“Screwed & Glued” – Trading Freedom For Clean Water When Regulators Walk Away

In September 2013, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) received six phone calls from residents in Lenox Township, Susquehanna County who feared pollution of their drinking water. The residents’ attorney had just alerted them to arsenic contamination at a nearby natural gas fracking site.

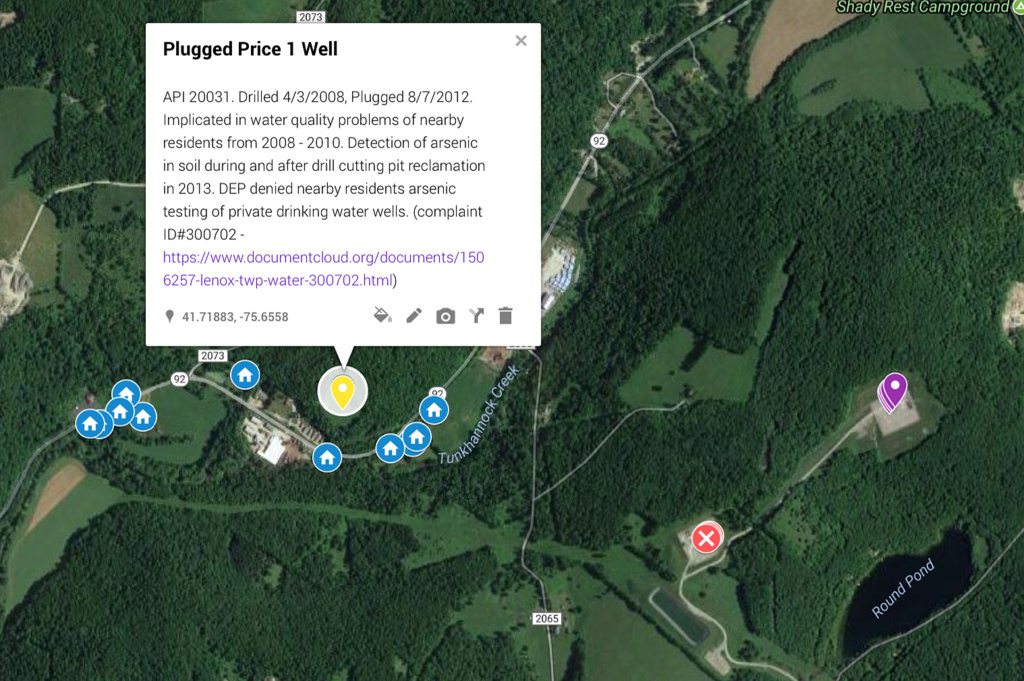

Those calls were grouped by DEP into one complaint file — complaint #300702 — with Inspector Michael O’Donnell and Supervisor Marc Cooley assigned to the case.

Just days later, Supervisor Cooley would deny the residents’ request for water testing.

According to records obtained by Public Herald through Right-to-Know, by the time the calls were made to DEP, Supervisor Cooley had been watching an arsenic problem unfold for months.

Southwestern Energy, an oil and gas drilling company from Houston, Texas had buried drilling waste at their “Price 1V” well pad less than 2,000 feet from residents’ homes. Southwestern removed the waste pit in June 2013, at landowner Ordie Price’s request, but contaminants – including high levels of arsenic, manganese, and thallium – remained.

Drilling waste contains dirt and rock that comes up from oil and gas wells, exposing concentrated heavy metals, like arsenic and manganese, as well as naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM) to the surface through the extraction process.

When Southwestern tried to tell the Department that arsenic at the Price 1V was “naturally-occurring,” DEP firmly disagreed.

Less than two weeks before residents called for water tests, Cooley sent an email to Southwestern outlining the company’s inadequate testing and inaccurate conclusions regarding arsenic in the soil at Price 1V. His email stated that an analysis used by Southwestern’s hired firm, Groundwater & Environmental Services (GES), was “not compatible with the Department’s Statewide Health Standards.”

Cooley also wrote that “soil background was incorrectly determined” and “the conclusion that groundwater has not been impacted in a more immediate vicinity of the [waste] pit cannot be reasonably drawn.”

Only ten days passed between Cooley’s email to Southwestern about the arsenic problem and neighbors’ calls to DEP requesting water testing.

According to the state’s records, the company’s firm encountered an underground “seep” and water had to be vacuumed out of the pit during its excavation.

Still, with this knowledge, Cooley denied all requests for water testing, citing an investigation conducted at residents’ homes three years prior.

Residents first reported water problems to DEP in 2008, shortly after the Price 1 Well was drilled, and again in 2010 after their pipes clogged, flooding their homes, and their water turned “milky black.”

“The water was so black you couldn’t even see through it,” one resident recounted to Public Herald. “Our water was good before.”

DEP sampled residents’ water in 2008 and 2010, but not for arsenic. DEP’s limited testing did, however, find methane and other heavy metals above Department standards.

But after seven months of waiting for DEP to reveal what was in their water, only two out of six residents received “positive determinations” from DEP linking their water pollution to Southwestern’s well operations – complaints #258959 and #258960. The other households, who reported water problems at the same exact time, received “negative determination” letters. According to DEP, their water problems “appear[ed] to be related to background conditions” and therefore not related to oil or gas operations.

Meanwhile, Southwestern’s waste pit was sitting – buried – nearby at Price 1V.

After DEP washed its hands of the issue, residents banded together and sued Southwestern for polluting their water. Ending a seven-year legal battle, residents’ settled for a meager sum in 2015. To get the money, Southwestern required each plaintiff to sign what has become an industry standard in oil and gas areas across the U.S. – the “non-disclosure agreement” (NDA) – whereby signing, residents trade money for their freedom of speech, agreeing never to talk about their water problems and the company again. (NDA’s are often referred to as “gag orders” by residents.)

For this report, the identities of gagged residents who spoke with Public Herald anonymously have been protected.

“DEP dropped us like a hot potato,” said one Lenox Township resident. Another recounted how “DEP just washed their hands of it.”

“The whole DEP, they just sloughed us off,” another resident said. “In other words – there was nothing wrong with your water, it all came from background conditions.”

When Public Herald asked for clarification about the Department’s 2013 refusal to test drinking water in Lenox Township, DEP Press Secretary responded:

“The complainants did not describe any new change in their water since the Department’s previous investigations, so no new investigation was warranted.”

By DEP’s logic, residents need to see, smell, or taste something different with the water in order for the state to justify testing.

But, there’s one big problem with that, says Dr. John Stolz, a Director of Duquesne University’s Center for Environmental Research and Education who has tested residential water wells near oil and gas operations for over a decade. Dr. Stolz also served on DEP’s Laboratory Accreditation Advisory Committee, which addresses quality assurance and quality control issues in the Department’s water testing procedures.

“Typically, the complaints that happen are ones in which there’s a visible change — it’s either color, smell or taste. And it’s because of the constituents that do that: high iron, high manganese, sulfide, or something tastes saltier. But, they could be drinking water that’s laced with arsenic and have no idea it’s laced with arsenic, because arsenic has no taste, color or smell.”

DEP Supervisor Marc Cooley did more than refuse to test in 2013, citing the previous investigation that did not include arsenic testing. He also diverted residents’ complaints to a different fracking site.

Instead of assigning the residents’ complaints to the Price 1V, where he knew arsenic was a problem, Public Herald’s investigation has found that Cooley assigned them to a different well site further away – the Valentine Price North.

This allowed Cooley to deny the water tests by citing 1) a further distance, and 2) the lack of any recent “activity” at the Valentine Price well.

By attaching drinking water tests to the Valentine Price North site, Cooley placed the residents outside of “presumptive distance” – the area around a well site where the company is assumed to be responsible for impacts to drinking water.

“[The] distance and time to nearest gas well drilling negates possibility of presumption…” Cooley wrote.

Explaining the switch, DEP Press Secretary Neil Shader stated in an email to Public Herald that “the Valentine Price North was mentioned in the [complaint] report,” instead of the closer Price 1V, “because [Valentine Price] had the most recent activity.”

But the Valentine well was neither the one DEP had just cited for arsenic problems, nor the nearest gas well to residents’ homes.

When asked why the Department, during a more recent case in Potter County, offered all residents water testing regardless of distance from the source of contamination, Shader had this to say (emphasis added):

“In contrast to [Lenox], in September of 2015 DEP was aware of an actual pollution event occurring as a result of JKLM’s activity in Potter County. We make every effort to be thorough and err on the side of caution in evaluating any potential impact from such incidents. Therefore, the Department collected samples in response to all complaints received, as well as requiring extensive monitoring and remediation efforts by JKLM.”

But DEP failed to “make every effort” in Lenox Township, where the agency “was aware of an actual pollution” of nearby soils and had not yet confirmed there was no impact to groundwater. Additional testing of nearby water wells in Lenox could only have helped DEP “err on the side of caution.”

Instead, DEP’s denial of water tests to families who feared for their safety errs on the side of misconduct at the expense of human health.

Public Herald has analyzed over 1,000 citizen complaint investigations and found DEP misconduct in over 175 cases. Many of them mimic the same patterns DEP displays in the Lenox Township case – altering or ignoring data, denying water sampling, letting residents wait months or years without answers about their drinking water, and only holding companies responsible for some water contamination, but not all.

More than unjust, this is also against state law, which obligates DEP to hold companies accountable for contaminating drinking water.

DEP’s malfeasance was on full display in Westmoreland County when a waste pond leaked and contaminated several water supplies. After its investigation, DEP blamed the waste for some of the impacted water supplies, but not all.

In a letter to DEP in 2014, attorney Nick Kennedy at Mountain Watershed Association insisted the Department reexamine its decision:

“The Department stated it was unable to conclude that oil and gas activities impacted the [redacted] water supply….A comparison of the water test results of [redacted] and their next door neighbors…demonstrates that the two neighbors suffered the exact same impacts from the leaking impoundment of the Kalp #1-9H site in Donegal Township.”

After DEP manipulated its way out of dealing with the water problems in Lenox Township, 13 families with 10 children were forced to file a civil action lawsuit against Southwestern demanding a jury trial and damages, including a “medical monitoring trust fund” for the “early detection” of “latent disease” caused by exposure to “hazardous substances.”

According to confidential sources, each homeowner received around $21,000. Tenants received more like $1,000, which didn’t cover the costs of years of buying bottled water. After the gag order settlement was signed for this meager sum, a few who left the table would blame the “worthless” attorney who handled the case.

To this day, there are residents who still cannot use their water for drinking or cooking.

No one knows how many families living in the natural gas fields of the United States have traded their freedom of speech for money over contaminated water. The number is likely hundreds, possibly more.

But this is the point of non-disclosure agreements – to silence the truth and hide evidence about the real impacts of natural gas development on drinking water supplies.

However, at least one legislator, Representative Chris Rabb (D) in Philadelphia, wants to shed some light.

Newly elected in 2017, Rabb is working on an amendment to the Pennsylvania Oil & Gas Act to include “Community and Public Resources Impact Reporting” which would require operators to annually disclose “the number of nondisclosure agreements the well operator has signed with individuals who claimed that the operations have harmed their health or contaminated their drinking water or otherwise damaged their property.”

As Public Herald reported in October 2017, Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro’s office has received hundreds of complaints about water contamination, regulatory failure, and other violations related to oil and gas development since taking office in January 2017.

Last summer, agents from Shapiro’s office visited the homes of families across the state who recounted stories of water contamination, illness, animal deaths, and more that they claim have been caused by fracking.

But the homes in Lenox Township were not among the ones visited by the Attorney General’s agents. One resident told Public Herald that s/he chose not to contact the Attorney General so they could “just move on with life.”

According to DEP, and nearly every faction of PA government, the problem of water contamination related to fracking is minimal and under control. But unearthed data published by Public Herald in 2015 and 2017 has repeatedly shown that DEP is unable to abate water contamination and does not hold companies fully accountable. And before he was elected Attorney General, then-candidate Josh Shapiro already knew it, too.

Two years ago, during his campaign to become Pennsylvania Attorney General, Josh Shapiro wrote an editorial about “Protecting Pennsylvania’s Drinking Water” that targeted water pollution from oil and gas development. In it, he asks:

“Why isn’t state government doing more to fight for those families? Why isn’t our government standing up to the companies that pollute our environment and harm public health and holding them accountable? If I’m elected attorney general, I will.”

After a year in office, and exposure to an unprecedented call-to-action from residents about DEP conduct, Shapiro has yet to mention the issue again since taking his oath on January 21st, 2017.

In his editorial, Shapiro was very specific about how he would hold “frackers” accountable:

“I will elevate and empower the Attorney General’s Environmental Crimes Unit…devote resources to strengthen this unit’s ability…use civil investigative demands and civil subpoenas to investigate companies of concern…launch a special task force of district attorneys from the counties most affected by fracking to share information, determine patterns of abuse and coordinate enforcement strategies…pursue criminal cases against frackers as well as settlements that are more than a slap on the wrist…Because young children, the elderly and those with weakened immune systems are most vulnerable to the dangerous effects of fracking, violations that occur close to these populations should warrant tougher penalties.”

He goes on:

“In Pennsylvania, we need an attorney general with the will to enforce state law, prosecute frackers and other polluters and ensure clean air and water for every Pennsylvania citizen. Clean air and pure water is our constitutional right, and I’ll fight to protect that right for you.”

Instead of addressing water contamination, or DEP negligence, Shapiro has taken another road, one originally paved by former attorney general Kathleen Kane, by prosecuting oil and gas companies for cheating landowner’s out of royalty payments.

On December 22, 2017 Shapiro tweeted, “We sued the frackers…we’re committed to getting landowners the money they’re owed.”

After the environmental group PennEnvironment thanked him for suing the U.S. EPA about air pollution controls, Shapiro tweeted, “Pennsylvanians have a state constitutional right to “clean air, pure water” (Art. I, Sec. 27) and it’s my job to protect the rights of all in PA.”

Almost a year has passed since Public Herald’s body of evidence about regulatory failures hit Shapiro’s desk, yet there’s been no comment or official statement from his office – only silence.

Meanwhile, the non-disclosure agreements continue as water contamination and legal battles from shale gas development persist.

For Lenox Township, as one resident put it, the state and industry have left them “screwed and glued.”

thank you for all you are doing….

When did Josh Shapiro say he would prosecute the DEP? Well, never. Did the DEP engage in heavy duty industrial practices in a slipshod way? Not really. Can we leave the blame lie where it lays and just get on with it? The AG will not sue the DEP and subject the state to liability. It’s time for another plan other than Pennsylvania suing Pennsylvania.