“If Only I Would’ve Known” Oil & Gas Whistleblowers Speak Out About Exposure to Radioactivity on Fracking Jobs

Andrew Gross tests for radioactivity in the Marcellus Shale Play with Public Herald. Gross told our team, “Pennsylvania is definitely the wild west when it comes to radiological health regulations. I’ve never seen anything like it. And for me, especially being a guy from Louisiana, that really strikes me as odd, that we’re so much better off down here than all of the people who are so smart up there.” © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

“If Only I Would’ve Known”

Oil & Gas Whistleblowers Speak Out About Exposure to Radioactivity on Fracking Jobs

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

DONATE

Public Herald is a nonprofit newsroom that holds those in power accountable. You can receive our latest breaking stories by subscribing to our newsletter or becoming a Public Herald Patron.

by Kristen Locy and Justin Nobel for Public Herald

December 14, 2020 | Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers

“They’re Going to Die” – Experts & Whistleblowers Reveal Life of Trafficking Radioactive Waste

The year is 2014, and the sleepy mining and agricultural towns of Northern Appalachia have transformed into gold-rush towns. But this is a new type of gold – Shale gas.

These towns sit above an underground formation called the Marcellus Shale that could help make America the world’s greatest producer of natural gas – and in 2014 the Marcellus region is booming. The restaurants are buzzing, bars packed, hotels full for the first time since many people can remember. Each generation of this area has seen the boom and the bust of other major industries – timber, coal, steel – and shale gas is the next one. It’s marketed as energy independence, good paying blue collar jobs, the American Dream. In areas where decades of economic decline have created a culture of need, this dream is welcomed with open arms.

Tom lives in Eastern Ohio and sells used cars. He works long hours and starts to notice out-of-towners from states like Texas and Louisiana come in wearing cowboy boots and looking to buy fancy new trucks. Everyone seems to have money to spare, except Tom. When he asks the men what they do, they describe an interesting trucking job he’s never heard of before. It involves 10-12 hour days sitting behind the wheel of a “brine truck” hauling “water” from the fracked gas wells popping up across Pennsylvania and West Virginia to sites in Ohio called injection wells. With overtime, you can make $60,000 a year or more. And unlike most trucker jobs where long hauls are the norm, you are home with your family every night. Tom could make twice the pay he makes now, enough to pay off decades-old credit card debt and send his kids to college.

An hour east of Tom, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Brandon is hearing about the same economic dream. He grew up in an industrial town as Pittsburgh’s steel industry died and crumbled. Running through his town was Chartiers Creek, which has long been one of the most industrially polluted streams in the region. As a kid, it was common knowledge to stay out of that water. Yet – he saw the environment start to bounce back as industry left the area and regulation increased. Starting his career as a young environmental professional in the 2010s, right after the Great Recession, he saw the oil and gas industry as a welcome new opportunity for the area. He thought, “We’ve learned from the mistakes of our past, and this is an industry that can finally be properly regulated to protect the health and environment of the area.” In 2013, he took a job with a local environmental cleanup company, Sunpro. They focused on hazardous material cleanup for oil and gas operations. The pay was good, the hours long, and they often worked for some of the big players in the Marcellus of southwestern Pennsylvania, like Range Resources. Brandon thought, “Regardless of how many regulations you can have in place, accidents happen,” and he had the skills and tools to make sure any hazardous materials were properly cleaned up. He and his colleagues took their jobs seriously and worked hard to make sure it was all done according to the books.

caption: Former oil and gas worker Brandon Novogradac at the Chartiers Creek sewage plant discharge next to Arden Landfill in Southwestern Pennsylvania. © Nina Berman for Public Herald

Now the year is 2020. Brandon is standing next to Chartiers Creek, about 20 miles upstream from where he grew up. He left the industry a number of years ago and now owns his own business that provides holistic support for people dealing with serious illnesses like cancer. Nearby, foamy water spurts out into the creek from a massive concrete pipe leading to the local municipal sewage treatment plant. There’s evidence people come here to play – fishing lures, well worn paths, a lonely muddy sock. Across the stream is the local municipal landfill, Arden Landfill, where he used to drop off waste from the drilling process when he worked for Sunpro. In the past decade, this landfill has received over a million tons of solid oil and gas waste and is now one of the highest geological features in an area known for its rolling hills.

When asked if he would have taken that waste to the municipal landfill if he’d known what was really in it, Brandon said, “No. Of course not.”

The Industry’s Black Box

Oil and gas workers are the industry’s black box. A living testament — and a living test kit — to an outrageous set of hazards thrust upon them by bottomline-hungry employers. For those of us reporting on and living with fracking, this part of the puzzle has always been a mystery: What happens to these workers at the wellhead and, equally as important, what happens to these workers between the wellhead and the landfill, the well head and injection well? The risks these workers face has never been appropriately examined, and up until now, their full story has never been told. Among all the risks, including hundreds of toxic chemicals and known human carcinogens like benzene, there is a risk that remained below the surface of the earth until the workers dug it out – radioactivity.

Although the media rarely discuss it, and the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) —the branch of the US government charged with protecting US workers — remains mum, the industry has known for decades that oil and gas production brings an incredible amount of radioactive waste to the surface. It comes up as a toxic salty liquid the industry refers to as “brine” or “produced water” in the form of drill cuttings from fracking bores cut through radioactive black shales, and as various mineral scales and sludges that form on piping and in tank bottoms that can be, in the words of one radiation control consultant, “much hotter than most stuff in nuclear plants.”

caption: Test results obtained by Public Herald from the 2016 DEP TENORM Study show unconventional produced water containing up to 26,600 pCi/L of Radium-226.

One major risk involves the industry’s truckers, who haul various wastes from wellhead to disposal site, often thinking they are just hauling water or dirt. A loophole called the Bentsen and Bevill Amendments, part of an act from the late 1970s called the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act that intended to manage the nation’s hazardous waste streams, led to a stunning exemption from hazardous waste law for the oil and gas industry.

Since 1988, even though the major companies and the US EPA are aware oil and gas waste contains toxic heavy metals, carcinogens, and radioactivity, the nation’s Environmental Protection Agency determined that regulating the waste as “hazardous” would cause “a severe economic impact on the industry and on oil and gas production in the U.S.” Thus began decades of transporting the waste in unmarked trucks driven by men like Tom and Brandon who were in the dark as to the true contents of what they were hauling.

This relentless push for deregulation, in pursuit of the idea that peeling back burdensome rules makes industry and jobs flourish, at the end of the day puts the wellbeing of a worker at risk.

Truckers Break Their Silence

In two exclusive interviews, Public Herald speaks to a truck driver and hazardous material technician who worked during the boom of the Marcellus fracking industry. They say that, while there was money to be made, the potential devastating risks to their health and their families are a cost that nobody has calculated or appreciated, until now.

Brandon and Tom take us behind the scenes into the dirty, gritty and radioactive side of fracking, a world so absurd it seems unbelievable. In fact, it may be hard to comprehend that workers like these were put into these shocking situations while working for the richest industry in the one of the richest, most ‘civilized’ nations on planet Earth. And yet this happened, and even as you hear Tom and Brandon speak, this is still happening to other oil and gas workers like them, in the US and around the world.

We have heard from environmental advocates, politicians, regulators, and the oil and gas industry executives. But these are the voices we have not heard.

Tom the Brine Hauler

Tom McKnight: Back in 2012 and ‘13 the oilfield was coming on strong, and a lot of us noticed out-of-town people coming into this geographical area. At the time I was selling cars for a living, and I actually saw the increased incomes, the bigger paycheck stubs and everything coming from it…You’d see the hotels fill up, you’d see the restaurants filling up, all kinds of southwestern talk, you know, the hillbillies coming in with their cowboy boots and their cowboy hats and the environment it just went boom all the sudden, it changed…So I thought well, gee wiz, you know these people were earning this kind of money, I am gonna look into this, so I went to one of these trucking companies that moved in from Pennsylvania.

Oil and gas brine hauler, Tom McKnight. © Tom McKnight

I was just out for a ride with my wife on a Sunday afternoon, and I drove through the back of the parking lot of the company that was closest and there was a guy working in the back and he asked what I was doing there and I told him, I said “I heard it’s a good place to work,” and he shed his coveralls and took me into the general manager’s office. He turned out to be the general manager himself, and you know we sat down right then and did the interview, no phone calls, no introductions, no points of reference, no nothing. He was just happy to get somebody that was wanting to look at the positions, because their big thing is they just had to get a lot of people working as fast as they could to handle the amount of business....and there I was — a brine hauler.

I do not remember anything more than the risk of driving with a high center of gravity and pinching off fingers and stuff, when you are hooking up hoses and doing things like that. They put us in an orientation class and I thought at the time that it was extremely comprehensive. They spent hours on H2S, they spent hours on explosive gases. They had different programs all the way through with the major oil companies in the area that had their own videos set up and how to do it on their particular site when you arrived on their site, and it was very extensive. The only thing though, they never talked about radiation, and I remember specifically someone in our orientation class bringing up radiation and the guy, Frank McNight is his name, who was putting on the orientation class for CS Trucking, held up his cellphone and said you will never get more radiation than you are getting off of one of these right here. So we all just, you know, “Oh okay that’s great, nothing to worry about there.” Basically they said anything that’s not fresh water is brine, so no matter what you’re hauling, if it’s not fresh water it is brine.

Life as a brine hauler. © Tom McKnight

While the oil and gas industry innocently refers to the material Tom regularly hauled as brine, or salt water, or often just, “water,” records from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP) show that levels of the radioactive element radium can be 5,700 times the EPA safe drinking water limit at 5 pCi/L, and 443 times what the Nuclear Regulatory Commission would allow in the discharge pipe of a nuclear power plant or uranium enrichment facility – ie, 60 picocuries per liter for both radium-226 and radium-228, which, in emails to Public Herald, the EPA has conveyed is the same level the agency has defined for liquid waste as “radioactive.”

Meanwhile, according to a lengthy commentary released this spring by the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, the sludge that settles out at the bottom of ponds of “produced water,” or brine, can contain radium at levels more than 1,000 times background and more than 200 times what would be permissible at a Superfund site, the nation’s infamous highly toxic waste sites.

But Tom knew nothing about any of this. From 2013 to the end of 2017, he worked the heart of the Marcellus oil and gas field, a sweet-spot of production that runs from northwestern West Virginia up through southwestern Pennsylvania. Waste spewed up by fracked wells in the first weeks of production is filled with toxic chemicals from the fracturing as well as heavy metals and radioactivity – the slurry is referred to as “flowback” and stored on site in large “frack tanks” or wastewater ponds called “containments.” The brine or produced water that comes later, and will flow for the rest of the well’s producing life, is stored in more permanent brine tanks on site.

After decades of spewing brine into ponds and bayous, the most popular current manner for disposing of brine is to shoot it at high pressure back into the earth at “injection wells.” But many of the injection wells that Tom regularly hauled his oil and gas waste to were in eastern Ohio. So, he was constantly crisscrossing the region in his brine truck. It, seemed, at least initially, that there was never a dull moment.

Tom McKnight: I was extremely excited, I had a lot of fun with it. There was just so many water trucks out there and so much inexperience and so much of a “Damn the Torpedoes, full speed ahead” attitude. We were hauling in freshwater, we were hauling out dirty water. The whole time we were there there’s dump trucks hauling out tailings, what did they call that again—drill cuttings!

The dirtiest stuff that I hauled on a regular basis was after the well was drilled, after the fracking was done, the, they called it “bringing it online,” and they would go down and cut these plugs out and that first initial burst of water was just some really dirty stuff, sometimes it was as black as the screen of your phone when you shut it off, just black. I spent a lot of time underneath that rig literally getting rained on when they were pulling the pipe by that water. You would be out there just literally vacuuming up this water that was laying down on their containment around the rigs. The other thing was while they were doing that they would have sometimes six or eight frack tanks, and all the water that would come out of there they would put in these frack tanks and what they would do is let them settle in one frack tank, and then settled out water they’d move to the next one, and the next one, and so on. So we would haul that water away too, and while they were bringing them online and letting them settle out that would be a flurry of trucks, constant trucks. Constant trucks, 24-hours a day. So, that was all really dirty…

When they go from that series of frack tanks and bringing them online to putting them in the regular storage tanks that they have permanently onsite, we would go in and clean out those frack tanks so that they could move them. So, first thing we would do is suck all the water out. The second thing we would do, and it may not be our company, a different contractor might come in, come in with what we call a super sucker and then they would, they would literally get somebody in there with shovels and that super-sucker and, these things suck so hard it can actually rip your arm off you know, but they get in there and they pull all these solids up and they would take them. They would take it to a dewatering facility to make it dry so they can put it in a landfill.

We’d be hauling brine for let’s say a month, so as you’re hauling brine, that sand actually builds up in the bottom. Every time you haul it just gets a little thicker, so if they got an order for fresh water we’d take our truck back to the shop, they’d pop the manhole off, send the guys in with a shovel, shovel it all out then send them in with a pressure washer, pressure wash it out and rinse it and so them guys would be all exposed to that to you know they’re right in there breathing it and all being around. You take a shovel in and uh, you know scrape it all down, shovel it out, take a flat shovel you know, and you start on the sides because they are rounded and just sort of scoop to the middle, and just basically just have, there is another guy outside, and he would be holding a bucket up or a big pan or something and you shovel it in there, and then he would take it over and we would have a hopper there that basically go to, it would go to disposal too, every once in a while we would have to have, you know, the landfill bring their roll-back truck and haul it away.

They supplied us with yellow neoprene rain suits. A face mask, and a respirator, one of the rubber ones with cartridges on the side. Management had the attitude like, “Hey we can lead a horse to water, but we can’t force them to drink. If they won’t wear the PPE, we are not gonna force them to do it,” you know?

The one time I related to you that I was sent to clean out frack tanks after they were done bringing online a well, and I opened the manhole in the front which is about 18 inches around and has a series of butterfly nuts and you take a hammer and you knock those butterfly nuts off and then I open them up, I stuck my head in, I stuck the two inch hose in, I guided them down to the very bottom sump of the tank so I could clean them out and get as much water as possible out of them. The end of that day my head, my head underneath the hard hat and above the neck line looked like I been down in Florida out in the sun all day and the little spot, the in-spot between my gloves and where my shirt started was also all red like a sunburn. And I don’t know whether that was a reaction to the salt, but now I’m wondering if it’s not a radiation burn.

caption: a video published by the company Covanta, who treats radioactive fracking waste in New Castle Pennsylvania, shows workers cleaning out tanks.

I seen guys go in there just with their T-shirts and blue jeans on and a face mask, you know, depends. You know some guys are tough, they don’t care. But for the most part, coveralls, and they were instructed to just use Dawn dish detergent to clean up when they’re done. So there were no precautions made, they were made to do their own laundry at home you know, or whatever, or in the hotels, you know? They would also have to bathe in Dawn dish-soap, just like we see the commercials when Exxon-Valdez went down and the volunteers cleaning off the little ducks with Dawn, same deal.

Justin Nobel: Did someone instruct them like, “This is the appropriate way to wash yourself after you have been in a frack tank? Bathe with Dawn dish soap, or…”?

Tom McKnight: Yes, yes I believe that’s true, yeah.

Justin Nobel: And then where would the clothes be washed?

Tom McKnight: Well I would imagine, like, if I brought those clothes home my wife would just shit, so I imagine they get them in a bucket and get them rinsed out with Dawn dish soap as much as possible before they get put in a regular washer.

Justin Nobel: Would they ever be wearing a respirator, or TYVEK suit or a dosimeter that would be measuring radiation?

Tom McKnight: I would say yes to the Tyvek suit. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a radiation monitor on anybody around anything that I did.

Brandon the HAZMAT Technician

Around the same time, and in the same vibrant part of the Marcellus, Brandon was working as a hazmat tech for some of the biggest companies in the oil patch, cleaning up some of their most dangerous waste.

Brandon Novogradac: People cared what they were doing. We had a strong safety culture there, which is huge. A lot of places it’s lip service to safety, but its not really carried through in the day-to-day practice. I would say that we had all of that there pretty strong. At least at the time. And then most of the spill response that I was involved with was either for, like, two bigger clients at the time, one was Mark West which is a pipeline company, and we did a lot of work for them out in Ohio. And the other was Range Resources.

We did emergency response for both of those clients, but then we also did, like, normal waste removal services for both of those clients as well.

So you were asking about spills, though, so I’ll start there. Like one that I remember well because I was sort of managing it was they had had, like, a brine spill off the corner of a well pad, and I’m not sure exactly, like thinking back I don’t remember what caused it, but I feel like they sort of overtopped a holding tank with brine that they’d either brought in from somewhere else or it may have been flowback from the well. It spilled off the corner of the pad, and the nice thing about brine is, it’s saltwater right? So we just used the soil probe and had excavators out there to clean up the affected soil. And by clean up I mean removed from site and then that just goes to the landfill. Tons and tons and tons of earth…you know…it’s pretty…when that happens it’s super extensive for them.

But we had scaling PPE anywhere from just wearing like boots and jeans and FR clothing – flame resistant because that’s required on site in that industry – anywhere from that up to a full splash suit, a respirator, with gloves and rubber boots taped over everything else.

Yeah, so like, for a brine spill really, like, boots and jeans were considered adequate.

But the thing is, it’s really hard to control your risk completely when you don’t know exactly what you’re dealing with.

Kristen Locy: So what did they talk to you guys about in terms of radiation? Did you guys have any sort of testing for that when you were in the tanks?

Brandon Novogradac: No. That’s a really good point. I mean, well…I guess yes and no. It’s something that I feel like we sort of, we sort of started to do better. You know after we had been working at this for a little while. And kind of seeing what the waste was doing. So yeah, after a while we did start taking gamma scanners with us.

So we would take this waste out of the frack tanks because the frack tanks can’t legally go down the road with the waste loaded. So we would take them and put them in those roll-off boxes so they’re like 10 cubic yards. Some of them are called “vacuum boxes.” Vac box. Because you can actually vacuum the waste straight into them with a vac truck. But here’s the thing, so if we had the waste sitting in those, in a vac box say, like you can open the top hatch on that vac box and you can put your Geiger counter or gamma scanner or whatever you wanna call it, the brand we used was called Ludlum. And you could open the hatch and either hold the Ludlum right there at the port or you could maybe put your arm in it up to your elbow and just kinda read. So what it would do, though, so you might originally have, like, a gamma reading, a gamma radiation reading slightly above background.

We’ll just say background is 10. So we might get a reading like 17 or 22 so it’s like, I mean, you know, big deal. Double background is almost nothing still in my mind at least. But then if it sits, you know, and you check again in like a few days it might have gone up, you know maybe it’s in the 50’s. And then, like, at some point in the future it’ll peak, you know, at whatever level it’s gonna peak out at. It’s just strange to me that like…over time if waste sits…if you’re waiting for approval for disposal somewhere, you’ll see higher and higher gamma radiation measurements off the stuff.

But this was just sort of like, coming into our collective consciousness. And so there wasn’t that up front training. It was like we were learning as we went with that. And it was sort of like it was an awareness that was creeping in when I was working there, and I feel like it was no fault of anyone at Sunpro, you know? I feel like maybe we were under-informed by our clients. Because of course they have, you know, they’ve been doing this for decades by that point, and they had to have a better handle on what was coming back out of the ground in the flowback.

Kristen Locy: They would’ve known, yeah.

Brandon Novogradac: Yeah, so that feels like a deliberate failure to disclose…

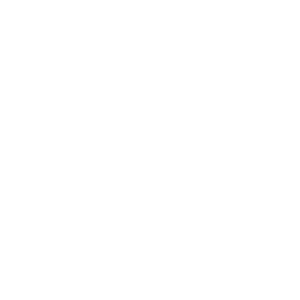

Andrew Gross: Digging up the Industry’s Dirt

Andrew Gross knows all about the failure to disclose . He grew up in the rough-and-tumble 1970’s Louisiana oil fields, and in the early 1990’s operated a company called Radiation Technical Services that had contracts with some of the biggest oil and gas companies on Earth. Radiation Technical Services cleaned up the radioactive mess companies often left behind in the oilfield.

Gross knew the oil and gas industry’s workers intimately because he worked with them every day, and he knew the risks they faced, too. He has been out in the oilpatch, listened to its noises, breathed in its smells, and he collected its waste in little lab sampling jars. He hasn’t been in some swivel chair far away from the action of the industry, he has been out digging in the industry’s dirt.

Andrew Gross straps in equipment to his vehicle after testing for radioactivity in the Marcellus Shale Play with Public Herald. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

Gross has been in the legal trenches too, serving as an expert witness in cases involving oil and gas worker radioactivity exposure that somehow have remained invisible to the world. As unreal as it sounds, a set of Louisiana legal cases, some settled as recently as 2016, show workers doing a variety of common industry jobs –roughneck, roustabout, pipe cleaner, truck driver hauling sludge – developed cancers, and those cancers were linked using a radiation dose analysis program created by the CDC to the radioactivity exposure workers received on the job in the oil and gas industry. Sure, Gross doesn’t have a PhD, as he readily admits, but he knows where the bodies are buried.

Andrew Gross: I was trained in the Navy as a health physicist in the Navy, spent nine years there, and when I got out I went to work for energy for a brief period of time, and then I started my own company. And the object of my company was, the NORM [naturally-occurring radioactive material] regulations were pretty new at the time so we, the objective we had was to help the industry comply.

NORM, you know, NORM is a nice word the industry invented because it doesn’t sound like what it is, which is enhanced radioactive material. The oil and gas industry has known about this since at least the 1950’s and likely the 1930’s, from the documentation we’ve discovered over many years of discovery, and just chose to ignore it like they did with so many other things. So, if you think about the half-life of radium-226, which is the main isotope of concern or the main one we talk about anyway….

Justin Nobel: One Thousand – Six Hundred – Years…

Andrew Gross: …So, this does not go away very fast, that is the problem, and it builds up over time.

In the nuclear industry, in the Navy also for instance, you are very concerned about contamination, so contamination is controlled very tightly because the problem is you can get it on your clothes, take it around to all over, it can spread very easily. You take that home on your clothes and your kids get into it and that’s the sort of thing that gets in your lungs and you have these alpha emitting radioactive isotopes which are just pummeling a small area of your lungs for years and years and years with these powerful alpha emissions, and it’s incredibly unsafe.

Andrew discusses a specific oil industry task called “pipe-cleaning.” It involves chiseling out a difficult-to-remove mineral deposit from the vertical piping that brings product to the surface. This deposit is called “scale” and contains extraordinarily high levels of radium, levels that have literally been reported at tens of thousands to even hundreds of thousands of times above background.

Andrew Gross: They have this thing that goes down the middle of these pipes and kind of shaves off all of that stuff and shoots it out the other end, and there’s a guy at the other end, who’s also rattling. So, this stuff is flying out, and we have found concentrations like 50,000 picocuries per gram radium-226 in this stuff, and it is horrible.

In one pipe yard that was particularly egregious, we went to workers houses and found in there, like the laundry – what do you call it, the lint vent – in the lint vent, the lint of the laundry was incredibly hot, the carpets were very contaminated, bedding, clothing, and they were two little toddlers walking around on the floor, it was just insane.

Just as much concern is for the guys who are going and cleaning out tanks. The guys who clean the tanks are also in significant jeopardy, and they should all be wearing personal protective gear, just like you are seeing nurses wear, only better quality, half-faced respirators, not N95s.

Justin Nobel: Radioactive risks exist for not just oil and gas workers, but the families of oil and gas workers too..?

Andrew Gross: Hundred percent. And this is not theoretical, we have seen it many times. Many, many times. If I were them I would want once a month at least to have the cab of the truck surveyed with some wipe samples to make sure there is not a buildup inside the cab. If your interest is in protecting workers and protecting the public from exposures, simple things can be done, simple PPE and decent respirators which are only 15/20 bucks a piece can make, can lower that risk 80 – 90 percent right off the bat. And when it comes to the public, checking those tanks to make sure they don’t have radioactive material in them before they go. That is the simplest thing they can do and it will save so many lives and so much time and money for them down the road, and for the life of me I don’t understand why they’re so resistant to it.

Justin Nobel: How has this been allowed to happen? If everything is as bad as people like Andrew Gross says it is, then why hasn’t anyone pulled the lever long ago on this 10,000-alarm-bell fire? Officially, the first producing oil and gas well in the United States was in Titusville, Pennsylvania. Invariably it spewed up radioactive brine, and the pipes that carried the product to the surface would have eventually built up a mineral scale that likely became radioactive. How is it possible that this issue has gone unseen, at least in the eyes of the public and the industry’s own workers, for 161 years..? Andrew had some ideas.

Andrew Gross: You have a community that is economically distressed and, you know, they get a job, and it’s a good job. The jobs pay decent money, so it’s not, it’s not like they are working at WalMart or something, you know? They get a few bucks more an hour, so their first priority is gonna be feed their families. These jobs are not meant for somebody with a master’s degree, they are meant for someone who maybe went to high school or whatever and needs to make money and feed his kids. The big fear when we go into any area, and one thing the oil industry would always say in Louisiana, is that we’re killing them with lawsuits. That we’re driving away, that we’re killing jobs, which is nonsense. As long as they make a profit they don’t care. What we’re doing is trying to hold them accountable. But they don’t like that.

Andrew Gross takes a soil sample in Pennsylvania to test for radioactivity. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

A corporation exists for one reason, it’s to make profits for its shareholders. That’s it. That’s the only reason it exists. Shell can run as many commercials as they want about how they’re stewards of the environment and taking care of the Gulf of Mexico; they exist for one purpose. If you’re the CEO of, you know, Exxon, and your concern is your shareholders and your profits this quarter, so you are not spending money on any environmental nonsense that you can avoid spending it on. If people understand that on a base level then, you know, especially legislatures, then you can kind of have a system where corporations can also be held accountable, but the system is just very rigged in so many places. Industry is very powerful.

Justin Nobel: Okay but I guess the big takeaway for me was that, exposures, especially over the course of time in the industry, appear to be high enough to cause cancers in workers, can we say that? Or that’s been shown?

Andrew Gross: Definitely, definitely.

Certainly going back many years they’ve had health physicists on their staff who have told them about the risks from the radiation. They bring in top-flight scientists on their side, and we beat them all the time because the reality is, you know, they are involved in making a lot of excuses and having to explain away things and our simple point is, ‘You are exposing people to radiation they shouldn’t be exposed to, and you’re not even telling them about it.’ Now the official stance in the federal government and internationally is any dose carries some risk, no matter how slight. With radiation, any dose can have an effect, so for them to say it is perfectly safe is just utterly irresponsible.

Two hours of training with people and just a couple dollars worth of personal protective equipment can lower their risk 80 percent, easy. That’s what’s so crazy, it’s so short-sighted for these companies to not just do that. That is one of the problems, there is not any, you know, a sort of, one set of regulations, so it varies from state to state to state. But Pennsylvania is definitely the wild west when it comes to radiological health regulations. I’ve never seen anything like it. And for me, especially being a guy from Louisiana, that really strikes me as odd, that we’re so much better off down here than all of the people who are so smart up there.

Andrew Gross uses a device to sample for radioactivity in Pennsylvania. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

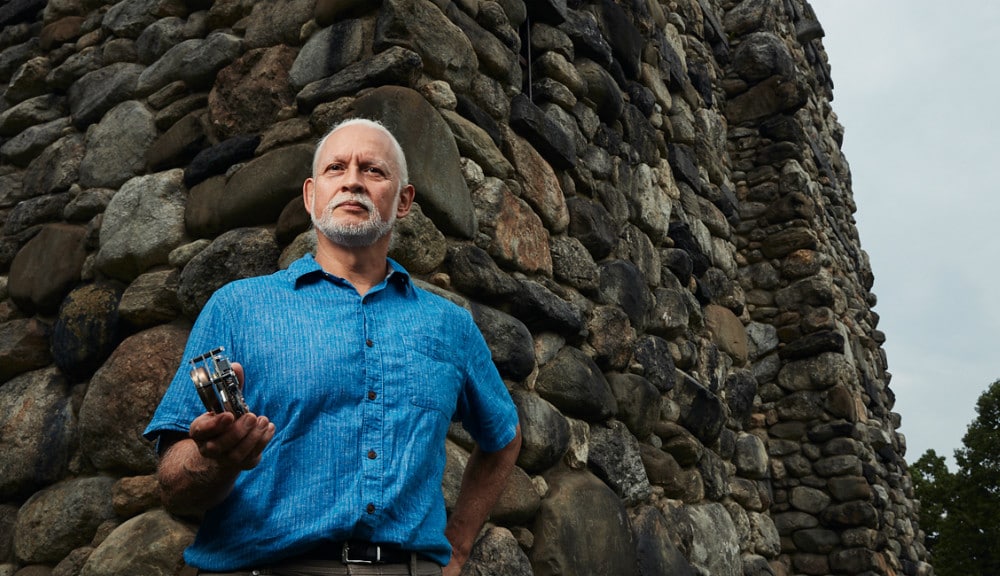

Nuclear Forensics Expert Dr. Marco Kaltofen: Sherlock Holmes with a Geiger Counter

Where Andrew was the salty guy who learned in the field, Marco is the careful scientist who is not afraid to go into the field. He has testified as an expert witness on radioactivity in numerous legal cases and before the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. He has tracked radioactivity on five continents, a bit like Sherlock Holmes with a Geiger counter. He knows his radionuclides inside and out. In the 1990s, Marco said he would regularly be locked out of the buildings he needed to inspect in post-Soviet Eastern Europe while working for Greenpeace ensuring remote laboratories weren’t secretly constructing nuclear weapons. This was not a problem for Marco, he says. He simply had to test the doormats to know exactly what was going on inside the facilities. In St. Louis, Missouri in the 2000s, Marco helped solve a radiological mystery by tracing the radioactive daughter products leftover from 1950s uranium refining operations into local streams and people’s backyards. In more recent decades, Marco has turned his eye to oil and gas radioactivity, and fracking. What he’s found is a shocking revelation for anyone who thinks that oil and gas worker’s radioactivity exposures are insignificant.

He also is pretty good at explaining it all.

Dr. Marco Kaltofen. © Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Marco Kaltofen: Now, first I understand, soil has a little bit of natural radioactivity. I mean our planet is made of star stuff, and guess what? Stars are radioactive. There’s a little bit of it leftover in our world, that’s why the core of our planet is molten. It’s the radioactivity that’s keeping it heated. There’s something we didn’t know. Lava is basically made from a radiation cooker. Well a little bit of that gets up here, we’re used to it, some of us die every year from it which is bad – but we’ve given a number and we said this number is normal and this number is not.

That’s a lot of words but essentially, you know, the words come down to ‘yes, the radiation is living in underground formations, we bring it to the surface, we don’t want it, it’s a waste, we don’t really know what to do with it.’ So all these different regulations are just trying to put lots of fingers in lots of dikes and plug a lot of leaks and try and keep this radiation under control once it’s at the surface.

The EPA needs to know, well, who made the radioactivity? And what were they thinking when they did it? And what product were they going to sell? Now for me, as the scientist, all of that is 100% irrelevant to radioactivity. Radioactivity is radioactivity. It’s physics and the nuclear physics in Massachusetts is exactly the same as the nuclear physics in Alabama and Washington and California. But as a regulator, we treat radiation from different places differently. So if an oil and gas company made a certain amount of radiation, they don’t have to report it and they don’t have to dispose of it in any particular way, they really don’t have to do a whole lot, they are exempt. Whereas if the same amount of radioactivity were made by a white-haired, pony-tailed researcher in Massachusetts, I’d be filling out forms and paying for disposal till the cows came home. The radiation might be the same, but because it came from the oil and gas industry we treat it differently. To a scientist, this is always a mistake. There’s no scientific reason for saying radioactivity from X is fine but radioactivity, eh, I don’t like yours, it’s bad. That’s something we have to get over. And it’s going to be difficult. It’s foolish to expend resources on radioactivity carefully in one case and carelessly in another.

Marco also has some good thoughts on the inevitable, “Why” and “How” questions – Why has this been allowed to happen? How has this been allowed to happen?

Marco Kaltofen: There are a lot of jobs where the regulatory agencies have not caught up. Changing regs takes a long time. At a minimum, consider it takes a change of administration for most new environmental laws to come through. That’s certainly true now. And the time frame for regulation is measured in a decade or more. So we haven’t even got people looking at the problem yet at the upper levels of managing agencies. So, certainly, your average inspector is going to be unfamiliar with many of these different things.

If you’re working with radioactive material, it’s normal for people to bring their work home with them. You work in the oil fields, your clothes have oil on them, your washing machine has oil on them, your spouse probably makes you wash all your stuff separately, some people even have a separate washing machine but I’m collecting data, whereas people in the house are collecting dose. They’re getting exposed to that material that the worker brings home. So really it’s a family affair. Now the harder question is not, ‘where do you find the traces of radioactivity’, – the hard one is, ‘how is it actually affecting people – what can they do to reduce their dose and reduce their risk? What are you going to do about all this data now?’ And suddenly it’s less scientific and now it’s a decision about policy and ethics and desire and the emotional feeling of safety, and then there’s a bit of human rights sprinkled in – in that, is it okay to expose someone to a dose that you think is acceptable but you haven’t really worked that out with them? There’s an element of consent that’s missing.

“If Only I Would’ve Known”

In 2019, two years after leaving the job, Tom McKnight was diagnosed with thymoma cancer. Although he received a successful operation to remove the tumor, doctors later discovered nodules on his lung, and a growth on a bone in his hip. Survival rates, Tom found on the American Cancer Society’s website, are scary. No matter who wins this next presidential election, odds are that by the time Americans vote again for president in 2024, Tom will be dead.

Now let’s make it very clear – Tom does not believe his cancer is linked to his oil and gas work. But as he describes it, if you have no idea you are being exposed to radioactivity, you also have no idea how to avoid its harms.

Tom McKnight: I’ve seen people stick their finger in it and stick it in their mouth before, but for the most part we have all tasted brine because sometimes it splashes up, you know. And I’ll tell you, to be honest you know, we were, I was probably guilty of it more than others, but when I was working around it when it was time to eat, sometimes I would open my sandwich bag and I would try to roll the sandwich baggy down over my hand and never touch the sandwich, but yeah I’m pretty sure I ate some dirt though too. Every potato chip you ate, you touched.

Memphis Jane Hill holds soil samples from Public Herald that will be tested for Technically Enhanced Radioactive Material (TENORM) at the University of Pittsburgh lab. © Nina Berman for Public Herald

Of course if we knew that there was a radiation problem we would have taken precautionary steps and made sure we had respirators, and made sure we had the right uniforms and gloves and protective PPE for that, you know, and it would have cost them more money. And I go back to what I said 3 or 4 times through our conversation, that if we are forewarned with what’s gonna happen we can deal with it, but if we ignore it, it’s just silently out there, polluting our environment, getting our people sick. You know, and it’s an unrecognized cost of the oil companies by not having to deal with it.

In retrospect, I sure wish I would have had some training, and been prepared for it. At least at that point I kind of could have went in with my eyes open, and then I wouldn’t have had anybody to blame but myself, and we probably would have had established job practices that would have eliminated our exposure to things we didn’t even know we were being exposed to. So, do I feel bad? In retrospect, sure, I feel bad. I feel a little mad, because I just can’t believe that management, and the oil companies, did not know there was a good bit of radiation in there.

Tom and his son. © Tom McKnight

Tom and his daughter. © Tom McKnight

Tom and his family. © Tom McKnight

I loved the economical impact, that was awesome, that was great. You know, but my point in life was, all my children were coming up in age. One was going to college, one was already in college, one was getting ready to go, and it just made life easy, you know. It was just so easy to peel ‘em off a couple hundred bucks for groceries or fill a car with groceries and go visit them. I paid off my Visa that I never had paid off since like 1982. It just made it so that I could buy the house that I was living in versus just living in my mother-in-laws house, you know. So it was a, the carrot that was out there was really big, I sure appreciated it. But at what cost? I surely wouldn’t knowingly want to put radioactive brine on the roads to keep dust down, or radioactive brine in the, in the ice control trucks in the winter to keep the ice melted. That’s insane.

Justin Nobel: This, by the way, is legal in at least 12 US states, including Michigan, New York, Ohio and, until very recently, Pennsylvania.

Tom McKnight: And I would certainly do without any kind of economic better lifestyle to save our environment, you know, that’s.. that’s nuts. It’s just nuts, and then to have the governmental agencies that could be responsible for this shuffling off responsibility and saying, ‘hey, that’s the other guy and that’s not me,’ and then the industry totally just, you know, operating like, ‘well let’s just keep them between themselves and we can go do our jobs’ – it’s wrong, you know, and I don’t think there needs to be new laws, I think they need to tie everything together and have some accountability.

You know, if they know that that’s there, they know that those regulatory agencies are ignoring the problem or passing the buck, they’re gonna shrug and say, ‘hey we’re just operating within the boundaries that are set up for us.’ It’s America. It’s capitalism, yo.

It’s like I’ve always told my kids, there’s a difference between right, and right to the letter of the law.

Memphis Jane Hill handles soil samples from Public Herald that will be tested for Technically Enhanced Radioactive Material (TENORM) at the University of Pittsburgh lab. © Nina Berman for Public Herald

While Tom was working as a brine hauler, Brandon was experiencing something similar in another part of the massive Marcellus oil patch and coming to the petrifying realization that even when he was being protected by his employers against radioactivity, he was not being fully protected.

When a radioactive element “decays” it blasts off a tiny explosive piece of matter or energy – what we know of as “ionizing radiation.” The three main types of concern are gamma rays, beta particles and alpha particles. While alpha particles can be blocked by a piece of paper or your skin, and gamma rays can go through feet of concrete and steel and may seem the scariest. In an occupational setting like the oil and gas field, it is actually beta particles, and especially alpha particles, that are typically the most concerning. This is because radioactive elements that emit alpha particles such as radium can become airborne as dust, drift through the air or be blown about by the wind and easily be inhaled or ingested. Once inside the soft organ-filled space of your fluid body – or lodged in your bones – an alpha particle’s explosive charge can shred DNA to pieces, causing mutations in your genetic material that can potentially affect future generations and obliterate cellular structures, creating the possibility for the development of tumors that can lead to fatal cancers.

Brandon Novogradac: I guess to me it’s like, this wouldn’t even be a conversation if companies had been more up front about what they’ve known for decades.

Cause we had respirators out there at all times. You know, cause we were dealing with volatiles that you could filter out with these respirators, and if there were particles that were like alpha and beta emitters then it’d be nice to have the respirator on so we’d not be breathing these particles in. And we were not metering for alpha and beta emitting particles, so like, yeah that sucks. That’s really frustrating.

So if we had known, at all, that this was even remotely a possible issue, we would’ve had a policy in place to minimize our exposure so fast. And we probably wouldn’t have been back out there doing that until we did so…

Brandon Novogradac talking to Public Herald in Washington County, Pennsylvania. © Nina Berman for Public Herald

And as far as the disposal of the stuff, so that’s the other part of this, like you said, is the leaching from the landfill to the streams, I mean there’s so many breakdowns on that side of it that it’s hard to even know where to start and boy, we could really spread the blame out. But at some point what it comes down to with things like this is someone has to step up and do the right thing and make themselves be accountable, man or woman, because otherwise it’s just a circle of finger pointing and no change ever happens.

Radiation is one of those things where it’s kind of a good place, to draw the line between what should be, like, a moderate level of concern and a severe level of concern. I feel the same way about asbestos, actually, too. Cause once you breathe asbestos in your body…it’s going to keep doing damage for a long long time. So, these are sort of gifts that keep on giving, you know. Gifts that you don’t want.

But as a worker, though, it’s deeply disturbing that I’ve seen, since then, studies that point to… even without knowing whether or not it is going to cause harm, like the fact remains that we knew about it and the potential was there. So…just pretty cavalier to not at least advise the workers who were handling it. I mean, cause now it’s not just an environmental issue anymore. Now it’s like, this is an injury issue. This is when people start to get sued. You know, with stuff like this.

So yeah. No bueno.

Louisiana-Based Oil & Gas Radioactivity Attorney Stuart Smith: Who’s Got the Cojones?

Like Dr. Emily Caffrey and Dr. Jan Johnson, many health physicists in America have not dug into the data and added up the doses to show that this industry is endangering thousands of oil and gas workers, and may already have endangered thousands more. Countless numbers, and nameless names, because health physicists have failed to appropriately examine the issue. They have not raised the alarm bell. Instead it is left to the independent journalists, and quirky scientists, and industry workers with enough courage to go against a mountain of momentum of the most powerful industry on earth and blow the whistle…and it is left to the trial lawyers, the most hated scum of the earth — at least according to world’s richest industries that is. As like with Dark Waters, or Erin Brockovich, it is often their work that serves as the only way into justice. For in America, for better or worse, it all ends up in a court.

And when it comes to oil and gas radioactivity, an Erin Brockvich or Robert Bilott has not yet been nationally anointed, but when one finally is, it will probably be the relentless, occasionally crass, often charming, New Orleans-born attorney Stuart Smith. He tried his first oil and gas radioactivity case against Shell and Chevron in the Mississippi oilfields in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and has become one of the go-to lawyers nationwide on complicated radioactivity cases, and the most prominent lawyer in the field of oil and gas radioactivity. He wrote a book about it all that was published in 2015 called “Crude Justice” and he knows the oilfields of Louisiana and Mississippi like the back of his hand. But the Marcellus is new to Stuart. While Stuart was not prepared to go on the record, citing that he was still involved in sensitive cases in this field, he previously told me for a story published in April for the environmental investigative site DeSmog Blog,

“I have litigated several cases that showed that oilfield waste caused cancer. All the big majors have known about this for many decades. The regulators are obviously aware of it too, it’s just that they don’t have the political cojones to do anything about it.” And when it comes to the workers, being unknowingly exposed to radioactivity contamination by multinational corporations that know full-well, Smith explained–“These men are guinea pigs.”

And yet in our conversation with Dr Emilly Caffrey and Dr Jan Johnson of the Health Physics Society they repeatedly said the amount of radioactivity involved in oil and gas production was not enough to affect the health of the workers. When it came to dosage, which is a way to measure how much radioactivity the human body has taken in, they kept bringing up the number 10.

Emily Caffrey: You can’t tease out an association between radiation and cancer at doses below about 10 REM.

REM stands for Roentgen Equivalent Man and is one of the main ways of measuring the amount of ionizing radiation deposited in human tissue, or put more simply, a measure of how much radiation your body absorbed. So Dr. Caffrey gives us this magic number of 10, and yet from reading through the dose reconstructions in Stuart’s cases one sees that some workers measured cumulative doses estimated to be as high as 33,000 REM, and regularly in the range of 100 to 1,000 REM. But the tragedy is, a thorough dose reconstruction as laid out in Stuart’s cases has never been done for Marcellus oil and gas workers.

As Smith had told me earlier, for my Rolling Stone story published in January, They Know. “All of the big majors have done tests to determine exactly what risks workers are exposed to,” Smith said. “One question I ask these companies, what you have done to go out and find all the radioactive waste you have dumped all over the United States for the past 120 years. And the answer is nothing.”

Dr. Julie Weatherington-Rice: “They’re Going to Die”

What’s odd when you start to dig into the topic of oil and gas waste and radioactivity is that at first it seems to be this giant black box, and it is hard to find any information. And then suddenly you cross a certain threshold, you read the right paper, or click in the right Google search word combination, and suddenly you are deluged with prominent reports. And then you meet someone like Dr. Julie Weatherington-Rice, an earth scientist with the Ohio-based firm Bennett & Williams who has been studying oil and gas waste since she did her master’s thesis on the topic back in the late 1970s. In the 1980s she worked on a commission for Ohio’s governor that assessed the health risks associated with spreading oilfield brine on roads, and she has been on brine ever since. Her notes of easy-to-express concern, outrage, and grief were like coming across a clear-sighted oracle in a clearing, in the middle of a forest of regulators where everyone is speaking babel.

Julie Weatherington-Rice: Well, the salt itself will kill ya! The salt levels are terrible. Just being splashed by this stuff will cause all kinds of skin problems. Inhaling it in a vapor is very dangerous. You’ve got a number of volatile organic compounds and some have volatile organic compounds in it, the standard ones that you’re looking for are BTEX, which are benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, and xylene. But there are a whole slew of other ones as well that are included. They all have health regulations. And exposures to the levels in the brine are significant enough to be a demonstrated hazard. And the heavy metals, all the concerns of the health damage from the heavy metals – you’ve got barium, you’ve got lead, and you’ve cadmium, and you’ve got strontium, name every awful heavy metal that’s on the list, and I will tell you it’s there in some levels. So the things that you’re concerned about are the volatiles, the semi-volatiles, the heavy metals, the chlorides and sulfides are huge, and then as we’ve learned later – the radioactivity part.

The hazards are known. It’s just that nobody has been in a place to do anything about it because the industry is sacred. They’re getting Hail Mary passes, they’re sacred. And as long as they’re making the contributions that they’re making at the federal and state level, and as long as we’ve got the government that we’ve got, they’re going to continue to be successful. The only way we’re really going to turn this around is to vote everybody out of office that takes contributions from the oil and gas industry.

And what about the workers like Tom and Brandon, the pinballs stuck in the middle of the toxic machine? Dr. Weatherington-Rice does not mince words:

Julie Weatherington Rice: Yeah, yeah, they’re going to die. They’re going to die, okay? I mean my father died of chemical exposures. My husband’s father died of chemical exposures. We’ve had generations after generations of workers who have died from chemical exposures of all different kinds. And sometimes it’s gotten the attention of, you know, the CDC and NIOSH and folks like that and OSHA, and sometimes it has not. We have much better rules and regulations for a lot of industries than we used to have, but oil and gas and coal are the outlaws. So, in a general sense, we are much, much, much smarter about chemical exposure than we were when my dad was the health and safety officer in all the places he ever worked. But, you know, what was safe one year, the next year the safety level was 1000x lower. So all of the guys that he was with were all the canaries in the cages, and they all had the exposures – so they all died. And there was enough death that people woke up and decided they needed to do something about it, and that’s why we’ve got the rules that we’ve got.

Behind A Veil: The Health Physics Society

There are the workers like Tom and Brandon and people on the ground taking samples like Andrew and Marco – often with considerable academic expertise – and then there are the “Health Physicists.” Technically, they are a profession devoted to protecting people and their environment from potential radiation hazards. Or, as the banner on the website of the Health Physics Society notes, “specialists in radiation protection.” The Health Physics Society is a professional organization composed largely of state and federal radiation regulators and various independent and academic scientists.

The scientists we spoke to, Dr. Emily Caffery and Dr. Jan Johnson, repeatedly conveyed to us that they were speaking for themselves, and that their words did not represent the views of the Health Physics Society. Both health physicists say that it is important for workers to be protected and be informed about the materials they are handling, yet continue to stress that radioactivity levels in the oil and gas industry are not enough to endanger workers.

Justin Nobel, one of the authors of this article, put out an article earlier this year in Rolling Stone magazine, the result of a 20-month reporting and research effort that laid out the incredibly sloppy way the Marcellus oil and gas industry is handling radioactive materials and multiple different pathways of concern for workers, Dr. Johnson and Dr. Caffrey helped pen a Rebuttal promoted on the Health Physics Society website that stated the article had some “egregious errors” and boldly stated: “Radiological exposures at the levels experienced in the oil and gas industry are orders of magnitude below where any observable effects will occur.” Soon after our talk with Dr. Johnson and Dr. Caffrey, this rebuttal was retracted. In our conversation, when asked if they thought oil and gas workers should be treated as radiation workers, as workers in the nuclear industry or medical radiation scientists are, Dr. Johnson said, “No, I do not. They do not receive doses that would qualify them to be radiation workers.”

Jan Johnson: My concerns are primarily that oil and gas TENORM be managed appropriately, and in accordance with the science as, as we know it, and that the regulations reflect the science accurately. You know, you have to understand that radiation is all around us, it’s in the air we breathe, it’s in the soil we walk on, we are all exposed to radiation every day. We know what the effects are at higher levels, um, but we don’t see any biological effects at levels in the range of background, so those are the things we know.

Emily Caffery: Part of our purview as the Health Physics Society, and specifically the “Ask The Experts,” is to look for news articles, TV shows, Chernobyl, Bosch Season 6, things like that, that come out and respond to them, because when we read that article a number of us noted the, some of the errors in that article, and we feel that it’s our job within our purview to respond to inaccurate information and to put out correct information.

And yet, here is the problem – Caffery and Johnson were unaware of some pretty important research.

In 1982, scientists with the oil and gas industry’s massively powerful lobby, the American Petroleum Institute, put out a report entitled “An Analysis of the Impact of the Regulation of ‘Radionuclides’ as a Hazardous Air Pollutant on the Petroleum Industry.” The report assessed the radiation risks to workers and the general public from oil and gas development, determined that brine contained “biologically significant quantities of Radium 226 and Radon 222,” and concluded that the totality of radionuclides brought to the surface in oil and gas production “represent significant sources of internal exposure, primarily in the occupational environment.”

The report continued, “Radium 226 is a potent source of radiation exposure, both internal and external. Radon 222 and its short-lived progeny deliver significant population and occupational exposures to the upper tracheobronchial tree, while Lead 210 and its decay product contaminate much process equipment and can represent significant exposure to the bone in some occupational subgroups. Radon 222 and its daughters cause the most severe impact to public health.”

And then there was the 1990 report in the Oil & Gas Journal, one of the industry’s most prominent and well-respected publications, which stated that NORM contamination was “a potential health hazard to personnel” and “a possible public relations problem for the industry.” The report suggested that “NORM-contaminated sludges and other waste materials including contaminated vessels and equipment may have to be handled as low-level radioactive wastes and disposed of accordingly.”

Another article on oil and gas radioactivity, published in the Society of Petroleum Engineer’s well-respected Journal of Petroleum Technology in 1993, reiterated those concerns. In fact, the article begins with the following: “Contamination of oil and gas facilities with naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM) is widespread. Some contamination may be sufficiently severe that maintenance and other personnel may be exposed to hazardous concentrations.“

Then, just a few years ago, the prominent International Association of Oil and Gas Producers lobby put out a 67-page document on “Managing Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (NORM) in the oil and gas industry” which acknowledges that radioactivity risks to oil and gas industry workers are quite real.

“There are two ways in which personnel can be exposed to radiation,” the report states, “irradiation from external sources and contamination from inhaled and ingested sources.” An accompanying diagram features an illustrated oil and gas worker standing above an open pipe spewing radioactivity, and another worker standing alongside breathing it all in. Tiny alpha and beta particles are shown accumulating in their lungs and guts. It’s a scenario not so different than our brine hauler Tom described, eating his lunch while connecting his truck to a brine tank and waiting for it to load, or Brandon who had to peek his head into a frack tank with accumulated sludges at the bottom to check levels.

The International Association of Oil and Gas Producers report has even more worrisome news for oil and gas workers like Tom and Brandon. “Exposure to ionizing radiation, even at low doses, can cause damage to the nuclear (genetic) material in cells that can result in the development of radiation induced cancer many years later (somatic effects), heritable disease in future generations and some developmental effects under certain conditions,” the report states. In fact, the report repeatedly alerts that, “A reading greater than twice background levels is a positive indication of contamination, and should be handled as such.” Recall, now, what Brandon had told us: “Double background is almost nothing still in my mind.”

Regulators Refuse Comment on Reports About Radioactive Problems & Fracking

This examination of workers’ exposure on the job is not to call ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater – it’s an expedition through a theater crowded with sheaves of documents and heaps of experts saying that the whole city block has been slowly smoldering for 100 years.

Plenty of information exists saying that these oil and gas jobs have legitimate radioactivity exposure risks. The American Petroleum Institute knows it, the Oil & Gas Journal knows it, the Society of Petroleum Engineers knows it, the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers knows it. Somehow, the tens of thousands of workers on the ground in booming oil and gas fields like the Marcellus, workers like Tom and Brandon, somehow they don’t know it. And somehow our health physicists don’t know it either.

And it should be noted that their words matter more than perhaps they even know.

After the “America’s Radioactive Secret” broke, concerned residents in states like Michigan and Pennsylvania took the article to their state regulators worried about radioactivity risks from oil and gas development to workers and the public, and they received the Health Physics Society rebuttal in response. When Public Herald,cornered Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection chief media spokesperson, Neil Shader, at the Rachel Carson State Office Building in downtown Harrisburg and asked him about the article, he had this to say:

Joshua Pribanic: You know the new Rolling Stone story that came out?

Neil Shader: Mmm, yeah I looked over it.

Joshua Pribanic: Did anything in there…?

Neil Shader: I know that there are a number of inaccuracies and, I’m probably going to butcher their name, but the Society of Health Physics, recently published a multipage letter detailing those inaccuracies. So I know it’s a story out there, a lot of people have found inaccuracies with it.

Why are our influential health physicists so confident there are no harms? Where are they getting their data from? From the agency Neil Shader represents, the police-force charged with overseeing the oil and gas industry in the most radioactive shale basin in the United States – Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP). If radioactivity got away from the ‘handlers’ of public perception in the Marcellus, fracking might lose its social license the world over. The Health Physicists we spoke with knew PA DEP’s report on radioactivity from 2016 quite well, and it appears they rely upon it heavily.

It was a report put out in 2016 by the PA DEP called the, “TECHNOLOGICALLY ENHANCED NATURALLY OCCURRING RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS (TENORM) STUDY REPORT.” This was intended to be the authoritative examination of Marcellus oil and gas radioactivity risks. PA DEP looked at the wellhead, they looked at the brine, they looked at the landfills, they considered workers and the public. And the report’s conclusion has been repeated time and again by the DEP, regulators in other states such as North Dakota, by the EPA in a 2018 report that examined Marcellus oil and gas waste streams, and even by FERC, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, in making critical calculations enabling the approval of fracked gas pipeline projects. The parroted conclusion is, “There is little or limited potential for radiation exposure to workers and the public from the development, completion, production, transmission, processing, storage, and end use of natural gas.”

Justin Nobel: So you regard the Pennsylvania TENORM Report as a good standard and as something with appropriate and accurate information?

Emily Caffery: Yes.

Jan Johnson: Absolutely.

But if you take the time to read the full TENORM report, you will see on the very first page that it was prepared, not by the Department of Environmental Protection, but by Perma-Fix Environmental Services, which is a radioactive waste management and cleanup company profiting from the industry’s waste.

The TENORM study pointed out that leachate from municipal landfills accepting oil and gas waste was accumulating radioactivity. Discharges to the environment were found at levels higher 100 times greater than what’s considered safe for drinking water (5 pCi/l). It also found that some privately owned treatment plants had radioactivity in soil at levels more than 100 times what would be acceptable for federal regulations at uranium mill tailings (5 pCi/g). Furthermore, the report states that some members of the public and workers are indeed at risk:

From the 2016 TENORM report:

“There is potential for internal radiation exposure to workers and members of the public from alpha and beta surface radioactivity at [centralized wastewater facilities] that treat O&G wastewater.”

“There is potential for internal alpha and beta surface radioactivity exposure to workers and members of the public at [zero liquid discharge facilities] that treat O&G wastewater.”

“There is potential for exceeding public dose limits from external gamma radiation for workers at the natural gas processing plant.”

After speaking with Marcellus oil and gas workers, it is abundantly clear that the DEP TENORM report does an incredibly superficial job of calculating radioactivity exposures, calculations to which these workers have attached their lives.

When it came to calculating doses, the DEP TENORM report makes no mention of measuring the dose received when workers had to stick hands or whole heads into tanks of sludge, or when workers climb inside tanks with shovels and squeegees to scoop sludge for up to an hour. Tom described one worker whose only job was tank cleaning, partly because he was a gung-ho young guy at the low end of the stick, and partly because he was so good at it.

When it came to calculating doses, the DEP TENORM report also makes no mention of workers eating their lunch in a dusty, sludgy workplace environment with unwashed hands, as Tom described to us. There’s no mention of having to clean up brine spills with inappropriate gear, as Brandon described to us, and no mention of brine splashing on their faces and into their mouths during flowback operations, as Tom described.

And yet, workers and the public hear the rhetoric about this report on repeat ‘All is fine, no risks here,’ from industry experts and state officials when faced with concerns.

Here is Neil Shader again, the spokesman for PA DEP:

Neil Shader: We take environmental health and public safety very seriously.

And here is Scott Perry, the Deputy Secretary of the Oil and Gas Division of PA DEP:

Scott Perry: I think that Pennsylvania is very progressive when it comes to managing TENORM.

This is what Marcellus oil and gas workers hear when they express concerns and what journalists have regularly been told about the topic. Perhaps most significantly, this is what state representatives who draft the laws that claim to protect its workers and the public, have regurgitated ad nauseam.

When we asked Pennsylvania state senator Camera Bartolotta, who represents a district in the booming heart of the Marcellus in Washington County, Pennsylvania, about oil and gas radiation, her office replied:

“Senator Bartolotta took the initiative of reaching out directly to industry to understand better how they are managing risks from TENORM…

“DEP comprehensively studied this issue in cooperation with other public and private organizations and determined that NORM and TENORM materials associated with the oil and gas Industry were well managed and did not present a risk to the public. It found that while the majority of waste streams generated by the oil and gas industry did not pose a risk to workers or the general public, industry professionals were able to make proper adjustments to handling, processing, and disposal protocols based on screening, monitoring, and analytical data.”

Everywhere we turned, PA DEP’s report was referenced to dispel concern, a report produced by a company connected to the industry, branded as official by the state’s department of environmental protection, and treated as the gold standard. And yet, all the while, the workers whose well-being everyone claims to be so concerned about, are left out in the cold, woefully misinformed, tragically and unnecessarily exposed.

Landfills and Wastewater Treatment Facilities: The “Asshole” of the Industry

I am back with Brandon at the foot of Arden Landfill in Washington County, Pennsylvania, otherwise known as Mount Trashmore. From 2011 to 2018, 1,297,000 tons of solid waste generated from Pennsylvania oil and gas wells were disposed of at Arden Landfill, and 99 percent of that came from fracked wells in the Marcellus shale, which, according to the best U.S. Geologic Survey reports and data, appears to have a radioactive signature higher than any other oil and gas play in the country – the agency, by the way, has known the Marcellus was highly radioactive for at least 60 years.

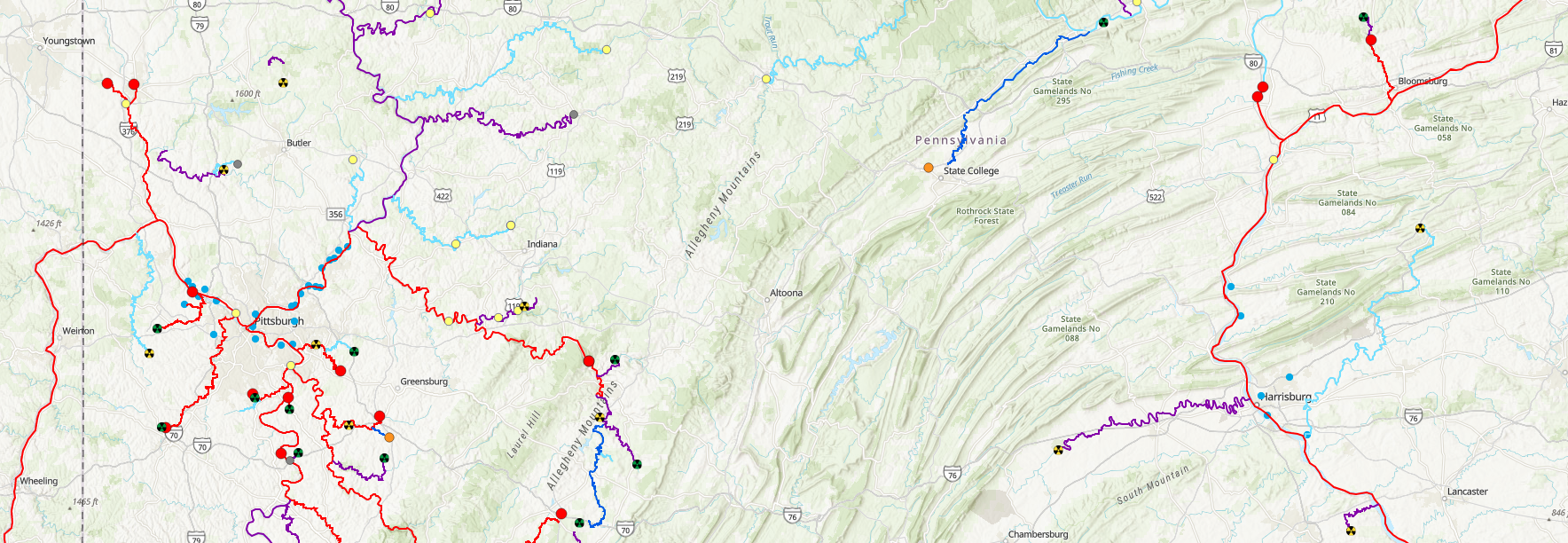

Public Herald’s TENORM Leachate Map illustrates where (in red) TENORM from fracking is escaping into public waters, and where (trefoil symbol) it’s being stored in Pennsylvania. Click for interactive map »

According to Public Herald’s investigations Pennsylvania has 30 landfills accepting oil and gas waste who send their leachate to sewage plants, subjecting millions of people who live downstream to exposure to radionuclides. So you see, this is affecting a lot more than just the workers. The public is at risk too. Landfills and the sewage treatment plants that are supposed to treat their leachate are, as Guy Kruppa, a sewage treatment plant operator in Belle Vernon Pennsylvania and one of of our first whistle-blowers on this topic revealed to us, like “the assholes of the fracking industry.” Because after being upchucked to the surface during the production process, and shuffled around the various intestinal tubes and organs of the industry’s storage and hauling and treatment processes, this is where so much of the solid waste ends up. Our experts did not take lightly to this unfolding disaster:

Andrew Gross: Putting this radioactive material into municipal waste sites is a giant concern. That could be life-altering for a lot of people, people in the vicinity, people downwater of streams, all those things.

Julie Weatherington-Rice: This is a permanent reactor. Near your house. And it will always be a reactor. Because the waste got pooled together. And it will make as much radon and radium today as it will tomorrow and the next day and the next day and 30 years from now and 100 years from now and 500 years from now. Because the half life of this stuff is like, forever. The half life of uranium 238 which is in the cuttings in 4.47 billion with a b years old. And the thorium is 14 billion. That’s like back to the big bang. So while it’s a naturally occurring material, when you concentrate it, you create a reactor.

Marco Kaltofen: Well we’re going to go to that dark place again. If you think about what a landfill is think of it as the world’s worst tea bag. You have waste sitting in the landfill and the rain water percolates through, and the leachate is that rain water coming out after it’s been through the tea bag, after it’s been through the landfill. And it has all this yucky stuff in it. And you try and get rid of it by sending it to the local sewage treatment plant – which treats waste in a really old fashioned, simple, fairly effective way, they throw all the stuff in a great big vat, like acres and acres of vat, and they just let the bacteria eat it. And the bacteria get really fat and sink to the bottom and that’s our sewage sludge – all that dead bacteria. Hey our bodies do that too – 25% of our solid waste is bacteria. So, the sewage plant is basically us you know on a giant scale. And then you cart that sludge back to the where else? The landfill. Where the rain water percolates through and the cycle continues. But if you do it enough times you know that tea bag that’s really gross, the leachate gets worse, and the treatment plant can’t take it anymore because the stuff would actually kill the bacteria that do all the work. And so not only is your waste from the landfill not treated. But none of the waste from the entire community is treated. It’s like an amplifier. You shut off treatment for everybody. So you can’t take the leachate anymore. So what happens to the leachate? Ah! There’s a trick! You take the leachate and throw it back on top of the landfill, and let it percolate through again and it’s like The Sorcerer’s Apprentice if you ever saw the Mickey Mouse cartoon, where you’re collecting more leachate, so you throw it on top of the landfill so more leachate comes out the bottom, and this goes faster and faster and faster. And you’d think it’s entirely stupid but what you’re forgetting it’s while that’s happening – everybody is getting paid. So the system continues. Really we’re not making treatment systems for radioactive waste, we’re making transit systems. You know, we’re moving them from one place or one medium to another without actually dealing with the problem at hand.

And yet the DEP continues to tell us there is no problem.

Back to when Public Herald tried to speak to DEP Spokesman Neil Shader in Harrisburg about this radioactivity issue. Speaking is Joshua Pribanic, the co-founder of Public Herald.

Joshua Pribanic: I hate to be this way with you, but we’re telling you you’re informed about the radioactive leachate story, we’re telling you you’re informed about those other places. Get out there, get somebody out there, and test it. And start issuing the enforcement, start issuing the violations. You know, it’s not a difficult thing to do, we did it in less than a month’s time. With very little money.

Neil Shader: Our staff are out there. We take compliance very seriously. That’s our overarching goal.

Joshua Pribanic: What do you think I wanna do? Write about radioactive leachate for two years? You know that’s the situation you guys are putting us in. You guys are not going out there and handling these stories. I should’ve ended that story after we published it. But now we have to continue it for another year because there’s no enforcement, no action. I gotta go out and do the testing for you? I mean, that’s what we’re dealing with. As a news organization. So it’s frustrating for us to be in this position, where we’re learning all this information. The same information you have. In most cases we’re just publishing your documents. We’re publishing your TENORM study that says the POTWs are hot. There’s a TENORM study that you have, from PERMAFIX, and it says right in there, you have a long term problem, a chronic problem, of radioactivity building up, in picocuries per gram, in the soil and in the stream bed that is outside of the sewage plants. And here we are, three years later after that study, nothing done about it.

Neil Shader: Alright, well, good talking with you guys.

The Path Forward