The TENORM location data also reveals that the DEP has allowed three landfills to discharge highly radioactive leachate directly to streams.

For the TENORM study, the DEP identified nine landfills that had taken the largest amount of oil and gas TENORM waste the year before. Of those nine, the DEP targeted three for additional sediment sampling because they discharge their leachate effluent directly into the environment. Those three landfills, their leachate effluent results from the TENORM study, and the streams that the DEP allowed them to discharge radioactive leachate to are outlined below (stream names were pulled by Public Herald from facility NPDES permits, which were not included in the TENORM study.):

Seneca Landfill (Evans City, Butler Co.)

123.000 pCi/L radium-226

Discharged to Connoquenessing Creek

caption: Public Herald’s TENORM Leachate Map illustrates where (in red) radioactive waste from fracking is escaping into public waters, and where (trefoil symbol) it’s being stored in Pennsylvania. The 2019 report discovered a statewide system of TENORM being released from landfill leachate to POTWs, and the investigation was updated in 2020 with a new map. Click for interactive map »

The combined radium levels in leachate from the top oil and gas TENORM landfills by volume, according to the DEP at the time of the TENORM study, range from 29 pCi/L (Northwest Landfill in West Sunbury, Butler Co.) to 422 pCi/L (Evergreen Landfill in Blairsville, Indiana Co.).

For a previous investigation, Public Herald asked the DEP where the leachate from each landfill accepting oil and gas waste ends up, but so far the department has only disclosed where 34% of it is going. The destination of the remaining 66% of leachate remains unknown. Why? The DEP is not tracking how much TENORM is leaving landfills and being discharged to waterways through POTW facilities. The DEP says this transaction is “private” between the two entities: the landfill and the POTW facility.

Despite the DEP’s data pointing to ever-increasing cumulative TENORM concentrations in landfills and leachate, Pennsylvania continues to build these TENORM mountains and allow leachate to be discharged to rivers.

“You can look up and down any water body, and you have dischargers violating their permits all the time,” Hunter, the Earthjustice attorney, told Public Herald, “and agencies get to basically pick their enforcement priorities, and who they’re going to go after and bring into compliance.”

In Pennsylvania, this means that the DEP has the discretion to prohibit companies from discharging radium over 5 pCi/L, but instead they are choosing not to include that level of protection and allow high levels of radium to enter waterways via leachate.

Road Locations: 44 mapped

Brine, another liquid waste from oil & gas operations, has historically been spread on roads across Pennsylvania as dust suppressant and de-icer, creating yet another pathway for radioactive oil & gas waste to potentially harm the environment.

The TENORM study test results are broken into two categories: “road biased soil” and “reference background road.” Theoretically, the background samples are meant to establish a baseline level of radium to compare with road soil samples from areas where brine has been spread. Unfortunately, the background samples are largely useless and cannot be used as a baseline comparison for roads with known brine treatment because the “background” sections of road could have been treated with brine as well, as the DEP notes in the TENROM study:

“The average excess Ra-226 for roads identified as having been O&G brine-treated is 1.13 pCi/g compared to an average of 8.23 pCi/g on the background reference roads. One possible explanation is that all of the roads have been treated with O&G brine.”

Because all road soil and background samples from the TENORM study are from areas of potential or known spreading, we’ve focused on the combined radium results as a whole, which ranged from less than 1 picocurie per gram (pCi/g) to over 74 pCi/g. For context, the EPA recommends that radium-contaminated sites are cleaned up until there is only 5 pCi/g left in soil.

According to a study from the University of Pittsburgh, the risks communicated to the public about the 2016 TENORM study were misleading, since the DEP did not communicate or accurately calculate the safety of residential exposure to radium around brine-treated roads, and instead relied on limited “recreational” exposure.

Looking at the implications of the use of radioactive brine on roads, the scientists explained that if radium is concentrating at levels as high as results for radium in the DEP’s study (i.e. 60 pCi/g), Pennsylvania residents living in and around those roads could be exposed to a level of radium that far surpasses national safety standards of 100 millirem per year.

Though the exposure in one instance may be insignificant, the UPitt study also states, regular use of brine on roads could lead to an accumulated exposure for those nearby that could exceed levels considered safe.

Well Pads: 20 mapped

Oil and gas well sites produce several types of waste, all of which can contain TENORM. Out of the well sites surveyed in the DEP’s TENORM study, the average level of radium-226 in drilling fluids was 2,990 pCi/L. In fracturing fluid, the average level was 5,287.81 pCi/L; and in flowback fluid, the average was 8,489 pCi/L.

Solid TENORM waste arriving at landfills from well pads drilling into the Marcellus Shale detected radium levels from fracking waste drill cuttings as high as 13 pCi/g, more than 2.5 times greater than federal guidance permits for soil remediation (i.e. 5 pCi/g).

However, in an analysis of the TENORM study, nuclear physicist Martin Resnikoff suggests that the DEP could have manipulated the data:

“It appears as though cuttings from lower-emitting, outlier wells were selected for sampling, or that the average was brought down by non-Marcellus [Shale] cuttings,” adding that “[the DEP] results [are] completely out of line with measurements by the USGS and measurements by NYSDEC in 2012 of rock cuttings from Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, of Cabot Oil and Gas Co. from a Marcellus shale well. High radium-226 concentrations of rock cuttings transported to a Niagara County landfill, up to 204 pCi/g Ra-226 in two train carloads of rock cuttings, were returned to Cabot Oil and Gas Co.”

Knowing the levels of radioactivity coming out of specific locations from the TENORM study helps us understand who may be at increased risk of exposure near these particular well sites. But Pennsylvania has hundreds of thousands of oil and gas wells, some of which are leaking.

The Reese Hollow #118 shale gas well, aimed for testing the Utica formation, where JKLM began drilling operations on August 28, 2015 according to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP). One month after drilling, illegal chemicals were released underground that contaminated over six drinking water supplies. The contaminants also showed up in two public water supplies that the DEP investigators dismissed as being related to drilling, information published by Public Herald that DEP kept from the public. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

According to the DEP’s 2020 Annual Report, Pennsylvania has over 30,000 active wells, 12,096 documented orphaned and abandoned wells, and approximately 200,000 undocumented orphaned and abandoned wells. Historically, Pennsylvania has allowed companies to bury drill cuttings onsite, and hold liquid waste in pits that have leaked into soil and groundwater. All of these sites likely contain some measure of radioactivity, as noted by the industry itself. In 1982, the American Petroleum Institute commissioned a report which states:

“Almost all materials of interest and use to the petroleum industry contain measurable quantities of radionuclides that reside finally in process equipment, product streams, or waste, it is reasonable to consider all oil and gas sites, whether for production or waste disposal, contain radioactive material.”

The amounts, and many locations, of all this radioactive oil and gas material are still unknown. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania continues to permit new oil and gas sites by the hundreds every year.

DEP’s Systemic Failure

The DEP’s 2016 TENORM study is proof of a state-sanctioned system whereby radioactive oil & gas waste is shipped around the state to accumulate within communities, contaminate the environment, and put public health at risk.

But, let’s not forget that the DEP’s study is not the whole story. There is a growing body of data from other sources that reveals the ubiquitous nature of the radioactive threat from oil and gas. For example, in October 2020, Harvard University researchers found that airborne radiation is higher near fracking sites, sometimes 40% higher than background levels for those living within 12 miles.

Pennsylvania State Sen. Katie Muth had a simple name for the DEP’s system for dealing with oil and gas radioactivity. In an interview with Public Herald, she called it “organized crime.” With the release of this map, we at least have a better idea of where it’s being ‘organized.’

Unlike the watered-down conclusions made in the DEP’s public relations, the raw data from the Department’s 2016 TENORM study tells a dangerous story that is echoed by Public Herald investigations since 2011, an audit of the DEP by PA Auditor General Eugene DePasquale in 2014, and conclusions of Pennsylvania’s 43rd Statewide Grand Jury report in 2020 — all of which prove that, for over a decade, the commonwealth has ignored and failed to address the inherent dangers of radioactive oil & gas operations.

According to Megan Hunter at Earthjustice, parallel problems exist at the national level and across other state agencies and governments.

“In 2019, the EPA [reviewed its oil and gas waste policy regulations], and they again … determined that everything was fine – ‘We don’t need any new regulations’ – but one thing that they cited to in that determination again and again was this lack of data regarding harm done by oil and gas waste and regarding radioactivity in oil and gas waste. That’s an excuse we’re hearing again and again at agencies, and they’ve used it as an excuse to not do anything.”

When Hunter looked at Public Herald’s TENORM map for this report, her reaction was simple: “There’s just so much work that needs to be done.”

Investigative Journalist Elijah Labby contributed to this story

Funding for this series was made in part by Public Herald Patrons

PUBLIC HERALD’S METHODOLOGY

In the DEP’s published study results — Appendix C: Gamma Spectroscopy Analytical Results — each data point is given a label. For example, the label “WT-01-LQ” signifies that the location where the data point was collected handles waste treatment (WT) and that the data point is from a measurement of a liquid substance (LQ). This data point, in the Gamma Spectroscopy Analytical results, is listed under “CWT Filtered Effluent,” signifying that the measurement was collected from the filtered effluent — or the liquid being released from a facility — of a centralized waste treatment facility (CWT).

The labels, however, do not disclose the location at which the measurement was taken. For WT-01, corresponding to the Josephine Brine Treatment facility, the first listed “waste treatment” facility in the study, gives no indication of its relation to its facility.

To create our interactive map, Public Herald journalists matched each data point in the study by its label to the corresponding location identified in the key the DEP provided to Public Herald. All averages are derived from standard average calculations performed within each substance category for each test location.

The watershed data used is from the United States Geological Survey’s national watershed GIS dataset. The Pennsylvania county lines are taken from the Pennsylvania state government’s county parameter GIS dataset.

The map is built on Tableau Public.

Public Herald’s analysis of the DEP’s TENORM study specifically focuses on radium. We chose to focus solely on radium out of the elements tested in the study due to its studied health risks, high level of solubility and use as a main indicator for TENORM levels.

Company Names & Locations:

(listed numbers below are not related to numbers in data sheet entries)

Landfills

- Greentree

- Clinton Co.

- Lycoming Co.

- Tullytown

- Grows North

- SE Chester Co.

- Chrin Bros.

- Bethlehem

- Brunner

- Allied

- Sandy Run

- Mountain View

- Blue Ridge

- Frey Farm

- Conestoga

- Western Berks

- Pioneer Crossing

- Delaware Co.

- Greater Lebanon

- Harrisburg

- Chester Co.

- Phoenix Resources

- Paris

- Pine Grove

- Pottstown

- Advanced Disposal Services

- McKean

- Northwest

- Seneca

- Arden

- Westmoreland Sanitary

- Chestnut

- Laurel Highlands

- Southern Alleghenies

- Lakeview

- Bradford, Co.

- Alliance

- Keystone Sanitary

- Grand Central

- Commonwealth

- South Hills

- Kelly Run

- Monroeville

- Valley

- Evergreen

- Shade

- Mostoller

- Greenridge

- Cumberland

- Modern

- White Pines

CWTs

- Pennsylvania Brine (Josephine)

- Hart Resource (Creekside)

- Tunnelton Liquids

- Pennsylvania Brine (Franklin)

- Waste Treatment Corp.

- McCutcheon Enterprises

- Eureka Resources

- Dannic Punxsutawney

- Covanta Environmental Solutions

- Dannic Energy (Brockway)

- TerrAqua Resource Management

POTWs

- New Castle

- Ridgway

- Punxsutawney

- Reynoldsville

- Williamsport Central

- Brockway

- Ellwood City Wastewater Treatment

- Beaver Falls Municipal Authority

- Blairsville Municipal Authority

- Mid-Cameron Authority

ZLDs

- Clean Streams, LLC

- Chesapeake Appalachia, LLC, Sharer

- Hydro Recovery LP

- Reserved Environmental Services

- Appalachian Water Services, LLC

- CAES Water Treatment & Recycling

- Greene Co. Wastewater

- Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. / COMTECH

Well pads

- Chesapeake Energy, Yengo Sul Pad

- Range Resources, Cravat Coal B

- Range Resources, MCC Partners

- Shell, Delany

- Shell, Warrant 2916

- Shell, Palmer

- Shell, Lot 6

- Range Resources, Claysville SC

- Range Resources, Zappi, E

- Chesapeake Energy BKT Bra

- Shell, Neal

- Shell, Guillame

- Chesapeake Energy, Visneski

- Seneca Resources, Sulgar

- Range Resources, Harmon Creek D

- Shell, JW Hodgens

- Shell, Seneca

- Shell, Lot 141/143

- Shell, Warrant

- Shell, Site 4