“A Permanent Reactor” Fracking’s Radioactive Health Threat to Ohio Will Last 1,600 Years Without Action

“A Permanent Reactor” Fracking’s Radioactive Health Threat to Ohio Will Last 1,600 Years Without Action

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

SUPPORT newsCOUP

Public Herald is a nonprofit newsroom that holds those in power accountable. You can receive our latest breaking stories by subscribing to our newsletter or becoming a Public Herald Patron.

by Talia Wiener for Public Herald, From Editors Joshua Boaz Pribanic and Melissa A. Troutman

August 02, 2021 | Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers, TENORM Mountains

Oil and gas wells produce radioactive material, defined by the federal government as TENORM – technically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material. But as reported in the first two parts of this series, Ohio is letting TENORM accumulate across the state with virtually no oversight, putting drinking water sources, waterways, and communities at risk.

The legacy of pollution from TENORM cannot be understated. The TENORM from oil and gas contains levels of radium-226 that far exceed state or federal regulations. Since the half-life of radium-226 is 1,600 years, that means it will take 16 centuries for one-half of the nuclei of a radium particle to decay inside of an Ohio waterway.

caption: Kayakers and paddleboarders at Walborn Reservoir, 11324 Price Street NE, in Alliance, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Despite efforts from environmental organizations to educate the public about the radioactive risks created by the boom in shale gas fracking since the early 2000’s, or documentaries from Public Herald like Triple Divide (2013), Triple Divide [Redacted] (2017), and INVISIBLE HAND (2020) that covered radioactive waste, some Ohioans remain unaware of the TENORM piling up in their own backyards.

Sil Caggiano, Senior Battalion Chief for the Youngstown Fire Department, blames the lack of awareness on the state’s protection of the industry. “It’s the third rail of politics here in Ohio,” said Caggiano. “You don’t screw with the fracking.”

Caggiano says his fellow first responders and civilians are not being given the knowledge owed to them by the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, also known as SARA Title III. The Act requires that states “organize, analyze and disseminate information on hazardous chemicals to local governments and the public.” The lack of transparency places Caggiano and his fellow first responders in danger. They have no way to navigate industry-related incidents, like spills and explosions, when they don’t know what to test for or what they are being exposed to.

caption: Austin Masters Services (AMS), a Chief’s Order facility permit at 801 First Street in Martins Ferry, Ohio — permits that go largely untracked. Several of the AMS buildings are reflected in the mirror. The company’s mailbox is visible on the right. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Cagginao is wary of the industry’s money and power to buy ‘experts’ and politicians. When it comes to influencing public opinion, he thinks the industry is nearly impossible to compete with.

“If you bring in some guy that tries to tell you that the radium in the brine tanks is no worse than the radioactive potassium of bananas, people believe it because some guy who got paid and has got a Ph.D. said it,” Caggiano said.

Previous reporting from Public Herald has shown that health risks related to fracking waste exposure do in fact exist — it’s not bananas. The industry, though, with help from the state, has chosen to downplay or ignore risks to both workers in the fracking industry and locals who live near oil and gas sites, treatment plants and sewage systems.

When a radioactive element “decays” it blasts off a tiny explosive piece of matter or energy – what we know of as “ionizing radiation.” Radioactive elements, such as radium-226, emit alpha particles that can become airborne as dust, drift through the air, or be blown about by the wind to be inhaled or ingested. Once inside the human body, an alpha particle’s explosive charge can shred DNA to pieces, causing mutations in genetic material that can potentially affect future generations and obliterate cellular structures, creating the possibility for the development of tumors that can lead to fatal cancers.

Radium-226 is commonly found in oil and gas waste and equipment, especially in the Marcellus and Utica Shale regions, and is known to cause cancer in humans. Research has found exposure to high levels of radium can cause malignant bone tumors, such as childhood bone cancer.

Andrew Gross, who worked as a health physicist with the Navy and has studied the effects of TENORM for years, said the following about the practice of moving TENORM and other radioactive materials to municipal sites like landfills and sewage treatment plants, which is what happens in Ohio:

“Putting this radioactive material into municipal waste sites is a giant concern. That could be life-altering for a lot of people, people in the vicinity, people downwater of streams, all those things.”

caption: Radiation expert Andrew Gross unpacking testing equipment for TENORM at a landfill accepting Marcellus Shale waste. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

Dr. Julie Weatherington-Rice, an earth scientist and adjunct professor for Ohio State University with a Ph.D. in soil science, expressed a similar sentiment:

“This is a permanent reactor near your house, and it will always be a reactor because the waste got pooled together. And it will make as much radon and radium today as it will tomorrow and the next day and the next day and 30 years from now and 100 years from now and 500 years from now because the half life of this stuff is like, forever … So while it’s a naturally occurring material, when you concentrate it, you create a reactor.”

To local families, the horror that follows after learning about how TENORM is mishandled in Ohio is only exacerbated by the fact that both the industry and government have known what was going on the whole time, and have simply turned a blind eye.

Susie Beiersdorfer of Youngstown is a notorious activist with Frackfree Mahoning Valley and the Ohio Community Rights Network. For years, she and her late husband, Ray Beiersdorfer, sat at regulatory agency meetings and watched as the complaints of community members went ignored.

caption: Susie Beiersdorfer beside the Duck Creek Energy well pad in Tod Homestead Cemetery, in Youngstown, Ohio. The well is known for producing radioactive waste, even though it is only a conventional well. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Beiersdorfer takes issue with the close ties between the oil and gas industry and the state government. FrackFree Mahoning Valley has gotten fracking bans on the Youngstown ballot eight times since 2013 in order to protect water and create a community bill of rights All of their efforts have been ultimately unsuccessful and vigorously opposed by the industry and its political operatives.

“We actually did have, at first, the illusions of our government protecting us,” she said. “But we learned that they’re all captured.”

caption: Susie Beiersdorfer in her garden outside her home in Youngstown, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

A Captured Government

Ohio already has a criminal legacy when it comes to government and energy.

In July 2020, Ohio House Speaker Larry Householder and four associates were arrested in a $60 million federal bribery case connected to Ohio’s nuclear power plants. The case was described by a U.S. State Attorney as “the largest bribery and money-laundering scheme that had ‘ever been perpetrated against the people of the state of Ohio.’”

Ohio, like Pennsylvania, has the option for communities to pass Home Rule Charters and ban things like TENORM or waste injection wells. But unlike Pennsylvania, Ohio’s right to local bans has been repeatedly threatened by local Election Boards’ decisions.

On October 6, 2020, plaintiffs from seven Ohio counties filed an appeal in a federal civil rights case challenging the constitutionality of Ohio’s ballot access scheme, which has been manipulated to thwart local democratic efforts to create local bans on radioactive TENORM waste. Represented by the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), the plaintiffs sued the Ohio Secretary of State and Boards of Election officials for repeatedly keeping citizen-proposed laws and charters off the ballot even after procedural requirements, such as the necessary number of signatures, had been met.

“We need to examine how our ballots are being censored,” said CELDF organizer Tish O’Dell in an October 2020 press release. “These plaintiffs are not alone — Missouri, Massachusetts, Arizona, Oregon — constraints on the scope of elections is a national phenomenon.”

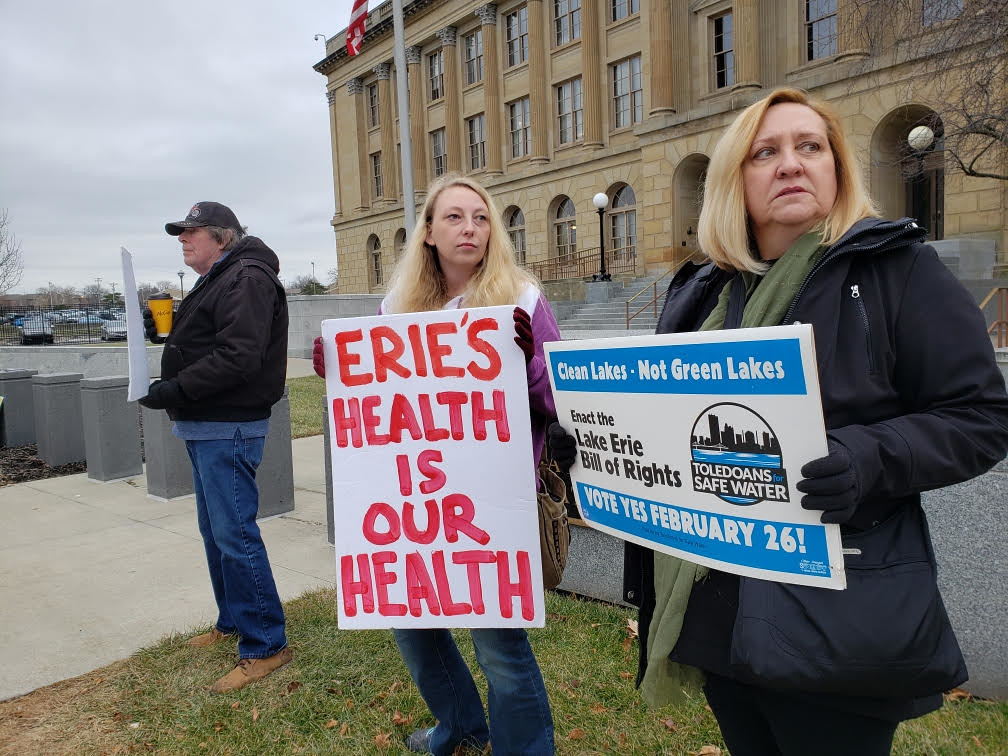

caption: Tish O’Dell (right) of CELDF and Markie Miller (middle) of Toledoans for Safe Water, stand in support of the Lake Erie Bill of Rights in Toledo, Ohio — a Rights of Nature initiative. © Toledoans for Safe Water

On December 1, 2020, the American Petroleum Institute (API), the largest U.S. trade association for the oil and gas industry, filed a brief in opposition to the CELDF suit, a move that reveals the industry’s interest in preventing communities from enacting local laws to protect themselves.

The brief states that API is deeply concerned about the lawsuit because the initiatives that plaintiffs have sought to place on the ballots “include limitations or outright bans on many of the lawful activities” that it either participates in or supports. It goes on to say that if the initiative is upheld, the industry “will suffer serious, immediate, and substantial effects.”

For Markie Miller, an organizer with Toledoans For Safe Water, facing backlash from industry organizations in the heartland state is the norm. Miller was one of the activists involved in passing the landmark Lake Erie Bill of Rights (LEBOR), a municipal law that used Rights of Nature to protect Lake Erie and the surrounding ecosystem after Toledo’s water was poisoned due to complications from agricultural runoff.

caption: Markie Miller in Maumee Bay State Park in Oregon, Ohio (outside of Toledo). Maumee Bay is located in the western part of Lake Erie. Miller, a lead organizer and spokesperson for Toledoans for Safe Water â a grassroots citizens group in Toledo â played a crucial role in drafting, petitioning, and eventually passing the Lake Erie Bill of Rights (LEBOR). Miller and Tish O’Dell’s efforts to pass LEBOR are featured in Pubic Herald’s 2020 award-winning documentary INVISIBLE HAND, with Executive Producer Mark Ruffalo. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Miller’s work with LEBOR began years ago, but action by Toledoans for Safe Water in August 2018 garnered a new response — 14 corporate lobbyist groups filed amicus briefs in a lawsuit Toledoans for Safe Water brought to have LEBOR put to a public vote. These groups included the Ohio Chamber of Commerce, the American Petroleum Institute, and the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation.

Two weeks before the public voted on LEBOR, negative ads began appearing all around Toledo. Anti-LEBOR radio ads played every half hour on multiple local stations, and letters were sent around town calling those involved with Toledoans for Safe Water “outsiders” bent on destroying the community, said Miller.

caption: Markie Miller in Middleground Park along the Maumee River, with downtown Toledo in the background. Miller, a lead organizer and spokesperson for Toledoans for Safe Water – a grassroots citizens group in Toledo – played a crucial role in drafting, petitioning, and eventually passing the Lake Erie Bill of Rights (LEBOR). © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

“We weren’t out there trying to scare people, we were trying to empower people,” said Miller. “[The ads] went the other way. They were going to frighten you into voting ‘No.’”

Miller says some people were intimidated by the ads, worrying that they would kill LEBOR’s chances, but she felt validated.

“We’re a threat,” said Miller. “Some big player out there does not want this to succeed.”

LEBOR passed on February 26, 2019. The post-election campaign finance reports showed BP Corporation contributed $302,000 to the anti-LEBOR campaign by funding an organization called Toledo Jobs and Growth Coalition.

Toledoans for Safe Water spent less than $6,000.

Immediately after LEBOR passed by majority vote, Big Ag sued and the rights-based law was ruled unconstitutional in February 2020. The ruling represents a larger trend in cases regarding community rights and fracking bans in Ohio – local democratic movements across the state are suppressed as corporate interests like Big Ag and Big Oil take control. For activists like Beiersdorfer, the path to democractic control is long and full of failures.

“We don’t have any illusion that we’re going to win immediately and it’s going to change everything,” said Beiersdorfer. “This is a marathon, not a sprint.”

caption: Susie Beiersdorfer beside the Mahoning River in Youngstown, Ohio. Location is near the B&O Station Banquet Hall not far from Mill Creek Park. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Establishing local control, or fighting against big government, is something that neither the state nor big business wants — it takes away both power and money.

Andrew Gross, the prior Navy health physicist, said that if Ohio activists want to create actual change, the only road forward is through monetary pressure on the state and the industry. “It’s all about money,” Gross said. “Let’s face it.”

“To me, the only way to do it is to hit them financially through lawsuits, and then to get the guys who have a real financial interest…to start making noise,” Gross said. It takes “pressure on the legislature’s wallets and pressure on the wallets of the guys who are producing [fracking waste].”

Experts Say TENORM is a Health Risk, Communities Try to Start Health Registry

In 2009, Deb Cowden, an M.D. and family medicine specialist outside of Dayton, Ohio, received a card in the mail, asking if she and her husband wanted to lease their land for $35/acre. The couple, whose property included an organic orchard, didn’t think much of the offer, tossing the card in the trash that same day. When their neighbor called them asking for their thoughts on the offer, they reluctantly fished it out of the trash.

“I think we’re going to have to know about this,” Deb’s husband said at the time.

Despite lacking a concrete understanding of the potential exposures to radioactivity, Cowden and her husband began to research the offer, figuring out that Quebec Energy LLC was a Dubai-based company and that the leased land would be used for fracking and fracking waste operations.

What Cowden did not have at that time were studies like an October 2020 paper published in Nature Communications, which found that the radioactivity of airborne particles increases significantly downwind of fracking sites in the U.S. Using data collected from 157 radiation-monitoring stations around the U.S. between 2001 and 2017, Harvard scientists noted a radioactivity rise of 40% compared with background levels in the affected sites.

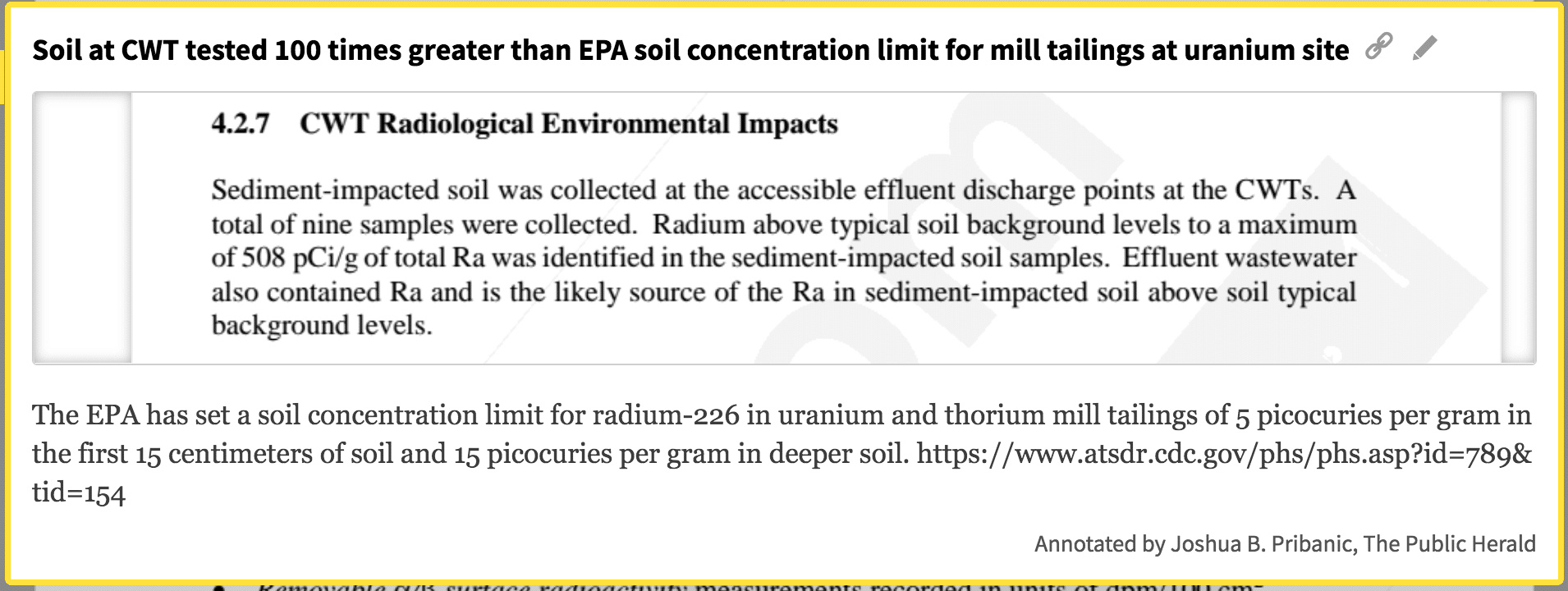

caption: DEP’s 2016 TENORM study (performed by Perma-Fix) found radium in soil 100 times greater than federal regulations, or Ohio’s TENORM code for landfills, at a site treating Marcellus Shale fracking waste. © Public Herald

Cowden quickly realized the potential risks and began traveling the state speaking about the health effects of fracking and how bodies can be affected by the air and water contamination related to fracking.

She found out about the work of the Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project (EHP) and, in 2016, she joined EHP representatives, FracTracker, and Physicians, Scientists, and Engineers for Healthy Energy at a conference in Chicago to discuss health issues associated with fracking. They discussed the creation of health registries to keep track of communities’ health over time, containing contact information of people that live, work, and go to school around fracking and fracking waste sites.

“But, there was no money,” said Cowden. The organizations decided to begin efforts in their own states with the hopes of eventual collaboration across state lines.

Cowden said they had high hopes, thinking a collaboration could lead to a greater understanding of health effects — their data would “talk to each other,” she said.

Cowden returned to Ohio and began a collaboration with Faith Communities Together for a Sustainable Future (FaCT), a religion-based nonprofit working to promote a clean Ohio. Together, they created what is now known as the Ohio Health Project (OHP), traveling the state, training volunteers, and collecting information on those living near fracking operations.

OHP has spent the past few years working slowly — building up the registry, fighting against geography, misinformation, and teaching about the risks of TENORM. But Cowden is optimistic about its progress.

“People are realizing that whether you’re Democrat or Republican… we’re all people,” said Cowden. “We all breathe air, and we all need water.”

caption: George Jarmon, fishing in Glacier Lake in Mill Creek Park in Youngstown, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Cowden isn’t wrong and a growing body of data proves her position. And yet the oil and gas industry consistently claims that the levels of radioactivity in its waste and byproducts are safe, while TENORM mountains pile up across the country. In Ohio, where new rules to govern the risk have been delayed for years and public officials are prone to protect industry instead of the public, communities face a unique challenge — one that doesn’t have partisan interest — one that will last 1,600 years.

Investigative Journalists Joshua Boaz Pribanic, Melissa A. Troutman, Jake Conley and Elijah Labby contributed to this story

Funding for this series was made in part by the Park Foundation