Under “Chief’s Orders” Ohio Operates a Radioactive Industry Off The Record

Under “Chief’s Orders” Ohio Operates a Radioactive Industry Off The Record

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

SUPPORT newsCOUP

Public Herald is a nonprofit newsroom that holds those in power accountable. You can receive our latest breaking stories by subscribing to our newsletter or becoming a Public Herald Patron.

by Talia Wiener for Public Herald, From Editors Joshua Boaz Pribanic and Melissa A. Troutman

July 30, 2021 | Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers, TENORM Mountains

Part 1 of Ohio TENORM Mountains 3-part series. Read Part 2. Get the story in print through one of seven Ohio Ogden papers, starting front-page at Sandusky Register. Contributions to this series were made by Sandusky Register Editor Matt Westerhold and Journalist Tom Jackson.

Everyone knows that oil and gas wells produce oil and natural gas. But few people understand that these wells also produce radioactive material that is being disposed of in communities alongside household trash and making its way into rivers used for drinking water and recreation.

The oil and gas industry consistently claims that the levels of radioactivity in its waste and byproducts are safe – but a growing body of data proves otherwise.

caption: A flowback containment pond holding TENORM waste from a Marcellus Shale natural gas drilling operation on State Game Lands 59 in Potter County, PA. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines the radioactive portion of this waste as TENORM (technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material), and in communities across shale plays like Ohio, TENORM is piling up in watersheds.

While Ohio has strict regulations governing radioactive waste that come across its borders — the O.R.C. 3734.02 — the rules are not actually enforced. The state code doesn’t require the kind of extensive testing necessary to adequately measure radioactivity in TENORM waste.

Next door in Pennsylvania, which exports massive volumes of oil and gas waste to Ohio, the same shale basins — i.e., the Marcellus and Utica Shales — are also being exploited. But unlike Ohio, Pennsylvania is at least gathering some data. In 2016, the commonwealth released a TENORM study on fracking’s oil and gas waste that has begun to shed light on the dangerous game being played with radioactive material in Ohio.

In fact, one attorney interviewed for this series stated – “The state is acting illegally.”

After 15 months of reporting and research, this three-part series on radioactive material from the oil and gas industry is Public Herald’s latest state-wide investigation of regulatory failure in and around the fracking industry, this time focusing on Ohio: Welcome to Part One.

Never before in the history of America has the nation undertaken an experiment with radioactive material like the one happening now across the country thanks to technological advances in hydraulic fracturing, a deep, water-intensive, chemical-laden process to extract hard-to-reach fossil fuels.

The formations being “fracked” in Appalachia, including the state of Ohio, from the Marcellus and Utica Shales, happen to be the hottest in the country — as in the most radioactive. In 2020, Harvard scientists revealed that radiation downwind of unconventional fracking development is significantly higher than background levels and more so in the Marcellus and Utica Shale due to the higher uranium content of those formations. According to the industry itself, every part of the oil and gas industry involves radioactivity. A 1982 report commissioned by American Petroleum Institute stated: “[a]lmost all materials of interest and use to the petroleum industry contain measurable quantities of radionuclides that reside finally in processing equipment, product streams, or waste.”

The safe management of the industry’s radioactive waste is paramount to protecting public health, worker safety, and the environment. So how is it going in Ohio?

Here’s the gist — oil and gas companies drill down deep into the earth and blast water and chemicals into bedrock to access minerals. The process produces waste that includes drill cuttings, synthetic drilling muds, fracking chemicals, and naturally occurring radioactive material (NORM) that would otherwise stay locked underground.

That waste is taken to facilities across the country, and in Ohio that includes local landfills, where rain filters through trash, carrying contaminants with it.

This is where much of the story has been lost, until now.

caption: Frac tanks at Republic Services Carbon Limestone Sanitary Landfill at 8100 South Stateline Road in Lowellville, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

In landfills, the contaminated rainwater called “leachate” is transported to local sewage treatment facilities, which add the polluted liquid to sewage for processing before dumping the leftovers into local waterways. But sewage is not treated for radioactive materials, so whatever TENORM goes into the facility also goes into the river, eventually. Or, in some cases this can be even worse, TENORM can be lodged in sludge and filters making them radioactive for any material they come into contact with.

But Ohio’s TENORM problems go beyond landfills and sewage waste treatment plants, which are governed under established state rules; there is another set of facilities authorized to handle fracking’s radioactive material, called “Chief’s Orders” facilities. Under Chief’s Orders, privately-owned facilities have special permission to operate outside of existing law. And it all happens off the record.

caption: 4K Industrial Water Recycle Plant, a Chief’s Order facility in Martins Ferry, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

How did radioactive waste get a special permit that left it off the record?

In Ohio, the guessing game being played with the radioactive material from fracking is all happening in plain view of the Ohio EPA (OHEPA), the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), and the Ohio Department of Health (ODH) — the three regulatory bodies responsible for keeping everyone safe from industrial pollution.

When a private company wants to “store, recycle, treat, process, and dispose of brine and other waste substances,” it needs one of the Chief’s Orders from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), according to Title 15 of the Ohio Revised Code.

Last amended in 2013, the Ohio Revised Code was meant to call for the adoption of rules regarding the proper care of oil and gas waste under Chief’s Orders. But as of 2021 those rules have not been finalized.

Eight years later, Chief’s Orders facilities, who would handle radioactive waste from fracking, are operating with no updated rules or oversight. Today, that leaves the potential for unregulated radioactive waste to enter rivers and watersheds across Ohio.

caption: Tanks from the Duck Creek Chief’s Order Facility hidden behind a fence and private lot in Summit County, Ohio. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

Teresa Mills, executive director of the Buckeye Environmental Network, told Public Herald that before the Chief’s Orders system was implemented in 2014, Ohio had nothing on the books to regulate the private fracking waste industry. Eight years after the implementation of the Chief’s Orders system, there’s still nothing.

The state does not currently offer an online database of Chief’s Orders facilities, but Public Herald has identified 13 facilities actively storing or disposing of “brine, crude oil, natural gas, or other fluids” under Chief’s Orders, there are 35 facilities that are no longer active, and an additional 19 active facilities that have Chief’s Orders for operations other than storage or disposal: including brine and drilling mud recycling, truck washing, and waste solidification. Six other facilities received similar Chief’s Orders and are no longer active.

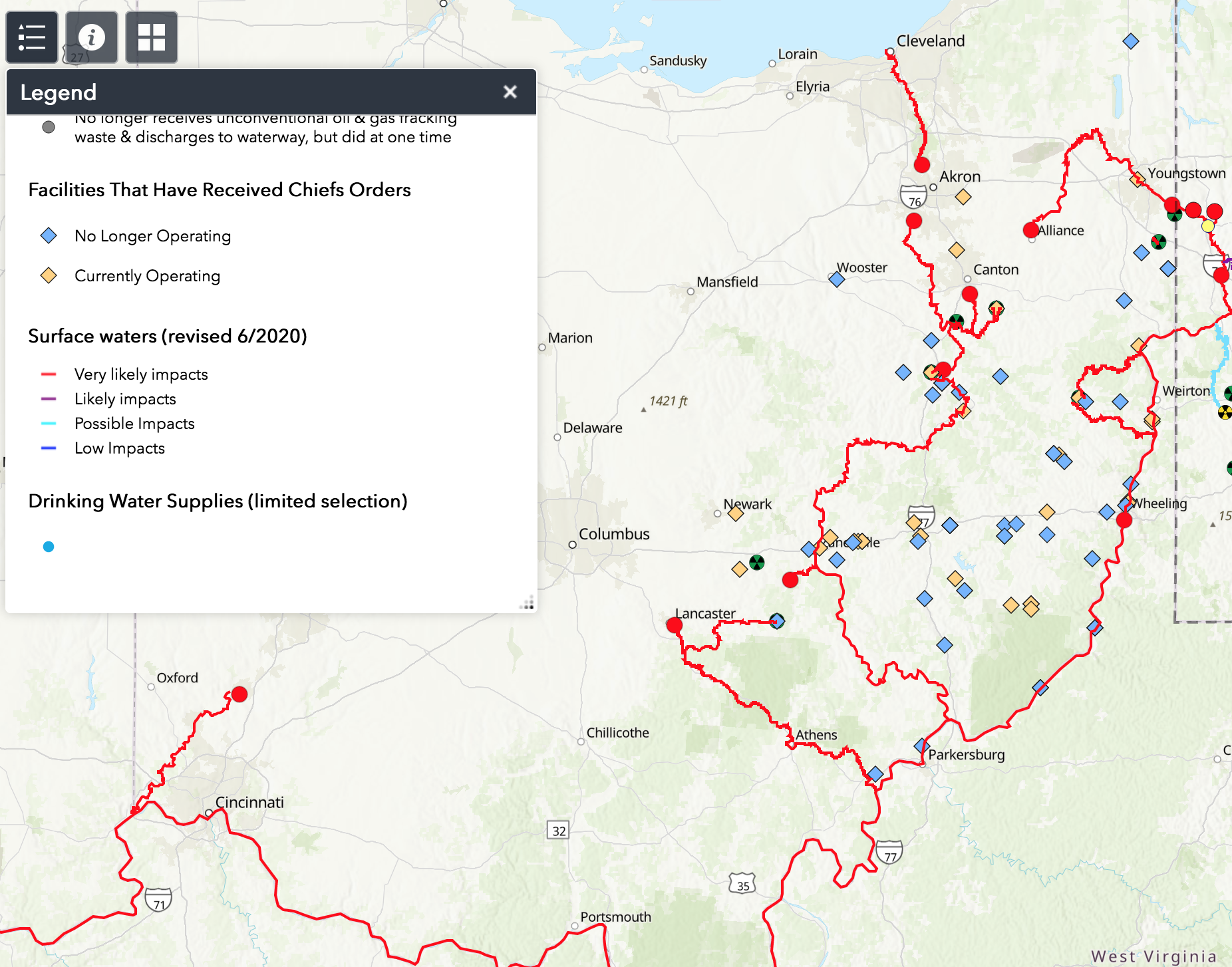

caption: Public Herald’s Ohio TENORM map showing Chief’s Orders facilities that are operating or no longer operating (yellow and blue diamonds). The map also includes the location of eight landfills accepting radioactive fracking waste (trefoil symbols), the POTWs who are treating their radioactive leachate (red dots), and the 26 waterways impacted by the POTW NPDES permits (red lines). © Novare Collective for Public Herald » Click for interactive map »

Without detailed reporting requirements for the Chief’s Orders facilities, there’s no way Public Herald could find out how much waste has traveled through the 73 facilities who’ve handled fracking waste since the first Order was granted in 2014. That year, Food and Water Watch (FWW) and the FreshWater Accountability Project (FWAP) filed a complaint requesting a mandamus action against the state of Ohio and ODNR, pushing for the removal of 23 facility Orders active at the time and for no further Orders to be granted.

The complaint states: “All Chief’s Orders issued by ODNR related to fracking waste facilities are illegal because they have not been issued as a result of procedures and requirements promulgated pursuant to O.R.C. § 1509.22.”

In 2018, the Supreme Court of Ohio denied an appeal of the action, affirming a lower court’s decision that FWW and FWAP lacked standing, concluding that the plaintiffs did not demonstrate that their individual members would have standing in their own right. To establish standing, the court stated that “a litigant must show that it has suffered an injury that is fairly traceable to the defendant’s allegedly unlawful conduct, and likely to be redressed by the requested relief.”

In other words, come back and see us after damage is done. The denial of FWW and FWAP’s appeal means that Chief’s Orders continue to be granted in Ohio without procedures or requirements attached to them.

In a July 2020 email, ODNR Public Information Officer Adam Schroeder told Public Herald that the Division is still in the process of “rewriting and reorganizing” all the rules in O.R.C. 1501 – O.R.C. 1509.

“No end date has been determined,” Schroeder said.

When asked by Public Herald about why it’s taken eight-plus years to set new rules for Chief’s Orders facilities, Gov. Mike DeWine’s office instead had ODNR provide a statement:

“All oil and gas waste facilities operating under a Chief’s Order have to comply with the terms and conditions set forth in the Chief’s Order and all oil and gas rules/law in the Ohio Revised Code 1509 … and the Ohio Administrative Code 1501:9 … The Division of Oil and Gas Resources Management (the Division) will continue to diligently regulate all of Ohio’s oil and gas waste facilities as the formal rulemaking process continues.

The Division develops draft rules by using the scientific expertise and experience of our staff – then by engaging stakeholders and welcoming public comments as outlined in the Rulemaking process. This open and inclusive process creates effective and reasonable regulations for all parties – Ohioans, the regulated industry, and the regulator.”

Meanwhile, the Ohio Environmental Council, one of the most powerful legal organizations working to keep Ohio clean from fracking, is not actively pursuing legal action regarding Chief’s Orders facilities, Communications Director Emily Bacha said in December 2020.

A Revolving Door & Health Issues Tied to Facilities Accepting TENORM Leachate

In Youngstown, Ohio, the largest city in Mahoning County, more than half of the children live in poverty. The city has the highest childhood poverty rate in the state at 57.5 percent, according to the 2018 5-Year American Community Survey. Surrounding Youngstown are four separate facilities processing radioactive fracking waste: two landfills (Carbon Limestone Landfill and Mahoning Landfill), one wastewater treatment plant (Lowellville WWTP), and one Chief’s Order facility called Ground Tech, Inc..

caption: Passersby at the fountain inside Fellows Riverside Gardens in Mill Creek Park in Youngstown, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Ohio resident Lynn Anderson has spent nearly a decade working with FrackFree Mahoning Valley to keep Poland Township — southeast of Youngstown in Mahoning County — and the surrounding area safe from radioactive contamination. But, the fight against the industry often seems unwinnable, Anderson said.

“They just feel that our lives are worth nothing, that we’re expendable,” said Anderson. “People’s lives matter. You can’t sacrifice them for corporate profit.”

caption: Lynn Anderson at Republic Services Carbon Limestone Sanitary Landfill at 8100 South Stateline Road in Lowellville, Ohio. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

But right now — by skirting regulations, breaking laws, and violating public trust — the health of industry workers, the public, and the environment appear to be sacrificed for profit in Ohio. As the next two parts of this series will continue to reveal, Ohio’s fracking waste disposal industry is broken, dangerous, and enabled at every level.

Investigative Journalists Joshua Boaz Pribanic, Melissa A. Troutman, Jake Conley and Elijah Labby contributed to this story

Funding for this series was made in part by the Park Foundation