Yellowstone Series: Government Uses Poison Linked to Parkinson’s in Montana Waterways Since 1948

Yellowstone Series: Government Uses Poison Linked to Parkinson’s in Montana Waterways Since 1948

BY EMMA LICHTWARDT AND JOSHUA BOAZ PRIBANIC FOR PUBLIC HERALD

November 29, 2022

Yellowstone Series: Part 1, a Public Herald investigative news project

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

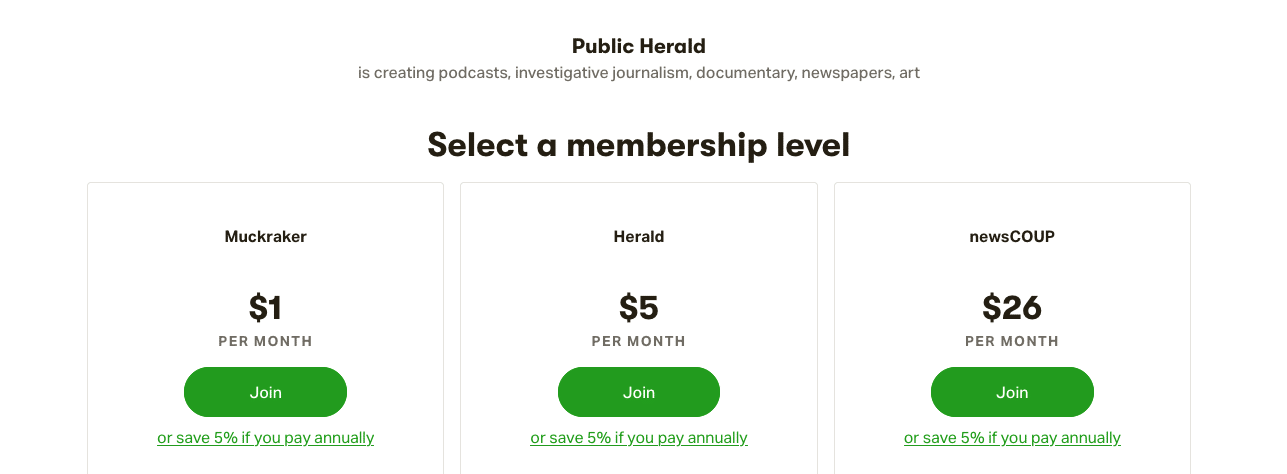

SUBSCRIBE

“I don’t give a shit who approved it. It’s killing my cattle.” John Dutton, Yellowstone, Season 5, Episode 2

Yellowstone, a Montana-based neo-western television series created in the summer of 2018, has become the most watched show in America, amassing over 12.4 million viewers on the opening of its fifth season this November 2022.

Set in the cities of Bozeman and Helena and in the mountain ranges of the Yellowstone National Park, creators Taylor Sheridan and John Linson built Yellowstone’s theme around a fictional Montana rancher named John Dutton. Played by award-winning actor Kevin Costner, Dutton faces off against two western worlds: the old vs. the new Montana. For five seasons, audiences have flocked to watch the Yellowstone Dutton Ranch cowboys fight off developers, capitalism, Native Americans, environmental activists, Californians, wealthy fly fishermen, and woke culture from destroying the ranchers’ western way of life.

In Episode 2 of Season 5, that fight took an unlikely turn toward pollution. In a flashback, cowboy Rip Wheeler recalls riding up a creek on the Yellowstone Dutton Ranch, where he and a young Dutton find dead fish and livestock after government-approved contractors had sprayed paraquat. “That’s my ranch down there — whatever you’re spraying it with, it’s in the creek now and it’s killing my cattle,” Dutton tells the contractors. “It’s killing everything.”

Sadly, the poisoned creek depicted in Yellowstone isn’t entirely fiction.

In the real world, paraquat is one of the most widely used weed killing chemicals on the planet, rivaling even glyphosate — the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup. Paraquat has been manufactured and marketed since the mid-1960s by Syngenta AG. Now the Chinese-owned producer has come under fire for undisclosed health risks linked to the chemical. The active ingredient in paraquat has been shown to pose a myriad of potential health risks and at the top of the list is Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s is considered one of the fastest growing neurological disorders in the world and the possible ties to paraquat have been gaining traction for years.

Public Herald has found that since 1948, in the name of conservation, the Montana government has been using another poison linked to Parkinson’s disease in lakes, ponds, and rivers across the state.

caption: Alex Poole setting up a Rotenone drip station in a tributary of Soda Butte Creek. © Yellowstone National Park, Neal Herbert

Government Dumps Pesticide Rotenone in Montana Waterways

In August of 2022, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) administered the fourth round of a fish-killing chemical poison, rotenone, to the North Fork of Spanish Creek, a tributary to the Gallatin River watershed outside of Bozeman, Montana.

First registered in the U.S. in 1947, rotenone has been grouped together with other pesticides, including paraquat, into a category of chemicals that are known to increase the risks of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s develops once a misfolded protein, called alpha-synuclein, builds up in the brain, kills nerve tissue and leaves behind waste brain matter known as a Lewy body. Recent evidence suggests Parkinson’s begins in the gut, triggering a degenerative gut-brain reaction through the vagus nerve.

Since 2019, FWP has been applying rotenone using backpack sprayers and drip stations to the North Fork of Spanish Creek in an attempt to restore native Westslope Cutthroat Trout (WCT) populations. The overall goal of FWP is to establish genetically distinct cutthroat to 20 percent of their historical origin in the upper Missouri river basin (WCT currently exists in less than 3 percent of their historic range).

As the North Fork of Spanish Creek gurgles through a remote landscape on the way to the Gallatin River outside of Bozeman, it passes through media mogul Ted Turner’s Flying D Ranch, one of the largest private ranches in the state. Portions of this project have taken place on Turner’s land with help from Turner Biodiversity who organized partners and funds for the work:

“Establishment of a self-sustaining population of cutthroat trout large enough to withstand environmental and demographic stochasticity and likely to persist over the long-term (>100 years) with little or no human intervention.”

caption: Dan Greene, with his dog Roy, holding a cutthroat trout caught in southwest Montana. © Jeremy Clark

caption: Rotenone drip station in a tributary of Soda Butte Creek. © Yellowstone National Park, Neal Herbert

caption: The entrance to Ted Turner’s Flying D Ranch on the way to the North Fork of Spanish Creek. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

caption: Public Herald journalist Emma Lichtwardt stands next to a bridge on the North Fork of Spanish Creek downstream from FWP’s rotenone treatment. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

caption: A gate blocks access to a private road on the Ted Turner Flying D Ranch to the North Fork of Spanish Creek where FWP built a concrete barrier that prevents non-native fish from traveling upstream. The barrier cost $430,000. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

caption: Emma Lichtwardt stands next to the North Fork of Spanish Creek downstream from FWP’s rotenone treatment. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

When Public Herald learned Montana was using rotenone to restore WCT populations, our first thought was Parkinson’s. In a variety of credible scientific studies, low doses of rotenone has been routinely linked to Parkinson’s disease. Specifically, rotenone is used in lab settings to induce symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in rats (1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Public Herald first contacted Mike Duncan, a FWP Madison-Gallatin Fisheries Biologist, in October 2021, who stated that he was “not familiar” with the ample studies connecting rotenone and Parkinson’s disease, despite the agency’s continued use of the chemical. Duncan implied that because FWP conservation projects use such low amounts of rotenone, there shouldn’t be a problem with toxicity. Duncan maintains, “I haven’t seen anything that would lead you down that path to think that there’s any long-term effects for humans or any other wildlife.”

But that doesn’t mean long-term effects haven’t been well-documented. From a story published by the Sante Fe New Mexican, two hydrogeologists blamed rotenone for their diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease after they applied the chemical in “one of the biggest fish kill operations in U.S. history.” At ages 34 and 37, their diagnosis put them in a group of 2% or less who have developed the disease before the age of 60.

FWP’s own 2019 draft environmental assessment report on rotenone use states, “Concern over a potential link between rotenone and Parkinson’s disease often emerges in piscicide projects…it is difficult to evaluate the potential risk to humans of developing Parkinson’s disease from aquatic applications of rotenone products.” However, the report’s findings don’t appear to have been communicated with FWP fisheries biologist Mike Duncan or included in public notifications of its use.

Public Herald has contacted several biologists, toxicologists, and ichthyologists outside of FWP; however, no one has been able to comment on the long or short-term toxicity or use of rotenone. In October 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) told Public Herald that they do not track rotenone usage on a national level and that permitting for the chemical is managed on the state level. National data is limited to nonexistent.

FWP records obtained by Public Herald show that since 1948 Montana agencies have applied rotenone 253 times at more than 200 different water bodies, to an estimated length of 533 miles of surface water throughout the state.

caption: Montana’s Fish, Wildlife & Parks rotenone master list from 1948-2022, obtained by Public Herald for the Yellowstone Series.

caption: Silas Teasdale fishes the sunset on Montana’s North Fork Flathead River. The area is a drainage connected to lakes that were treated with rotenone according to records released by Fish, Wildlife & Parks to Public Herald. © Aaron Teasdale for Public Herald

In an email correspondence with FWP, it was confirmed that the majority of Montana’s rotenone projects are conservation related; in other words, projects where non-native fish are killed off (as well as some aquatic invertebrates) and the subject area is repopulated with native species. A much smaller portion of projects involving the use of rotenone is dedicated to the removal of invasive species or illegal introductions, or are intended to benefit native or non-native sport fisheries.

However, the state has a shaky history with rotenone usage for conservation purposes such as in 2010 when Cherry Creek was accidentally poisoned with rotenone four miles below the conservation treatment area and the FWP had no idea how it happened.

Though requested, FWP hasn’t been able to provide Public Herald with results from the program that verify the effectiveness of rotenone use to restore cutthroat trout and eliminate non-native competitors. Even with evidence of the program’s success, however, questions would remain. How long does it work? What is the cost to the overall environment? How much does it cost to maintain efficacy?

Origins of Rotenone & its Effects on Wildlife

Rotenone is derived from the roots of several tropical members of the legume and bean family Fabaceae. Categorized as an isoflavone, rotenone blocks the cellular uptake of oxygen and is very effective at killing gilled animals. If ingested or long exposure times occur, rotenone can be deadly to gilled and non-gilled animals alike.

A study from 2014 found that “following oral ingestion, clinical signs of rotenone toxicosis may include pharyngitis, nausea, vomiting, gastric pain, clonic convulsions, muscle tremors, lethargy, incontinence, and respiratory stimulation, followed by depression. Respiratory depression and seizures lead to hypoxemia and hypercapnia… Exposure to rotenone dust via inhalation can cause pulmonary irritation and asphyxia. In rats and dogs, experimental inhalation of rotenone dust produced onset of signs earlier than following oral ingestion.”

But FWP and other conservation efforts around the country use terms like “naturally-derived,” “organic,” and “plant based” when describing rotenone, creating an illusion of safety and non-toxicity to the public.

The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation has found rotenone to be particularly harmful to native bee populations, stating that “organic does not mean benign.”

For the wildlife in Montana, when it comes to the effects rotenone, Mike Duncan says:

“It’s perfectly fine for a bear to come down and eat a bunch of those [rotenone-treated] fish or even drink the water. We post it throughout the treatment area at nearby trailheads, and in a couple of public releases, that we recommend not drinking the water either for livestock, pets, or human consumption. But honestly it would take a large amount [of water] at the concentrations we treat at to hurt a human… I wouldn’t personally drink water out of that stream, but it’s not going to kill someone.”

caption: Potassium permanganate colors the water below the station neutralizing rotenone treatment in Soda Butte Creek. © Yellowstone National Park, Neal Herbert

Is FWP using an amount of rotenone that would kill a human who drinks treated water? Probably not, Duncan is right about that. But the risks are not black and white. A disease like Parkinson’s has chronic effects that sometimes don’t manifest until many years later. If a chemical being used by the state, in public waterways, has even a small potential to cause chronic disease, or poses any threat to health, state agencies and the public should be well-informed of the risks.

With regards to wildlife, no precautions have been taken by FWP to prevent eagles or other predators from eating the dead fish after they’ve been poisoned by rotenone. FWP told Public Herald in October 2021, that rotenone-treated fish are not collected after treatments and are left to float to the surface, lining stream banks and lake edges until they eventually decompose – prime picking for the ample fish-eating wildlife in the surrounding areas.

For the fate of dead fish, FWP’s environmental assessment report states:

“Terrestrial scavengers contribute to the disappearance of carcasses, and piscicide-killed fish do not present health risks to organisms consuming them. Previous treatments have shown that fish killed by rotenone rapidly decay and are difficult to find even after a few days post treatment.”

FWP’s conclusions about rotenone’s impact to wildlife post-treatment often rely on testing model studies that were performed in the 1980s:

“Rotenone has a half-life of 14 hours at 24 °C, and 84 hours at 0 °C (Gilderhus et al. 1986, 1988), meaning that half of the rotenone is deactivated and is no longer toxic in that time.”

Though according to Microbac laboratories, rotenone degradation is not as simple as FWP reports. Depending on a variety of conditions — i.e. sunlight, temperature and sediment – rotenone could decay rapidly (within 24 hours) or take months.

“Because of all of these factors, [bold added] aquatic systems treated with rotenone cannot be labeled as nontoxic until the systems have been analyzed for rotenone and its degradation products, as well as other chemicals found in various rotenone formulations. The analytical methods used to determine the levels of rotenone (and other chemicals) must be sensitive enough to detect these compounds in the low ppb levels and specific enough to ensure identification of each compound.”

A 2015 study out of New Zealand that used “gamma distribution to determine half-life of rotenone, applied in freshwater” had a similar concern. This study looked at whether a more sensitive model for testing would change the dissipation results of rotenone in a treated waterbody. It found that when using this model, the half-life range of rotenone was ten times longer (or, roughly 50 days) in comparison to the usual method to determine its half-life.

What if federal and state governments used more sensitive models for testing rotenone post-treatment? What would the results be?

In the food chain, studies on rotenone following application are limited.

A report for Washington state notes that up to 0.696 parts per million (ppm) of rotenone was detected in dead fish residue — referencing the 1986 study from Philip A. Gilderhus that Montana uses for its own assessments — and that these concentrations were low enough to be insignificant to wildlife feeding on the carcass.

For humans, EPA established an acute dietary risk of rotenone toxicity at 0.01117 mg/kg/day (milligrams, per kilograms, per day) in 2007, but has yet to establish an acute dietary risk for terrestrial wildlife. In a 2002 independent study on rats, an injection of low-dose rotenone at 1.5 mg/kg per day over two months was enough to produce Parkinson symptoms.

Following studies linking rotenone to Parkinson’s in 2004, EPA required a human health “sub-chronic (28-day) inhalation neurotoxicity study” since it was registered as a residential and agricultural use product. In response, industry withdrew its registration of rotenone for all uses except piscicide, negating EPA’s need to perform a human health study.

As of 2022, EPA’s Health Effects Division (HED) attempted to minimize the growing body of independent studies identifying rotenone’s relationship to Parkinson’s, publicly stating “there was insufficient epidemiological evidence to conclude that there is a clear associative or causal relationship between rotenone exposure and Parkinson’s Disease.” HED’s evaluation was based on eight cherry-picked studies — excluding the majority of the work.

Overall, the chronic effects of rotenone toxicity in the food supply are not well understood. EPA reports generally cite its ability to either breakdown quickly, or metabolize into non-toxic excretable substances.

But federal and state explanations of toxicity for rotenone isn’t enough for biology professor Dr. John Stolz, director of the Center for Environmental Research and Education at Duquesne University, who’s studied the impact of chemicals in the food supply.

“The bottom line is they don’t want to pay people to capture the fish,” says Dr. Stolz. “They just want to throw in chemicals to kill everything. It’s the same thing as atrazine, in a sense that they don’t want to hire workers to pick weeds — so spray atrazine instead. But then you find out atrazine is a hormone that causes problems. Or in the case of glyphosate, that it’s now being detected in children’s cheerios.”

Dr. Stolz believes that the indiscriminate use of a toxic chemical has ramifications for the food web, and that safer methods should be applied.

Public Comment on Rotenone Treatments

To discharge rotenone, FWP must obtain an EPA permit, which opens the process up to public comment. That permit is part of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, or NPDES program under the Clean Water Act* which aimed to eliminate “the discharge of pollution into navigable waters…by 1985.” Unfortunately, instead of ending pollution of waterways, the NPDES permitting system actually prolongs it.

In Montana, EPA delegates its NPDES permit authority to Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). For now, both agencies handle enforcement and funding of the program. If DEQ fell short on their duties to oversee NPDES permits, EPA could end DEQ’s control.

For this story, Public Herald requested DEQ’s violation records for NPDES permits using rotenone. However, DEQ has not responded to the request. EPA told Public Herald, DEQ is currently undergoing “management changes” and they have no contact at this time for the NPDES program.

Under Montana law, FWP is required (§87-1-201(9)(a) Montana Code Annotated [MCA]) “to implement programs that manage sensitive fish species in a manner that assists in the maintenance or recovery of those species, and that prevents the need to list the species under § 87-5-107 MCA or the federal Endangered Species Act. Section 87-1-201(9)(a), M.C.A.”

Despite this law, the Montana rotenone projects are unsettling to residents of the state who find the use of chemicals in such conservation projects to be unnecessarily harmful to river ecosystems as well as the existing fish populations, be they native or non-native.

Dan Greene, a local fly fisherman who’s fished the Madison River for 17 years and lives near Quake Lake, told Public Herald, “Playing God with the water is like high-holing Mother Nature.” The term “high-holing” refers to someone stealing another person’s fishing spot, a reprehensible act in the fly fishing community.

caption: Dan Greene holds a shotgun next to a bus that he converted into a home in the Madison River valley. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

Public comment periods are used by the state to inform and seek opinion from state residents about projects carried out on public land. In the case of the Spanish Creek rotenone project, the comment period lasted from May 19 to June 3, 2021. Within those 15 days Montanans were expected to not only learn about and comment on the Spanish Creek rotenone project, but 21 additional fish removal projects proposed for the state.

News coverage for the 22 rotenone projects was weak at best, with not a single outlet citing the chemical’s link to Parkinson’s; information distributed to the public simply repeated “organic” talking points provided by the state’s press release. Overall, only 209 comments were received. 172 were in favor of rotenone use.

Photographs in this report depicting rotenone sprayers and drip stations were sourced from the Soda Butte Creek cutthroat restoration project in Yellowstone National Park (YNP), which operates independently from FWP and is pursuing efforts to restore the Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout (genetically different than WCT).

For the Soda Butte Creek project, 56 public comments were collected by the National Park Service in 2015. Twenty-nine comments were opposed to the proposed action, 20 supported it, 4 were in favor of non-native removal (but not with use of piscicide) and 3 were unable to discern support or opposition (or were a duplicate entry). No comments on file addressed concerns over Parkinson’s disease.

caption: Soda Butte Creek Drainage with a hot spring terrace in the foreground and an open valley with mountains surrounding it in the background. © Yellowstone National Park, Neal Herbert

Alternatives to Rotenone

Public Herald spoke with Michael Garrity, the executive director of Alliance for the Wild Rockies, about rotenone treatments in the name of conservation. One of the few people who has written against rotenone in Montana, Garrity asserted that chemical conservation is not really conservation at all if it renders delicate ecosystems sterile and/or disrupted for prolonged periods of time. “The attitude in the US is that poisons are safe for humans until proven unsafe,” Garrity says, “and I just don’t think that’s an acceptable risk,” especially given the potentially viable alternatives such as electrofishing.

Electrofishing temporarily shocks fish in a section of water using an electrical current. The fish float to the surface and can be counted for assessment and returned to the river, or permanently removed.

In July 2021, Garrity wrote a piece in the Daily Montanan detailing the lengths a Wyoming town went through to halt a rotenone project in a local stream. Allegedly a successful endeavor, the conservation effort was attempted using what was considered safe alternatives to rotenone: electrofishing and increased catch limits of non-native species. In this piece, Garrity raises a valid question: If Wyoming can do better, why can’t Montana?

Public Herald’s findings in this report were sent for comment to Montana U.S. Senator Steve Daines, Governor Greg Gianforte, Yellowstone National Park Service (YNP), as well as Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP). Senator Daines and Governor Gianforte have not responded, while YNP stated that they have no comment at this time.

FWP has informed us it would take up to 20 days to process a response.

Coming in 2023 for Public Herald’s Yellowstone Series:

- Government’s Rotenone Process & Science

- Wealthy Ranchers Finance Poison in Montana Waters

- Fly Fishing Montana

- Alternatives for Montana

- Mapping a History of Water Pollution

- Montana: Old vs. New