Investigation Uncovers Ohio Is “Illegally” Building Radioactive Mountains, Affecting 26 Waterways

Investigation Uncovers Ohio Is “Illegally” Building Radioactive Mountains, Affecting 26 Waterways

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

SUPPORT newsCOUP

Public Herald is a nonprofit newsroom that holds those in power accountable. You can receive our latest breaking stories by subscribing to our newsletter or becoming a Public Herald Patron.

by Talia Wiener for Public Herald, From Editors Joshua Boaz Pribanic and Melissa A. Troutman

July 31, 2021 | Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers, TENORM Mountains

Part 2 of Ohio TENORM Mountains 3-part series. Read Part 1. Get the story in print through one of seven Ohio Ogden papers, starting front-page at Sandusky Register. Contributions to this series were made by Sandusky Register Editor Matt Westerhold and Journalist Tom Jackson.

Lynn Anderson spent her teen years exploring a piece of land that sat right on the border between Ohio and Pennsylvania. She rode her horse through the winding trails, swam in the quarry, and watched critters congregate around the lakes.

“We used to swim in the quarry lake. I would ride my horse down there. there were nice switchback trails, trees, all kinds of waterfowl and critters,” said Anderson, remembering back to 1972. “You could ride your horse for miles down inside the quarry.”

Since 1894, that land had been owned and operated by Carbon Limestone Company, which became one of the largest limestone producers in Ohio. But by 1972, when Anderson was 15, all the limestone had been extracted and she roamed the uneven land freely.

25 years later, Anderson returned to her old stomping grounds in eastern Ohio, hoping to again walk the trails and dip a toe in the water. But a surprise awaited her — the land had been transformed.

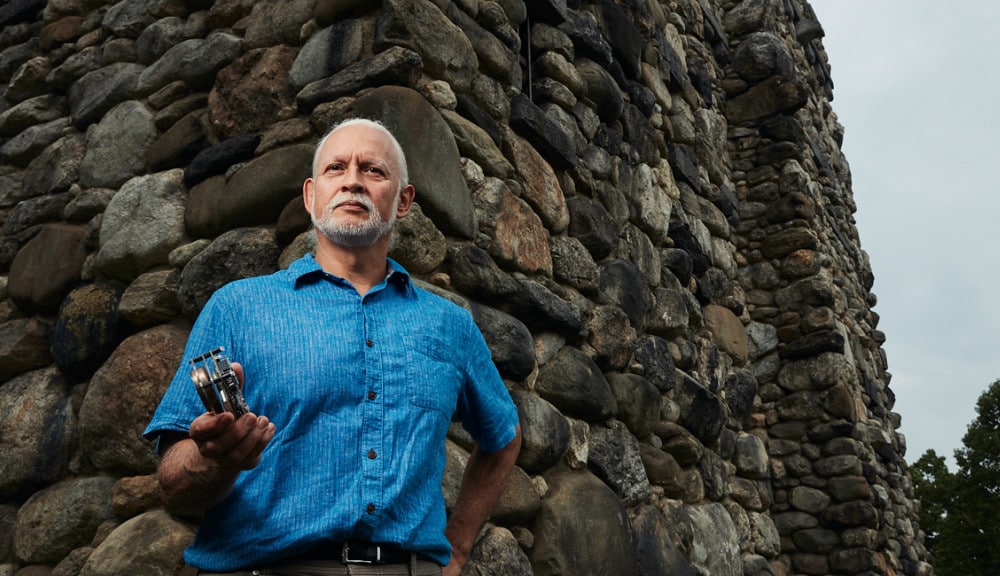

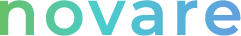

caption: Lynn Anderson at Republic Services Carbon Limestone Sanitary Landfill at 8100 South Stateline Road in Lowellville, Ohio. One of eight landfills in Ohio identified by Public Herald that are storing TENORM waste from fracking — a radioactive byproduct of oil and gas drilling. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

“There was flat land as far as you could see. It was totally filled. It was called BFI. There was a guard shack on one side. You couldn’t get in it,” said Anderson. “I could not believe we had that much (trash) that we filled up that much area hauling in crap.”

She blames state officials — including a former governor and our current governor — for failing to protect the environment.

“There’s Kasich and it’s DeWine. … they know that we have brownfields that have never been cleaned up from the steel mills.”

That failure has caused “tons of cancer” in communities in Ohio, according to Anderson.

No one was allowed onto the property, which was guarded by security. The quarry land was purchased by Browning Ferris Industries in 1995, then sold to BFI, then to Allied Waste who then merged with Republic Services. It’s known today as the Republic Services Carbon Limestone Landfill. In 2019, the landfill received over 1.3 million tons of waste — including radioactive fracking waste.

America is Building TENORM Mountains — In Ohio, That’s Illegal

Never before in the history of America has the country undertaken an experiment like what’s happening with radioactive material from oil and gas fracking.

Everyone knows that oil and gas wells produce oil and natural gas. But few people understand that these wells also produce radioactive waste, or that it’s being disposed of in communities alongside household trash.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines the radioactive portion of this waste as TENORM (technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material), and in communities across shale plays like Ohio, TENORM is piling up alongside watersheds.

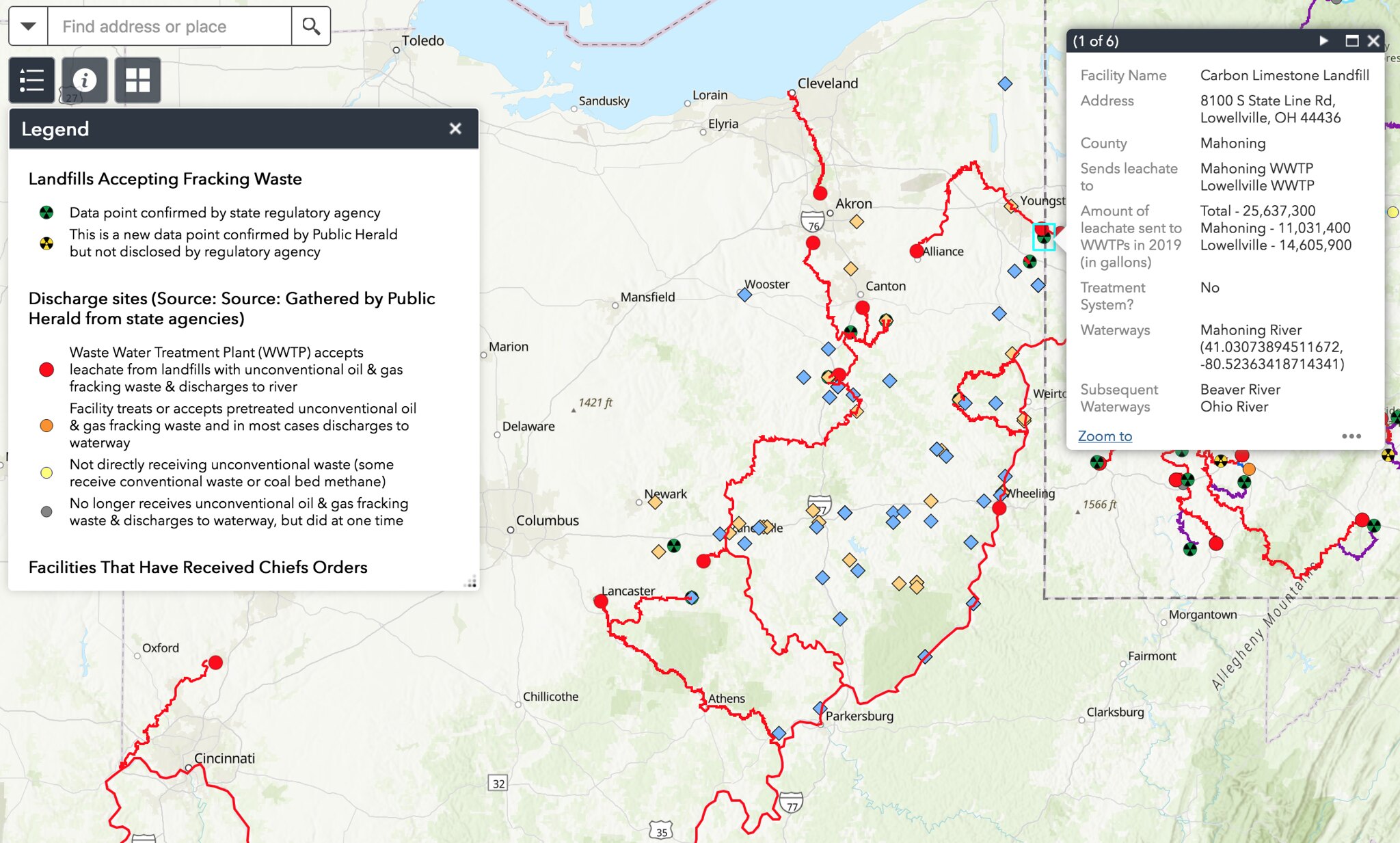

caption: Public Herald’s Ohio TENORM map the identifies eight landfills accepting radioactive fracking waste (trefoil symbols), POTWs who are treating the landfill’s radioactive leachate (red dots), and the waterways affected by the POTW NPDES permits (red lines). Chiefs Orders facilities that are operating or no longer operating (yellow and blue diamonds) are also identified. © Novare Collective for Public Herald

Republic Services Carbon Limestone Landfill is one of the eight landfills in Ohio currently receiving waste from unconventional oil and gas operations, according to information acquired by Public Herald from the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA).

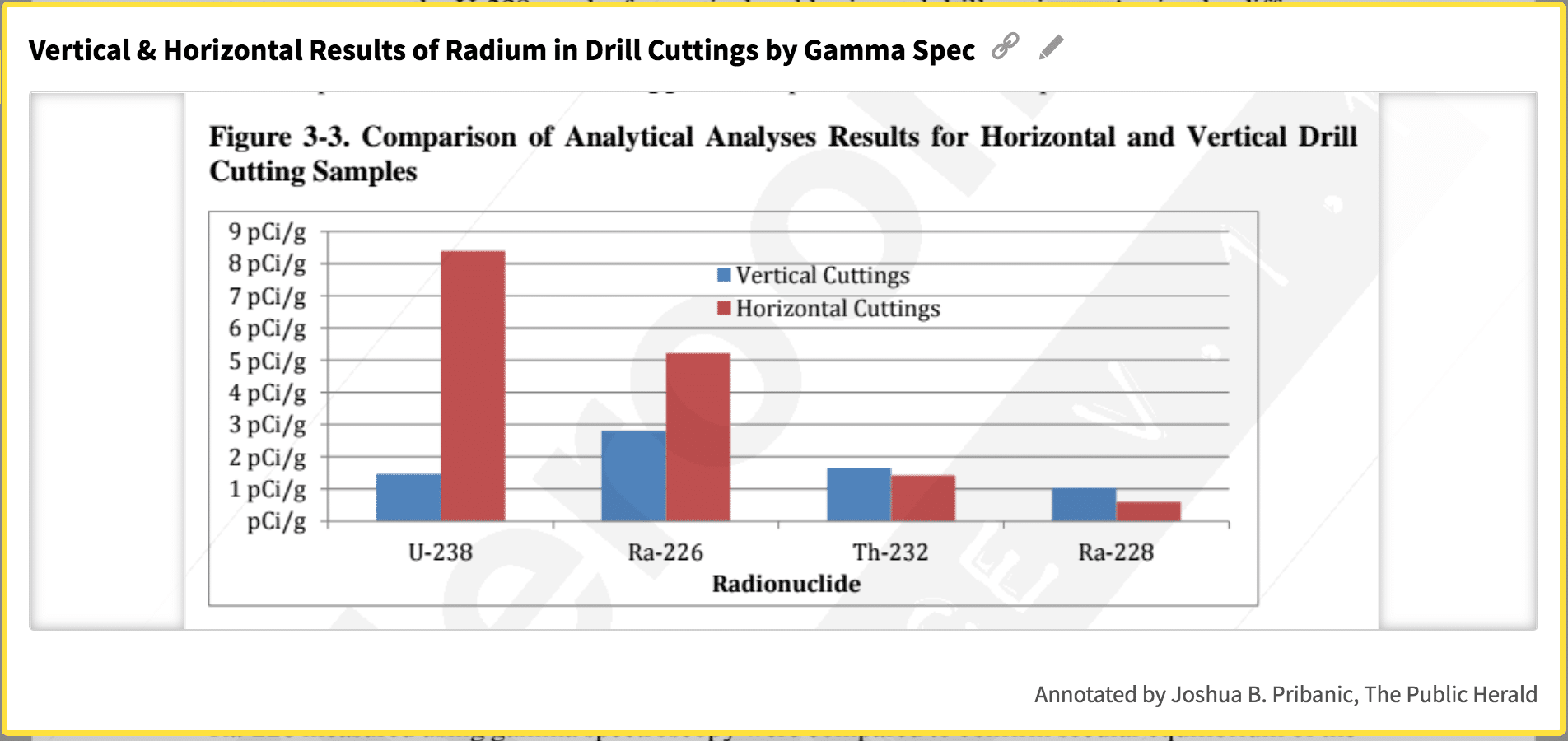

In Ohio, TENORM disposal at landfills falls under O.R.C. 3734.02, which states that a solid waste facility can not accept or transfer TENORM if it contains radium-226, radium-228, or any combination of the two at more than 5 picocuries per gram (pCi/g) over the natural background.

It’s worth repeating that this code puts the limit of TENORM coming into or out of landfills at 5 pCi/g.

Not much testing has been done on TENORM waste in Ohio, but much of the TENORM waste arriving at Ohio landfills is from the Marcellus Shale — the same shale waste that has been tested in a 2016 Pennsylvania TENORM study. In that study, radium levels from fracking waste in the Marcellus were detected as high as 13 pCi/g, more than 2.5 times greater than the Ohio code permits.

caption: DEP’s 2016 TENORM where vertical and horizontal drill cuttings from the Marcellus Shale, the same shale waste being dumped in Ohio, showed levels of radionuclides exceeding federal regulations, mainly radium. (part of the decay chain of uranium and thorium). The graph here shows the average totals using gamma spectroscopy, a way of testing that accurately detects radium, unlike gamma devices used at Ohio landfills to monitor for radium. © Public Herald

The average load for combined radium reported in the study from 18 samples was 5.847 pCi/g, again exceeding the Ohio code of 5 pCi/g.

But even though Ohio’s TENORM code places a strict standard on radioactive waste disposal, the state hasn’t produced documentation to Public Herald of measurement and enforcement for radium at landfills.

“It is an extremely, overwhelmingly strong bet that the waste and disposal practices in Ohio are seeing a great deal of material that exceeds the limits,” said Ohio attorney Terry Lodge. “The state is acting illegally.”

When Ohio EPA (OHEPA) responded to Public Herald’s request for comment about the problems with TENORM, they sent the following statement:

“No landfill in Ohio has authorization to accept TENORM above five picocuries per gram above natural background. As such, Ohio regulations are set to manage TENORM at the source. We believe this is an effective approach for protecting public health and the environment.”

OHEPA also asserted that TENORM regulation is the Ohio Department of Health’s (ODH) responsibility. The Ohio Department of Health has published a briefing document on TENORM regulations in Ohio that states:

“Solid waste landfills can only accept TENORM wastes for disposal at concentrations less than 5 picocuries per gram above natural background.” However, “If a solid waste landfill or other facility wants to dilute TENORM wastes with concentrations greater than or equal to 5 picocuries per gram above natural background prior to disposal, this activity requires authorization from the Ohio Department of Health.”

In the event that “solid wastes cannot be managed at a solid waste landfill because of elevated levels of TENORM, the waste must be sent to a low-level radioactive waste disposal facility,” according to the Department of Health.

Public Herald was unable to verify the statements from OHEPA and ODH since neither agency provided statewide documentation of drill cutting test results using gamma spectroscopy to negate the levels of radium detected in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale TENORM study.

Public Herald sent requests for comment on the probable code violations to the offices of Ohio Attorney General Dave Jost and Ohio Governor Mike DeWine. Neither office replied to the requests before Public Herald’s print deadline.

While the two states share the same shale plays for fracked gas — the Marcellus and Utica formations — Public Herald has found Pennsylvania’s TENORM regulations are much weaker than Ohio’s, while both states inadequately enforce or measure for TENORM. If Pennsylvania landfills shared the same law as Ohio for TENORM waste, they would operate illegally.

How Radioactive Rainwater Is Getting Into Waterways

According to data from Pennsylvania’s 2016 TENORM study, landfills accepting “residual waste” in the form of unconventional drilling solids from the Marcellus shale are receiving loads of TENORM — mainly in the form of radionuclides radium-226 and radium-228 — at levels that would exceed Ohio’s TENORM code of 5 pCi/g.

DEP data says over 4.8 million gallons of Pennsylvania’s oil and gas well waste was sent to Ohio waste facilities in 2020.

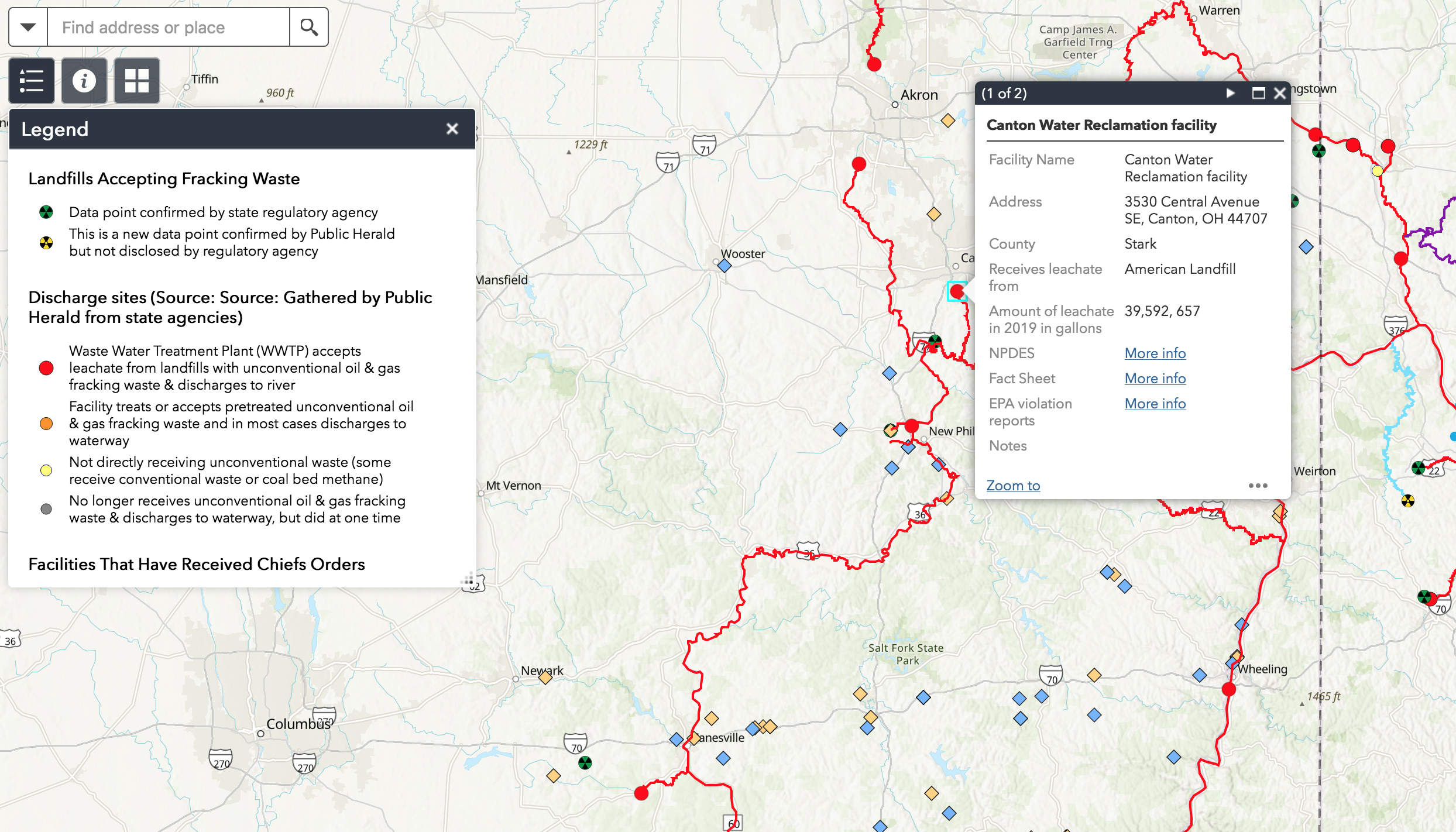

caption: American Landfill in Stark County produces large volumes of leachate from radioactive waste, sending it to Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTW) that discharge in Ohio River and Lake Erie tributaries. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

When rain falls on landfills, water passes through the collected waste and carries (or leaches) some water-soluble contaminants out of the landfill with it. The resulting liquid is contained and stored as leachate.

Oil and gas TENORM waste enters landfills in the form of drill cuttings, pipe scale, produced waters, flowback water, sludge, filtration sleeve (filter socks), and contaminated equipment. According to the industry itself, every part involves radioactivity. A 1982 report commissioned by American Petroleum Institute stated: “[a]lmost all materials of interest and use to the petroleum industry contain measurable quantities of radionuclides that reside finally in processing equipment, product streams, or waste.”

Since radionuclides from oil and gas waste are water-soluble, when it rains at the landfill, they pass into the leachate. From landfills, leachate is taken to a variety of places: like wastewater treatment plants where it then gets discharged into waterways, injection wells where it is shot underground to possibly leak and contaminate water systems, or processing facilities that repurpose it into commercially available products such as salt used to treat at-home pools.

In 2019, Public Herald found Ohio’s eight landfills accepting fracking waste generated over 175 million gallons of leachate. All of it would have contained TENORM, according to experts like Dr. Marco Kaltofen, a nuclear-forensics scientist at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

“We have a fixed amount of radioactivity,” said Kaltofen. “We’re moving it from one part of the environment to another without really dealing with it.”

According to information provided by the OEPA, the leachate from frack waste landfills would be sent to 13 wastewater treatment plants, ten of which are located in Ohio.

The Youngstown Waste Water Treatment Plant, one of 13 in Ohio handling leachate from radioactive waste, at 725 Poland Avenue, Youngstown, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Dr. Kaltofen says that while these treatment plants are able to treat biological materials, they are unfit to deal with radioactive materials. As the waste moves through the treatment plant and into waterways, the level of radioactivity remains the same. Mixing the waste with water may actually allow the radium to accumulate in sediment and more easily move downstream.

26 Ohio waterways are possibly impacted by discharge from the Ohio facilities receiving fracking waste, as well as two additional waterways in nearby states, according to information provided by the OEPA.

caption: Public Herald’s Ohio TENORM map showcases 26 waterways (red lines) impacted by radioactive leachate treatment, stretching from Cleveland, south to the Ohio River. Eight landfills accepting radioactive fracking waste (trefoil symbols) are identified, long with POTWs who are treating the landfill’s radioactive leachate (red dots), and the waterways impacted by the POTW NPDES permits (red lines). Chiefs Orders facilities that are operating or no longer operating (yellow and blue diamonds) are also identified. © Novare Collective for Public Herald

In Pennsylvania’s 2016 TENORM study, soil samples from the discharge points of 9 centralized waste treatment sites (CWTs), where processed fracking waste is discharged, contained radium concentrations of up to 508 pCi/g, over 100 times the EPA’s stated limit at the federal level. The TENORM study concluded, “Effluent wastewater also contained [radium] and is the likely source of the [radium] sediment-impacted soil.”

“Sewage treatment plants aren’t treatment systems for radium, they are transit systems,” said Kaltofen.

caption: Dr. Marco Kaltofen. © Worcester Polytechnic Institute

After filtering through all their waste, Ohio wastewater treatment plants can produce their own leftover sludge. When the waste they are processing is made up of radioactive fracking waste, that sludge contains an even more concentrated level of radioactivity, said Kaltofen.

In Ohio, WWTPs are required to annually report the weight of sludge transferred to other facilities for final disposal. In 2019, eight WWTPs that receive fracking waste from landfills took over 7,000 tons of sludge to disposal facilities around Ohio, according to information from the OHEPA.

caption: Dover Wastewater Treatment Plant, one of 13 in Ohio handling leachate from radioactive fracking waste, at 100 North Tuscarawas Avenue, in Dover, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

WWTPs in Ohio are required to submit reports to the OHEPA that include the volume of the leachate they receive, but they are not required to report the makeup of that leachate. The public has no way of knowing the levels of radioactivity moving through the plants. Confirmed by the agency’s Media Relations Manager James Lee, these reports “do not detail chemical composition/constituents of the leachate received.”

How Much Radioactive Leachate is Entering Ohio Waters?

Alliance wastewater treatment plant in Stark County, OH, received the most leachate of any WWTP in Ohio in 2019, totaling 59,057,529 gallons. This leachate arrived from four different landfills across the state and was released, in accordance with a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit from the OHEPA, into Beech Creek (at Berlin Reservoir), continuing downstream into the Ohio River.

caption: Truck entering Republic Services Carbon Limestone Sanitary Landfill at 8100 South Stateline Road in Lowellville, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

“We have a paper trail like you wouldn’t believe,” said Anderson. “But nothing is being done and nothing is ever done.”

Dr. Kaltofen, and experts who’ve spoken with Public Herald, point out that there’s a failure to require testing to determine the amount of radioactive material in the waste which leaves communities uninformed and in possible danger.

“It’s like if you went to the pharmacy and they said, ‘Here are ten pills and they weigh 11.47 grams, but we’re not going to tell you their chemical composition, just take them,’” said Kaltofen. “There’s simply not enough information to decide if these treatment plants are operating lawfully.”

Terry Lodge, the OH attorney who has specialized in environmental and energy issues since the late 1970s, says that relying on data from Pennsylvania is the only way to know what is really going on in Ohio, since Ohio does not collect data about the origin or disposition of the fracking waste moving within its borders.

“[They] rely on the fundamental honesty of someone whose business model relies on having absolutely minimal regulation,” said Lodge. “Waste is coming out of every pore in the industry, and they have to come up with creative ways to handle it.”

Since the half life of radium-226 is 1,600 years, that means it takes 16 centuries for one-half of the nuclei of a radium particle to decay.

“This is an incredible, effectively permanent problem that is being created daily,” said Lodge.

caption: Chris Cornwell fishing in Glacier Lake in Mill Creek Park in Youngstown, Ohio. Water bodies identified by Public Herald in this report are popular for fishing. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Dr. Julie Weatherington-Rice, an earth scientist and adjunct professor for Ohio State University with a Ph.D. in soil science, says that the already minimal testing requirements in Ohio are only getting “weaker and weaker,” which means there is no way to verify what is coming in and out of these facilities.

“[Tests] have been watered down and watered down until we have almost no rules at all,” said Dr. Weatherington-Rice.

Pennsylvania Gov. Wolf’s administration, in coordination with Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, announced July 26 that it would begin to require quarterly testing of leachate for radium at all Pennsylvania landfills. The move comes five years after the release of the DEP’s 2016 TENORM study, which found that radium in landfill waste was a cause for concern.

Public Herald editor-in-chief and co-founder Joshua B. Pribanic provided the following statement on the Wolf administration’s announcement:

“After two years of Public Herald investigations exposing the statewide radioactive leachate problem, DEP’s response — while a step in the right direction — barely scratches the surface of the science required to tackle this problem. Worse yet, DEP has again attempted to downplay the TENORM issue by releasing false propaganda about its 2016 study. While we hope the attorney general’s response would bring criminal action for the state’s negligence on this issue, it appears the release of this material for over a decade into public waters will likely go uncharged. Public Herald will remain steadfast on informing the public and holding the governor, the attorney general, the DOH and the DEP accountable for their actions.”

The DeWine administration in Ohio, however, has yet to make a similar regulatory move, leaving a hole in the knowledge the state has of what’s going into and coming out of its landfills and treatment plants — a point echoed by Dr. Weatherington-Rice.

“Those gate posts [at landfills] were never designed for that kind of [low level radiation] scanning. They were designed for hospital waste, [for something that decays rapidly],” Dr. Weatherington-Rice said about places like Pennsylvania and Ohio who don’t use gamma spectroscopy to figure out radium levels in each load of waste. Without that kind of testing, she says, “They don’t know what they put in that landfill. They think they do, but they don’t.”

While rules still exist in Ohio concerning the testing and facilitation of waste disposal, they are scant and do little to control radioactivity. If future legislation does not address these issues, the health of Ohio’s waterways will continue to be put at risk.

Investigative Journalists Joshua Boaz Pribanic, Melissa A. Troutman, Jake Conley and Elijah Labby contributed to this story

Funding for this series was made in part by the Park Foundation