One Year Later: Officials Found Drilling Chemicals in Public Water, But Told No One

One year ago, on September 24, 2015, a new company owned by billionaire Terry Pegula — JKLM Energy — announced that it had contaminated private drinking water supplies while *drilling for natural gas in Potter County, Pennsylvania.

The threat of contamination reaching nearby public water sources forced the shutdown of two public water systems and began what is known as the “North Hollow” investigation.

“Two of four water supplies at Charles Cole Memorial Hospital were removed from service” on September 23rd due to possible impact according to records obtained by Public Herald.

Local officials were swift to note that both public drinking water systems – Coudersport Borough Water Authority and Charles Cole Memorial Hospital – were shut off on September 23 as a “safety precaution” reassuring concerned residents that “no impact” had been detected at those supplies.

On October 27th, The Bradford Era reported that Potter County Commissioner Paul Heimel “hope[d] to clear up ‘erroneous reports’ claiming those [public] water sources were polluted by the spill…”

As of today: at least six treatment systems have been installed on private water supplies in North Hollow, one of the two public water systems is back online, and JKLM is currently drilling new wells less than a mile away from the contamination.

However – the investigation is not over.

Public Herald has uncovered evidence that, from the very beginning, JKLM Energy and DEP officials knew contaminants were detected in public drinking water, but told no one.

In 2015, an October 7th email to JKLM representatives obtained by Public Herald, PA DEP Program Manager Jennifer Means wrote:

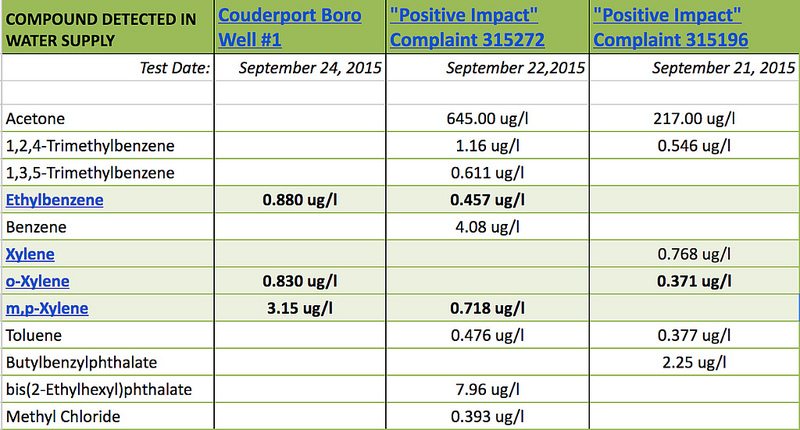

“We…noticed the detects of MBAS and acetone in the hospital spring, and BTEX in Coudersport’s Well 1, but recognize that these water sources have been off-line.”

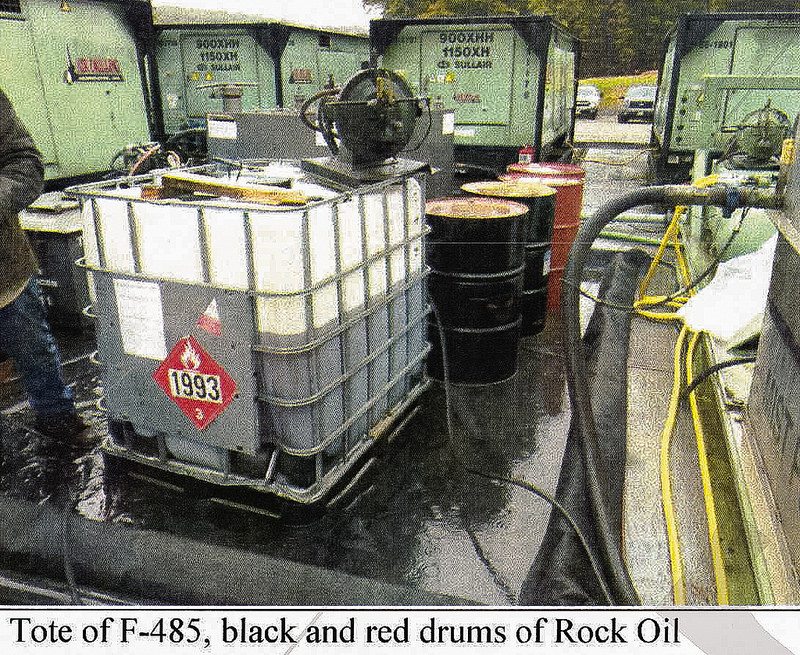

From the start, JKLM referred to the injected “surfactant”— f-485 — as “soap” and told the public that the “primary chemicals of concern” were MBAS (methylene blue activated substances), isopropanol, propanol and acetone. [Read Public Herald’s previous report to find out more about the health implications of f-485.]

On September 29th a JKLM press release concluded by mentioning that the company had begun “investigating” the use of “Rock Oil,” but there was no explanation about why Rock Drill Oil was a concern or what specific chemicals it might contain.

It seemed that not even JKLM knew what JKLM had pumped underground.

Photo from PA DEP inspection report showing chemicals used by JKLM Energy during the contamination of drinking water supplies in Potter County, Pennsylvania.

The company’s September 29th press release included details about tests for five private water supplies and a pond where contaminants surfaced 2.8 miles away from JKLM’s gas well. But it never mentions water tests collected the very same day that showed BTEX in Coudersport’s public water well and MBAS and acetone in the hospital’s spring.

In fact, JKLM made no mention of BTEX in any of their 16 press releases regarding the North Hollow investigation.

It wasn’t until a December public meeting (three months later) that PA DEP revealed, for the first and only time, that BTEX had contaminated private water supplies.

BTEX — benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene — are a group of carcinogenic compounds that can damage human health. The chemicals are often in fluids for fracking, and have been detected at high volumes returning back to the surface as ‘flowback’ — or wastewater — according to studies from US EPA and Environmental Health Perspective (EHP).

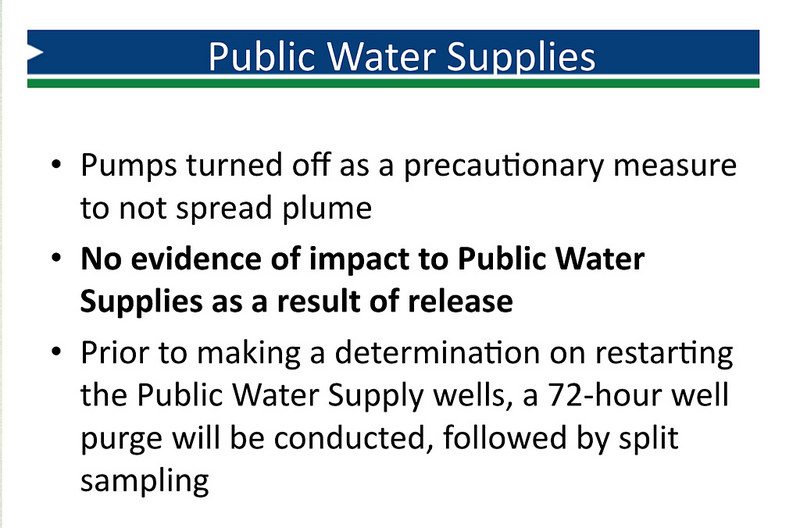

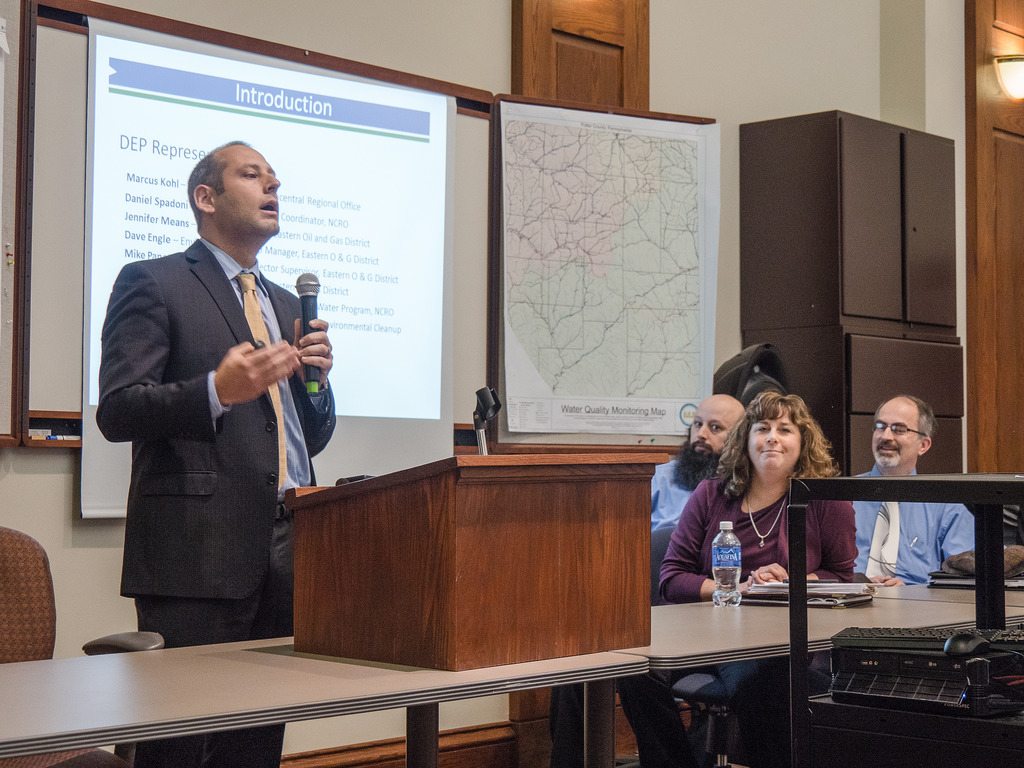

At the December meeting, DEP’s Geologist Bill Kosmer told the public that the agency tested the borough’s well, but “no evidence of impact to public water supplies” existed.

No one at the meeting from DEP mentioned the presence of BTEX in Coudersport’s Well 1 from the September test results.

PA DEP declares no impact to public water supply in Potter County powerpoint presentation despite detection of drilling pollutants in water tests after contamination of groundwater.

DEP’s Community Relations Coordinator, Daniel Spadoni, did not return Public Herald phone calls for this report. Jennifer Means, when reached by phone, stated that policy prevented her from answering questions with media and promptly hung up.

(Updated 9/29/16) Five days after this story published, Spadoni replied to questions from Public Herald that were left on his voicemail over a week ago:

The “hospital spring” is not a water source that is part of the hospital’s public water supply. The sources serving the Cole Memorial Hospital are two groundwater wells (South Well and North Well). The spring where MBAS and acetone were detected is not part of the public water supply system. The public water supply was not impacted.

The reference to BTEX detects in the Coudersport Well 1 refers to very low level detections (less than drinking water standards) of xylenes and ethylbenzene in a sample collected by JKLM on September 24, 2015. The department’s Safe Drinking Water Program, which has regulatory oversight of public water supply systems, sampled this water well on October 6, 2015 and did not detect these compounds. Additionally, the primary constituents of concern: isopropanol, acetone, and MBAS, were not detected in this water well. Therefore, DEP does not believe that this public water supply was impacted as a result of the JKLM release.

The department’s enforcement action regarding this incident is not yet final. Once it is finalized, a news release will be issued.

Spadoni’s statements do not clarify why the Department chose not to notify the public about the BTEX test results at the Coudersport Water Well 1. Public Herald has responded to Spadoni’s email about DEP’s conflicting statements and actions regarding “impact,” levels of BTEX, and to request all water test results for both Coudersport’s and Charles Cole Memorial Hospital’s water sources in order to verify the current status of those supplies.

(Left to right) DEP North Central Regional Director Marcus Kohl introduces the ongoing investigation of September 2015 drinking water contamination by drilling company JKLM Energy in Potter County, Pennsylvania. DEP Geologist Bill Kosmer, Program Manager Jennifer Means, and Environmental Cleanup Manager Randy Farmerie wait to present.

The Public Trust

“Public trust states that the government is a trustee to protect these natural resources — air, water, land…protect them for this generation and for many generations down the line.” ~ Kelsey Juliana on Moyers & Company’s final broadcast

It took state regulators five months to release a statement about the condition of Coudersport’s public water supply. DEP’s brief press release left out specific parameters of which contaminants were detected during its investigation and gave Coudersport the “ok” to resume serving water from Well 1:

“The results of sampling done in late December by DEP and the authority indicate all drinking water parameters are well below maximum contaminant levels or were not detected,” DEP Regional Director Marcus Kohl said. “All other parameters were not detected or at minute safe levels.”

What DEP chose not to report is that BTEX was detected in Coudersport’s public water supply in September at levels two to four times higher than amounts found nearby in private water where DEP determined the water had been impacted by JKLM.

On February 23rd, the day after DEP’s press release, **The Associated Press further obfuscated the issue by inaccurately reporting the amount of chemicals used by JKLM (AP reported 55 gallons; JKLM has reported 98) and choosing to call the chemical solution “soap” without mentioning any further details.

If contaminants associated with JKLM’s chemical release were detected in public water sources – why didn’t state, company, local or hospital officials ever talk about it? If they had, it would have been the first time in the U.S. that a public drinking water supply was contaminated by “trade secret” drilling chemicals meant to be used for fracking.

Whether or not contaminants are currently present in or near any public water source is not the only concern.

The presence of MBAS, acetone, and BTEX presents an even bigger question: If contaminants got their once, how easily could they get there again?

The Perfect Experiment

“What JKLM did was my ideal experiment.”

This is Dr. John Stolz, Director of the Center for Environmental Research and Education at Duquesne University and a member of DEP’s Laboratory Accreditation Advisory Board (LAAC).

“What JKLM injected essentially served as a chemical tracer that showed where and how far contaminants traveled underground. I’d really like to be able to add tracers, before other chemicals are added, to see if pathways exist before fracking begins. But, as a scientist, I’m not allowed to do that.”

To Stolz, the fact that JKLM’s inadvertent “tracer” surfaced nearly three miles away in only a matter of days is alarming.

“That’s huge,” Stolz told Public Herald. “And it’s cause for concern with every new well a company drills in the area.”

“Serious consideration must be given when deciding whether drilling should take place inside of drinking water supply areas,” Stolz added. “Before any drilling happens, a detailed emergency notification plan should be in place and public water suppliers must have alternate water supplies ready to go.”

Protecting The Public Trust

Potter County is governed by three county commissioners – Paul Heimel, Doug Morley and Susan Kefover – who led the aforementioned public meeting in December hosted by the Natural Gas Task Force to inform concerned residents.

At that meeting, public participation was limited to questions written on notecards, then promptly ended after Public Herald pressed JKLM about BTEX and the “detailed chemical analysis” of trade secret drilling fluids that the company refused to make public.

To find out how the county commissioners felt about the drinking water contamination and new drilling by JKLM one year later, reporter Sierra Shamer made several unsuccessful calls to the County Commissioner’s Office but reached Commissioner Heimel on his cell phone.

“It’s not my place to try to make a judgement on the company’s response and whether it was fully compliant, whether it was above and beyond the call of the legal requirements,” Heimel told Shamer. “I’m not in a position to judge it, because I haven’t been directly involved.”

But why wouldn’t a local public official, whose duty is to inform and protect the public trust, not be directly involved addressing the contamination of county drinking water?

Heimel went on: “There are a lot of scientific and technical and legal aspects involved that I wouldn’t be in a position to judge, right?”

But DEP is in the position to judge JKLM. So Shamer asked Heimel, “Do you think [DEP] did their part in the investigation?”

“I would give the same answer,” Heimel replied. “From my very limited perspective, I haven’t seen any glaring examples of any shortcomings.”

But Public Herald has published a laundry list of shortcomings:

- MBAS and acetone were detected at the hospital, but never mentioned

- BTEX was found in Coudersport’s water supply, but never mentioned

- Neither DEP or JKLM notified the public about contaminants in public water supplies

- Residents living in the zone of contamination reported to Public Herald that they’d learned about the incident only weeks later via “word-of-mouth”

- JKLM has still never disclosed the “detailed chemical analysis” it conducted of f-485, a chemical listed on the manufacturer’s website as “fracturing fluid”

- PA DEP has not issued any fines or resolved any penalties, yet have issued 22 new permits to JKLM to drill in Potter County, 10 of those permits for North Hollow

Still, it seems that just the right people dotted and crossed just the right letters of the law so that, at the end of the day, everyone can say – they did everything they (legally) needed to do.

However, doing the bare minimum of what’s considered legal can still leave elected officials open to violations of the Public Trust.

In a landmark public trust decision, Chief Justice Castille of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld the court’s ruling to strike down a statute the Pennsylvania Legislature passed in 2012 to promote fracking which would have banned a community’s right to limit drilling.

As recalled by Mary Christina Wood in an interview with Bill Moyers, a law professor at University of Oregon:

“Chief Justice Castille began his opinion by saying that citizens hold inalienable environmental rights to assure the habitability of their communities.” http://billmoyers.com/episode/full-show-climate-crusade/ (11:00)

Government officials can also be sued for abusing or neglecting their responsibility to protect health and safety. Take for example the case of Redwood City Council (California), where elected officials were forced to pay $4.5 million for environmental cleanup and attorney’s fees regarding the contamination of public waterways.

In Pennsylvania, a person or group can request that the State Supreme Court issue a writ of mandamus to compel a public official, corporation or agency to perform neglected duties.

Potter County Commissioners did not violate the public trust by not knowing the truth, but neither did they do their due diligence to discover what the truth really was. All of the documents in this report were public and obtained through public Right-to-Know Laws.

Perhaps all that local elected officials in Potter County are really guilty of is ignorance.

When Is Water Considered Impacted?

In an email regarding private water supplies, DEP tells JKLM representatives that “just because parameters of interest are not detected at levels greater than a Department standard, does not mean that there was not an impact to the water supply.”

Yet, despite their own definition, DEP never issued a positive determination of impact to the East Well 1 public drinking water supply or the hospital’s spring.

When Public Herald asked for more clarification regarding the public water supplies earlier this year, DEP Press Secretary Neil Shader replied via email, “The department has no further comment at this time.”

Although testing is reportedly ongoing, no full test results have been made public by the Department, JKLM Energy, Charles Cole Memorial Hospital, or the Coudersport Water Authority for public water.

Public Herald made a formal Right-to-Know request via email to Charles Cole Memorial Hospital earlier this month for water quality testing of the hospital’s public water supply. Director of Maintenance and Engineering Melvin Blake responded with a letter from the hospital’s attorney’s denying Public Herald’s request for test results dated September 20, 2016:

“My client [Charles Cole Memorial Hospital] will not consider your request.”

– Elliott J. Ehrenreich, KNOX McLAUGHLIN GORNALL & SENNET, P.C.

Neither Blake nor hospital press contact Dawn Snyder responded to Public Herald’s question about why the hospital public water supply is still offline.

In 2015, Charles Cole Memorial Hospital leased with JKLM Energy to frack for natural gas on hospital property. According to Endeavor News, Cole Memorial Hospital received “an initial payment in excess of $1 million” from the deal.

Federal Agency Begins Public Health Consultation

In North Hollow, JKLM, PA DEP, and the Pennsylvania Department of Health have been aware of residents’ health complaints related to water contamination from JKLM’s operations.

But inside DEP permit records, JKLM stated that one resident “experienced gastrointestinal issues possibly associated with water use…”

In October, another health complaint was reported – a resident who suffered from headaches and stomachaches during the time they noticed their water looked cloudy and brown.

“The DEP was looking at it as an environmental investigation, and no one looked at it from a public health perspective,” said Laurie Barr, a resident who contacted the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) regarding the community health impacts from drinking water contamination in North Hollow.

Shortly after JKLM polluted groundwater, Barr hunted down a list of chemicals used after the company declined to reveal it.

Barr navigated “trade secret” exemptions that allow oil and gas companies to keep chemicals confidential and was forced to hand copy MSDS sheets at the local Emergency Services Department, wherein she discovered that about 85-90% of the chemical solution JKLM used was “proprietary.”

The full chemical composition of the unapproved fluids JKLM Energy pumped underground is still unknown. That’s why Barr contacted ATSDR in February.

“Residents have not had their health related questions answered and received very little information on proprietary chemicals that are in the aquifer,” Barr said. Health concerns have not been mentioned by either DEP or JKLM publicly.

Unlike DEP, the ATSDR conducts an investigation through the lens of public health, typically upon the request of the EPA, state, or an individual citizen, the ATSDR will conduct a public health consultation when warranted.

Similar to North Hollow, ATSDR was called in to investigate water contamination cases in Dimock, Pa. following residents continued concerns. Their conclusions in Dimock turned out to be more alarming than what US EPA or PA DEP led the public to believe.

For North Hollow, they’ve reviewed DEP data published by Public Herald and records from the Department of Health (DOH). ATSDR does not conduct their own water sampling during a consultation.

“We rely on regulatory agencies, and other sources of valid, laboratory, environmental data….Our approach is to include the community, so if there’s others that want to reach out to us and they have data and they want to share it… we’re open.” — Robert Helverson, ATSDR

Residents with information or concerns can contact the ATSDR office:

Robert H. Helverson, MS, Region 3 Representative, Division of Community Health Investigations (DCHI), Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

1650 Arch Street (3HS00)

Philadelphia, PA 19103

(215) 814-3139 (Office)

(215) 814-3003 (Fax)

email: [email protected]

The ATSDR is not a regulatory agency who can hold companies responsible for fines and penalties. It would be up to DEP, EPA or the public’s discretion to act on ATSDR’s conclusions.

So far, the U.S EPA has been “hands off” in the investigation of drinking water contamination in Potter County.

New Drilling Permitted for North Hollow

New JKLM Enerrgy well pad in North Hollow, Potter County, PA. Photo by Sierra Shamer © Public Herald

In December 2015, JKLM personnel reported at a public meeting that, “in view of the geologic characteristics revealed as a result of this incident, JKLM has no plans to drill any wells in that area.”

A few months later, JKLM began applying for new permits to drill in North Hollow.

Since May, DEP has approved ten new permits for JKLM to drill in North Hollow, despite the agency’s ongoing investigation, and 12 new permits for other areas of Potter County. PA DEP has issued four violations to JKLM, but all violations remain unresolved and no fines are yet levied.

JKLM drilled four of new wells at “Reese Hollow 117” in July, and just started drilling the remaining six permitted wells on “Reese Hollow 115” this past Thursday.

The proximity of the company’s new wells to several water sources contaminated during drilling in September 2015 is making some residents nervous.

Bob Long lives in North Hollow and shared with Public Herald the health problems he experienced after JKLM’s contamination of local water wells which, he says, the hospital attributed to bacteria.

Long is not convinced that new drilling in North Hollow is without risk. “As much land as there is in Potter County, why would you drill that close to pristine trout waters, headwaters…it doesn’t make a lot of sense.

“Do we really believe that we can go miles under the earth and frack the wells with no consequence? I don’t believe anyone is that naive.”

Read section 6 of the 2002 bio-terrorism act. An interesting read when public drinking or waste water systems are affected.