America Is Building Mountains of Radioactive Fracking Waste & the One in Joe Biden’s Hometown Is Under Criminal Investigation

America Is Building Mountains of Radioactive Fracking Waste & the One in Joe Biden’s Hometown Is Under Criminal Investigation

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

SUPPORT newsCOUP

Public Herald is a nonprofit newsroom that holds those in power accountable. You can receive our latest breaking stories by subscribing to our newsletter or becoming a Public Herald Patron.

by Emma Lichtwardt and Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald, edited by Melissa A. Troutman

June 1, 2021 | Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers, TENORM Mountains

update 4:08 p.m. June 1, 2021: a comment from the landfill manager Magnotta who denied taking in fracking waste was added as well as a response to his characterization of “drill cuttings” and radioactivity.

update 3:47 p.m. June 3, 2021: DEP announced June 3 that it had approved the application for the Keystone Sanitary Landfill’s expansion, allowing for a 435-acre expansion and increasing its disposal capacity by 145 million cubic yards.

DEP’s announcement says the expansion modification (i.e., the permit) contains “specific conditions that are protective of public health, safety, and the environment.” Public Herald’s investigation on Keystone in this article conflicts with DEP’s statements about public health and safety.

Correction update 1:51 p.m. June 14, 2021: Roger Bellas was incorrectly cited in this report as having worked for Keystone in the past. Bellas has never been employed by a landfill (including Keystone Landfill) or any other waste disposal operation in a response emailed from DEP. Mr. Bellas has been with DEP since 1994, and has been DEP’s Waste Management Program Manager since 2014.

Pennsylvania’s Largest Fracking Waste Landfill is Under Criminal Investigation for Dumping Radioactive Leachate

A community group’s letter about a landfill accepting fracking’s radioactive waste caught the attention of the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Environmental Crimes Unit.

In the heart of President Joe Biden’s hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania, the Friends of Lackawanna are fighting the massive expansion of Keystone Sanitary Landfill, a waste dump that accepts radioactive material created by fracking for oil and natural gas.

“This is the future of our community at stake,” said Michele Dempsey from Friends of Lackawanna. “Our community lives or dies on this [expansion] decision, and so we gave it our hearts and souls.” Dempsey’s community is just one of many across America where, since fracking began, state and federal regulators have sent radioactive material to residual waste sites. As this waste piles up in public and private landfills, the size and risk of these “TENORM Mountains” looms large.

caption: USA, Pennsylvania, June 17, 2020. Michele Dempsey and Sam Maloney of Friends of Lackawanna stand together (Michele is in black) with the Keystone Sanitary Landfill in the background. The Landfill is requesting an expansion that would make it the largest geographical feature in the area. © Nina Berman for Public Herald

When Dempsey returns home from her office in neighboring Dunmore Borough after a demanding day of work, relaxing is far from her mind. She sits down, pulls out her laptop, and begins research for what she considers her “second job.” Across town, Sharon Cuff and Samantha Maloney are doing the same. Their jobs and routines are winding down for the day, but their second life unfurls here each night in front of computer screens and phones to find out, “Has a landfill expansion ever been stopped? If so, how?”

In Dunmore, according to resident Sharon Cuff, three new anti-landfill candidates were newly elected in the May 2021 primary: Mark Conway (Mayor), William O’Malley (City Councilor) and Katherine Oven (City Councilor).

Dempsey, Cuff, and Maloney are part of Friends of Lackawanna, a non-profit group dedicated to protecting the health and safety of Lackawanna County from a proposed 165-foot vertical expansion of Keystone across 435 acres, which includes a 145-million cubic yard capacity increase. Any day now, the expansion could be approved by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), dramatically increasing the amount of radioactive material from fracking waste accepted at Keystone until it becomes higher than the Statue of Liberty.

caption: A view of the Keystone Sanitary Landfill (in the background) from a residential street. © Nina Berman for Public Herald

Keystone has a dirty history of contaminating groundwater, alleged illegal dumping, and other faulty operations that have led to federal investigation and litigation. The latest is its trouble with landfill leachate, the contaminated liquid that leaches out of landfill debris after rainfall.

In December 2020, Keystone was punished by the DEP for contaminating groundwater with leachate and for storing it above regulatory limits, in violation of the Solid Waste Management Act. But records reviewed by Public Herald show that during the leachate investigation DEP did not require radiological testing of the leachate, despite outcry from Friends of Lackawanna.

According to public records, the community around Keystone has complained to the DEP about problems at the landfill 224 times since 1987. Yet, not one citizen complaint in 34 years has resulted in a violation enforcement or penalty from the Department. Public Herald’s decade of research and reporting about DEP complaint investigations has never revealed any other case where all of a community’s complaints about a particular facility or company resulted in zero enforcement actions.*

Radioactive Rainwater — When Protectors Don’t Protect

Radioactive material within the fracking waste buried at Keystone and other landfills is water soluble, which means that when it rains, radionuclides like cancer-causing radium-226 end up in landfill leachate. After receiving little help from Pennsylvania DEP about radioactivity and other concerns, the Friends of Lackawanna stopped hearing from DEP all together. So the group reached out to their District Attorney, who referred them to the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Environmental Crimes office.

“Due to the Department of Environmental Protection’s lack of response, I am turning to your office,” wrote Sam Maloney in a letter addressed to the Lackawanna County District Attorney. Referring to an alleged leachate dumping incident at Keystone in September 2016, Maloney’s letter seeks “to refer this matter to the Attorney General’s Office for a full investigation” of the “harmful effects on the air quality, safety and health of the citizens of Scranton, as well as the water quality of Meadow Brook Creek and the Lackawanna River.”

The City of Scranton and the Borough of Dunmore have also written letters to Roger Bellas, the Waste Management Environmental Program manager for Pennsylvania DEP. Bellas is now a DEP state authority in Keystone’s expansion process and has handled all public comments on the matter. Letters from both municipalities express growing concerns about the impacts of the Keystone expansion project.

In November 2019, Friends of Lackawanna received notice from the Lackawanna County District Attorney’s office that the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office had assumed jurisdiction over the Keystone Sanitary Landfill leachate case.

PA Attorney General Josh Shapiro’s office confirmed in a statement to Public Herald that it has an open investigation into Keystone, but wouldn’t comment further. The AG’s office would neither confirm nor deny reports about a second investigation about the Technically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (TENORM) from fracking waste that Keystone has accepted. DEP, when contacted by Public Herald, had no comment and redirected Public Herald to the AG’s office.

Caption: Maloney’s letter has kickstarted an ongoing investigation by the Environmental Crimes unit under acting AG Josh Shapiro.

While the involvement of the AG’s office has been encouraging for some, there’s no promise of full accountability. The AG’s multi-year investigation of Pennsylvania’s management of fracking resulted in charges against oil and gas companies, but the misconduct by state officials, while admonished, did not lead to indictments.

During a May 25 press conference with Attorney General Shapiro’s office, Pennsylvania State Senator Katie Muth responded to Public Herald’s questions about DEP’s accountability. Muth, when asked what would be done to hold the DEP accountable, expressed concern over the DEP’s mishandling of the industries it’s supposed to regulate.

“I certainly think the DEP better, you know, put up or shut up because they say they’re here to protect,” Senator Muth said. “We the People pay the salaries for every government official, right? And so, their job is supposed to be to protect us and the environment. If you can’t do your jobs, then you’ve got to go.”

To date, very little information about the Keystone case has been released to Friends of Lackawanna from the AG’s office. But local sources say they’ve met with the AG’s investigators about Keystone’s leachate issues, including ones uncovered in Public Herald’s radioactive leachate investigation. Maloney explained that after two meetings with the AG’s office — the most recent at the end of April — she’s confident the Office is at least aware of and listening to their concerns. For Malony, it sends a message when the AG’s staffers know “what leachate is.”

But the clock is ticking for Friends of Lackawanna — everyday they wait to hear if DEP has approved Keystone’s expansion.

All of the following officials, organizations, and schools have openly opposed the Keystone landfill expansion: The Dunmore City Council, Dunmore Mayor Tim Burke, Scranton Mayor Paige Cognetti, Scranton City Council, Mid Valley School District and Board, Scranton School Board, Pennsylvania Representative Kyle Mullins, U.S. Congressman Matt Cartwright, U.S. Senator Bob Casey, CFHJ & PA Sierra Club of Lackawanna County, and the Sierra Club.

Little Federal Oversight

On the national level, President Biden’s climate plan neglects the impacts that fracking’s oil and gas waste has on towns like Scranton and Dunmore – waste that will be produced for decades even after fracking ends. Biden’s climate plan fails to close gaping loopholes for the oil and gas industry that have existed since the 1980s, when the federal government exempted the industry’s waste from hazardous waste law. This creates the opportunity for landfills like Keystone, which are not officially authorized to handle hazardous waste, to continue accepting large amounts of radioactive, potentially hazardous material from oil and gas operations.

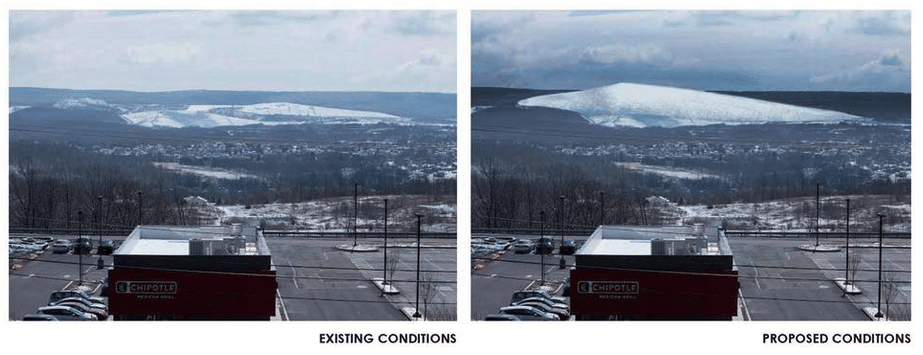

The approximate size of the Keystone Landfill if DEP approves its expansion. Photo via Friends of Lackawanna

If Pennsylvania DEP approves Keystone’s proposed expansion, the landfill’s ability to operate will be extended until 2064, allowing thousands more tons of radioactive material from continued fracking development to be trafficked to the town where Biden grew up. This would make Keystone a new landmark – the landfill will become the tallest geographic feature in the area.

America is Building TENORM Mountains

Everyone knows that oil and gas wells produce oil and natural gas. But few people understand that these wells also produce radioactive material, or that this material is being disposed of in community landfills alongside household trash, as it is at Keystone.

Washington County, Pennsylvania: Arden Landfill looming above Washington County Fairgrounds in January 2020 after more than a decade of accepting fracking’s TENORM waste. Arden Landfill, or Mt. Arden, accepted 1,297,000 tons of solid waste generated from Pennsylvania oil and gas wells between 2011 and 2018. Credit: Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

Oil and gas waste materials contain TENORM (Technically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material), although some states simply refer to it as NORM (Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material). Essentially, what starts as naturally-occurring radioactive material (NORM) contained deep beneath the Earth’s crust is brought to the surface by human activities, such as fracking, to create TENORM. These processes can raise concentration levels of radioactive materials throughout operations and increase exposures to workers and the public.

One of the main radioactive elements in oil and gas TENORM waste is radium-226, an alpha-emitting isotope with a half-life of over 1,600 years that is known for its ability to cause cancer.

Though oil and gas waste contains hazardous materials, it’s not considered “hazardous” by the EPA. In 1988, the EPA declared that even though oil and gas waste contains toxic heavy metals, carcinogens, and radioactivity, regulating the waste as “hazardous” would cause “a severe economic impact on the industry and on oil and gas production in the U.S.,” so it exempt the industry from hazardous waste law under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).

TENORM from oil and gas operations is also not covered by federal regulations governing radioactive material, including the Atomic Energy Act.

Radium from TENORM appears in high concentrations for several types of oil and gas waste, and the detections are higher for fracking waste streams that include sludge, drill cuttings, pipe scale, wastewater, and used equipment. According to radiation expert Andrew Gross, oil and gas workers have also transported TENORM into their homes, exposing their families to radioactivity they picked up on the job. Pennsylvania DEP’s own TENORM study from 2016 cites the same risks to workers if operations continue unabated.

caption: DEP’s 2016 TENORM study (prepared by PermaFix) explaining how TENORM can be a risk to workers at sewage authorities.

The problem for communities (and watersheds) in the United States is that TENORM is piling up within landfills like Keystone across the country, and not just in fracking regions like Pennsylvania. The federal exemption for oil and gas waste means that fracking waste can be imported across state borders, sometimes to states where fracking is restricted – like New York State — or to where it’s just not viable, like Montana. (Join Public Herald’s Patreon for upcoming talks about TENORM in other states.)

Never before in the history of America has the country undertaken such a radioactive experiment, bringing massive amounts of carcinogenic material to the surface and depositing it inside populated areas.

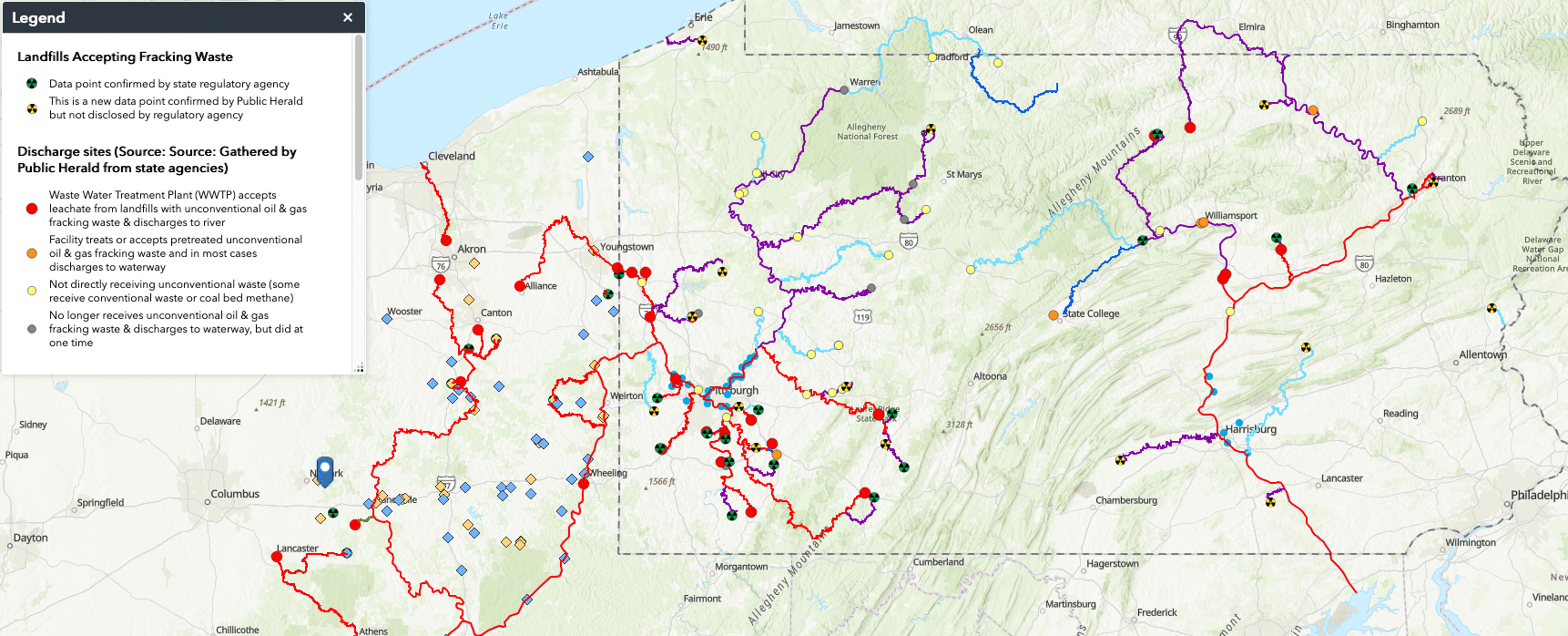

caption: Public Herald’s TENORM Leachate Map illustrates where (in red) TENORM from fracking is escaping into public waters, and where (trefoil symbol) it’s being stored in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Click for interactive map »

Keystone’s Expanding Impacts on the Community

Keystone Landfill divides the city of Scranton and the Borough of Dunmore. It is a half mile from the nearest residential area and 1.7 miles from the Dunmore School District. Keystone is also only 800 feet away from a Dunmore reservoir, which serves as an emergency drinking water source and popular recreation area.

In addition to Keystone accepting rocky drill cuttings that can contain TENORM, the landfill was cleared by the DEP in 2014 to also accept drilling fluids from fracking sites. The liquid waste from fracking has particularly high levels of radium-226. DEP’s 2016 TENORM study found high levels of radium-226 in both conventional and unconventional oil and gas wastewaters. Every wastewater sample in the study exceeded the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) limit of 5 picocuries per liter (pCi/L) for combined radium in drinking water — some radium-226 levels were as high as 26,600 picocuries per liter (pCi/L) in the wastewater from fracked gas drilling sites.

For the Friends of Lackawanna, all of these concerns about Keystone could have ended in 2015, when the landfill’s Waste Management Permit was set to expire. This would have required that the landfill be closed and capped for good, which residents were eagerly awaiting. But before its time was up, Keystone submitted an application to the DEP Bureau of Solid Waste for an expansion to allow for an additional 125 million tons of waste, adding almost a half-century more disposal to what could become the state’s largest trash mountain.

caption: A before and after rendering of the view from a home in the Swinick development of Dunmore, PA shows the projected view of the Keystone Landfill post-expansion. Photo via Friends of Lackawanna

When Dempsey first heard about the expansion project “The blood boiled in my body,” she told Public Herald, “and I just couldn’t shut up about it. Anybody who would listen to me, I talked to.”

Keystone has since been identified by Public Herald as one of 30 Pennsylvania landfills accepting fracking waste and producing leachate that’s making its way into public waterways.** Some of these facilities were never mentioned by the DEP when Public Herald first asked the agency for a list of all Pennsylvania landfills accepting fracking waste.

Under Pennsylvania law, landfills can send their fracking-contaminated leachate to wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), like local sewage facilities. Oftentimes, these treatment plants are not equipped to properly eliminate radioactive material before dumping their effluent into rivers. The result is a statewide system that can discharge radioactive residuals from fracking into waterways from at least 18 WWTPs across Pennsylvania — including the Scranton Sewage Authority, now Pennsylvania American Water Company, which accepted leachate from Keystone for years.

But in 2019, Keystone began doing something different — it got approval from the DEP to operate its own on-site leachate treatment systems. Keystone installed a reverse osmosis treatment system and obtained permits allowing it to discharge treated leachate directly into two streams that run alongside the landfill (Eddy Creek and Little Roaring Brook), in addition to sending it to the Pennsylvania American Water facility in Scranton, which discharges into the Lackawanna River.

According to a 2016 letter from DEP, Keystone would be restricted to releasing only 1 pCi/L of combined radium 226 & 228 since “the facility accepts fracking waste.” However, a final permit for Keystone to discharge waste into waterways (sent to Public Herald from DEP in May 2021) does not list a limitation for radium.

PA American Water’s discharge permit also does not require monitoring for radium. When asked by Public Herald whether TENORM would be considered in the expansion permitting process, the DEP provided a written statement saying, “TENORM is material that is taken into consideration and analyzed when DEP reviews permit applications, including a permit application regarding landfills.”

But Marco Kaltofen, an expert who traces where radiological substances end up over time and whether they’re disposed of correctly, told Public Herald, “We’re not making treatment systems for radioactive waste, we’re making transit systems. We’re moving [it] from one place or one medium to another without actually dealing with the problem at hand.”

“Radioactivity was created when the earth was formed millions of years ago, and a few hours [of treatment] in a public treatment plant isn’t going to make much difference,” Kaltofen says. “It’s a web of added radioactivity, and so far, we’ve only figured out how to spread it, and we haven’t figured out how to really treat it.”

TENORM Speculation & Lack of Regulations

The Department has always known about TENORM problems from oil and gas waste. In 1991, DEP released a study on [TE]NORM in oil and gas development that pointed to a need for state regulations and restrictions. But, no one took serious action.

Today, all landfills like Keystone that accept TENORM waste from fracking operations can use it to cover trash at the landfill. For the last decade, DEP has been allowing, even promoting, this “beneficial use” of oil and gas waste as a way to prevent trash from blowing off the site.

The state’s 2016 TENORM study made it clear that, “Because landfills accept natural gas industry wastes such as drill cuttings and treatment sludge that may contain TENORM, there is a potential for leachate from those facilities to also contain TENORM.” In the study, all of the testing conducted by the state of landfill leachate showed evidence of TENORM.

In an article from The Times-Tribune published May 20, 2021, about the AG’s investigation into Keystone it quoted landfill consultant Al Magnotta as saying that there is “absolutely no fracking waste in Keystone” and that the well drill cuttings accepted by the landfill are not at all related to fracking. Magnotta’s statement uses a game of semantics that drill cuttings are not the same as “fracking waste” — though the drill cuttings are a waste product sent to Keystone from fracking operations in the state.

“We do not take [fracking waste] … Anybody who says we do is just absolute freaking nonsense,” Magnotta was quoted by The Times-Tribune as saying.

Keystone is authorized to accept up to 7,000 tons of waste per day, and DEP approximates that 700 tons of TENORM-laden drill cuttings are disposed of at the Keystone landfill per day. Again, DEP’s study reported TENORM detected in every drill cutting sampled.

caption: DEP’s study of TENORM in oil and gas drill cuttings, like the ones dumped at Keystone, show levels of radionuclides in cuttings from vertical and horizontal well bores.

A Keystone Sanitary Landfill Health Consultation published by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry said it found, “At a site visit in 2015, landfill management characterized the composition of accepted waste as approximately 77% municipal solid wastes, 10% drill cuttings from unconventional natural gas drilling operations, 6% sludge and residual wastes, 4% flood wastes, and 3% construction and demolition wastes.”

Dempsey says the cumulative effect of TENORM disposal at Keystone has never been studied. She asked landfill representatives at a town meeting if they had any idea what the cumulative effect might be of radioactive disposal at Keystone, “They had no idea,” she said. The 2016 DEP TENORM study sampled landfills, but did not disclose which ones.

So exactly how much TENORM is accumulating at Keystone? No one really knows for sure. All the waste is supposed to be checked for TENORM, but DEP-required monitoring at the landfill has been criticized by experts like Dr. Julie Weatherington-Rice, who says: “Pennsylvania is counting on smoke and mirrors for protection because they’re not using the right test, and they’re not using the right equipment.”

John Mellow, who worked at DEP for 30 years in the hazardous sites cleanup program, said that after working for DEP, he’s troubled by the agency’s handling of Keystone and wants to see firmer data if DEP is going to claim Keystone isn’t causing environmental and health problems.

“My issue is not to cry, ‘The sky is falling,’ but to make sure that there’s actually data to show that there’s no problem, not just speculation as DEP has done,” Mellow said.

Residents Question TENORM Exposure

In the past, Keystone sent a maximum of 150,000 gallons per day of leachate to the Scranton wastewater treatment plant.

Experts have told Public Herald that the treatment methods used onsite at sewage facilities are not equipped to remove TENORM from landfill leachate. There is logical reason to believe that for the past six years or longer, the Scranton sewer authority could have been releasing TENORM from Keystone Landfill into public waters through the sewer system, even if the leachate was “treated” – especially considering the facility’s discharge permit does not include monitoring for TENORM.

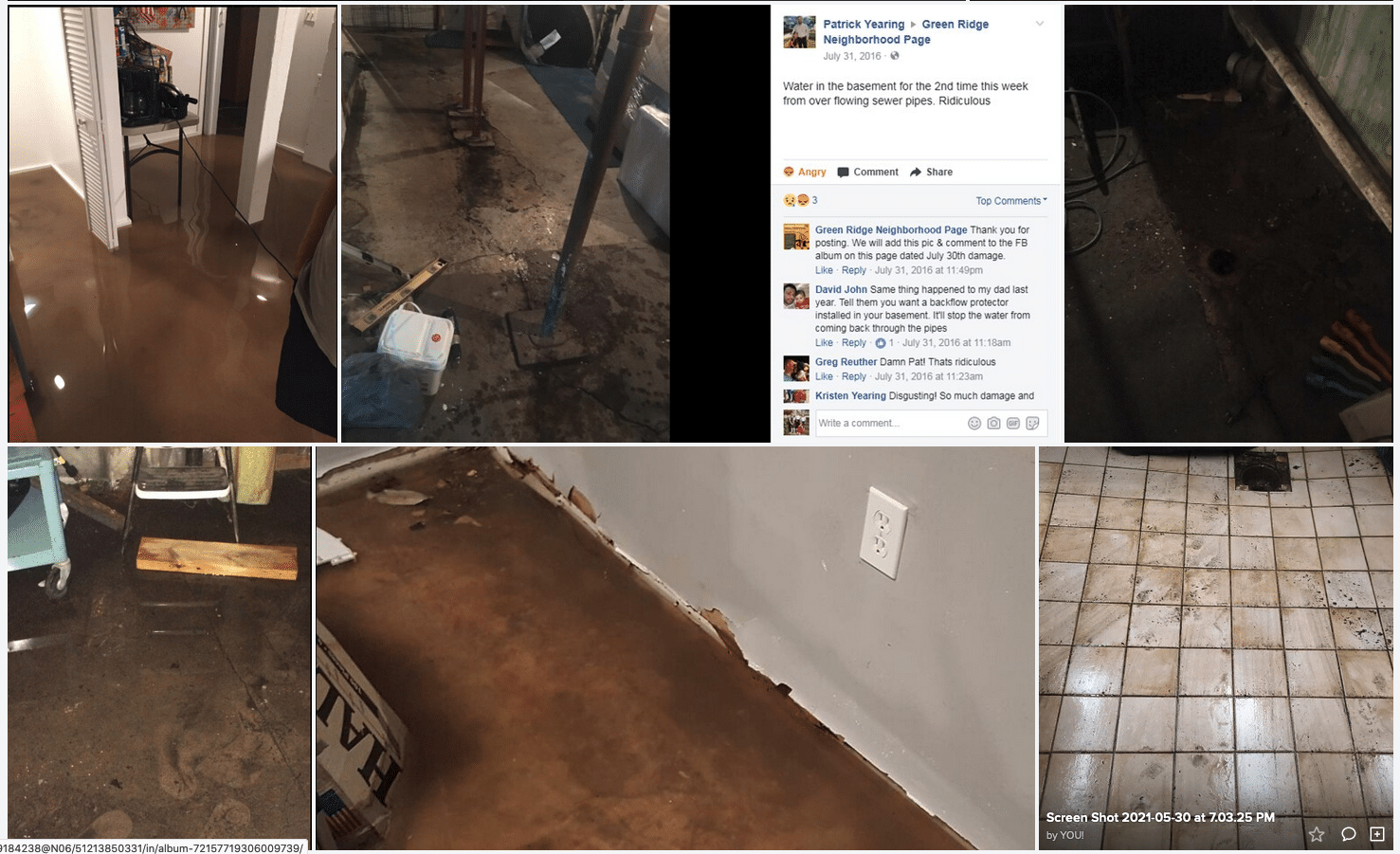

“If [radium] is water soluble and it’s coming through an archaic sewer system, it exposes all of us,” Maloney told Public Herald. “If it’s rainy and there’s an overflow, it’s coming into, at a minimum, Meadow Brook Creek, and moreover, it could be coming directly into our houses.”

“Do the citizens of Scranton whose homes have been flooded from discharge from their drains have radionuclides in their homes? Is leachate mixed in with this? How dangerous is this to us?” asks Maloney.

caption: Homes in the Keystone area that were flooded from combined sewage overflow after heavy rains. Keystone has been accused of illegally dumping their leachate down the sewage outfalls. Photos provided by Friends of Lackawanna

Senator Muth, when asked by Public Herald how the state would deal with it’s radioactive leachate problem, referred to the permitting of landfills to dispose of the radioactive leachate as a “loophole in the law” that needs to be addressed. Part of the problem, Muth said, is that the DEP won’t provide the state with stable, reliable data on how many landfills accept the waste.

“This is almost like organized crime … I don’t know how else to explain why this is happening. I don’t think this is gross incompetence anymore,” Senator Muth said to Public Herald after seeing Public Herald’s previous reporting on the DEP’s failure to report 17 landfills and four WWTPs accepting and discharging TENORM-laden leachate. “It’s an epic failure of a government entity that is funded by taxpayers … You can’t say you’re doing your job and everything is fine if you’re not even sure where this stuff is being discharged, you’re not even sure where it’s being dumped.”

Senator Muth said she’s “confident” that the Attorney General’s office is looking at the issue.

Keystone Denies Illegal Dumping

On September 26, 2016, a strange smell enveloped Dunmore. The odor was so foul, it required the complete 3 a.m. evacuation of a local hotel and St. Joseph’s, a center for medically fragile and severely disabled adults.

“People said they couldn’t sleep, they couldn’t even be in their houses,” Dempsey recalls. “It was just that terrible. The landfill general manager admitted that night that they were running leachate down the line. But the next day, they retracted that statement and said it was all a mistake.”

The Scranton-based Times-Tribune reported that Keystone’s consulting engineer, Albert Magnotta, claimed that the liquid causing the smell was not treated leachate from Keystone. However, the day the odor was detected, Magnotta said, the landfill had discharged treated leachate through an emergency line through the Green Ridge neighborhood due to maintenance on a pump in the facility.

During storm events when the sewer is full, excess waste is sent through a combined sewer overflow (CSO) called Outfall 2. Most modern sewer systems collect stormwater separately from sewage wastes to prevent overflow problems. However, in antiquated systems like the one being used by Keystone and the Sewer Authority, these two waste streams are still combined, which has led to problems for local residents. According to Friends of Lackawanna, stormwater runoff, sewage, industrial stormwater waste, and Keystone’s leachate all go directly into the Lackawanna River via Outfall 2, avoiding any treatment by the Scranton Sewer Authority (Now owned by Pennsylvania American Water Company).*** The Scranton Sewer Authority claimed to Public Herald in a recent email that it is “in no way connected to the Keystone Landfill” and “would have no comment.”

caption: A document citing up to 150,000 gallons of Keystone’s “treated” leachate being sent to the Scranton Sewer Authority per day.

The Green Ridge Neighborhood Association filed a lawsuit against the Scranton Sewer Authority — which in the next year would be sold to Pennsylvania American Water — regarding the sudden permit amendment allowing the use of the previously unapproved Outfall 2. In 2016, the case was dismissed after too much time had passed with no action.

Friends of Lackawanna says the agencies whose duty it is to help citizens answer difficult questions are providing next to no help, specifically the DEP. They have been asking difficult questions on behalf of their community and its safety for the past six years and speculate that the DEP may not be adequately staffed to handle the problems that the landfill is producing.

“They can’t handle everything that is being thrown at them, so [DEP] just believes what the landfill says,” Sharon Cuff stated, “so maybe it’s staff cuts or lack of hands, but that is not our fault. We are the community they are here to protect, and they won’t help us.”

The Friends of Lackawanna say they are not backing down regardless of the outcome of the Attorney General’s investigation. “It’s a love for our area. The reason we’re all here is because we love it, and we’re trying to protect it. Our motivation is protecting our community,” said Dempsey. Until the wrongful discharge of leachate is corrected, the expansion is stopped, and the community feels heard by DEP, the Friends of Lackawanna say they will do whatever it takes to keep their community safe.

Jake Conley contributed to this report

*DEP inspection data for Keystone shows 224 complaints were issued by the community about the landfill. The data shows a record of 716 inspections at Keystone since 1987. Of these inspections, the majority were either routine inspections or prompted by community complaints. Only 22 of the total 719 inspections noted in landfill violations, and not a single one of 224 community complaints against the landfill prompted a violation. Since 1987, only 3.2% of DEP landfill inspections found any violations of code or conduct.

**Based on data provided by the PA DEP, Public Herald’s August 2019 report uncovered 13 landfills in PA that receive radioactive fracking waste. In a report published August 5, 2020, Public Herald identified 17 additional landfills accepting oil and gas waste, bringing the total known number to 30 facilities. Keystone is one of the 17 sites that went undisclosed by the PA DEP.

*** In 1987, the Scranton Sewer Authority agreed to accept leachate from Keystone for treatment once a pretreatment facility at Keystone had been completed. According to a 1991 Gannett Fleming report to determine a feasible leachate line between Keystone and the Sewer Authority, when the community found out that leachate was going to be pumped through their neighborhood on it’s way to the sewer authority, they expressed serious concerns. After the community’s largely negative response, the City began to question the validity of the 1987 agreement due to health concerns. Ultimately, they withdrew from the agreement. Keystone sued the City for enforcement.

In 1990, a settlement agreement reached between Keystone, the City, and the Scranton Sewer Authority led to the construction of a separate, dedicated transport line to carry leachate from the landfill to the sewage treatment. According to this settlement, only the new dedicated line would be used for leachate and not the old gravity line leading to Outfall 2, as the community had demanded back in 1987. If Keystone intended to ever use the gravity line for leachate, they were to have it secured by permit, which at the time of the 2015 foul smell and local evacuations problems had not been done. The gravity line is still currently in use.

****Two months after the incident at Outfall 2 in December 2015, an EPA investigation was released officially stating that the landfill did not have a permit to send leachate down the unsecured gravity line to Outfall 2 and into the Lackawanna River. The Scranton Sewer Authority responded to this claim by quickly changing the permitting around the gravity line in question, ultimately claiming that the line had in fact always been safe for use.