“They’re a Bunch of Liars” – Records Expose Lies About Injection Well Safety

“They’re a Bunch of Liars” – Records Expose Lies About Injection Well Safety

BY MELISSA A. TROUTMAN AND JOSHUA BOAZ PRIBANIC FOR PUBLIC HERALD

October 27, 2022

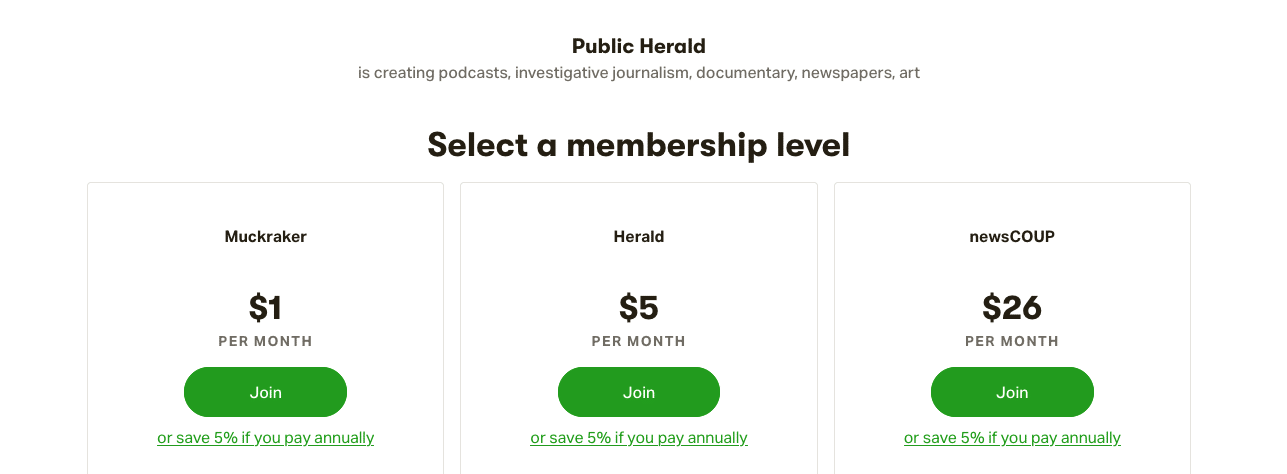

Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers, TENORM Mountains

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

Laurie Barr has been plagued by smelly and seeping toxic waste in her work to hunt down and plug abandoned oil and gas wells. Her home state of Pennsylvania is the second largest producer of natural gas in the United States and has more than 200,000 abandoned wells, more than anywhere in the country.

The waste created by the oil and gas industry, which is full of chemicals, heavy metals, and radioactive material, is a complex problem plaguing communities across the United States, especially those in shale basins like the Marcellus.

One of the most contested methods of oil and gas waste disposal is to inject it underground into older oil and gas wells. These converted “underground injection control” (UIC) wells, like abandoned wells, can be sources of toxic pollution and climate-disrupting methane.

Barr believes there are thousands of injection wells operating all across Pennsylvania, especially the Allegheny National Forest, with little to no oversight. Many of them are abandoned by oil and gas companies that closed their businesses without cleaning up and properly retiring their wells.

caption: An abandoned well located in a stream in Pike Township, Pennsylvania. The well, according to Laurie Barr, is not recorded in the DEP database. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

The story that the oil and gas industry and government officials tell the public is that injection wells are safe and pose no risks to fresh water.

In a presentation to residents of Bear Lake, where several injection wells have been used for oil and gas waste disposal since 2012, industry claims the waste is “not toxic.”

Contrary to that claim, researchers have consistently found that contaminants in oil and gas waste are toxic to aquatic life, land and plants, and water. Yale University, among others, has also found oil and gas waste toxic to humans.

In its fact sheet about injection wells, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) writes: “The history of underground disposal shows that it is a practical, safe and effective method for disposing of fluids from oil and gas production.”

Barr disagrees.

“They’re a bunch of liars,” she said.

According to Pennsylvania’s public records, she isn’t wrong.

caption: Laurie Barr beside an abandoned well located in a stream in Pike Township, Pennsylvania. The well, according to Barr, is not recorded in the DEP database. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

To see how injection wells are actually performing, one must go on a hunt through multiple DEP databases, compare datasets, request records via Right-to-Know law, then scrub and synthesize data to come up with an answer.

Public Herald began this daunting task in spring 2022, starting with a review of citizen complaints related to injection wells. And so far, Pennsylvania’s complaint records reveal that, like Barr said, the story industry and state are telling the public about injection well safety and reliability is a lie.

Hunting Injection Well Numbers

When researching injection wells, the first and most basic question you need to ask is – how many are there? It seems like a simple enough question.

But as it turns out, the number of injection wells in Pennsylvania changes depending on where you look.

There are two types of underground injection wells in Pennsylvania – Class IID injection wells for oil and gas waste disposal, and Class IIR injection wells for enhanced recovery, where fluids are injected underground to push up more oil and gas. All of them are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the Underground Injection Control (UIC) program.

It may seem like these are two separate kinds of wells, but both enhanced recovery “R” and disposal “D” wells inject waste underground where it remains in perpetuity. There are some differences, however. According to EPA, enhanced recovery wells only inject conventional oil and gas waste; disposal wells inject both conventional and unconventional waste. Also, enhanced recovery injection wells are not regulated as stringently as the Class IID disposal wells. EPA requires extra federal regulations for disposal wells to protect drinking water.

Since 1984, it’s been EPA’s responsibility to handle injection well permitting, and in some states, federal authority of injection wells is shared with state regulators. In Pennsylvania, authority is shared with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Once a company gets a permit from EPA, they also have to secure one from DEP.

Both agencies make the number of injection wells public. The trouble is, those numbers are hard to nail down. At first glance, they don’t even match.

EPA lists 29 companies permitted for 45 underground injection wells in Pennsylvania on its website. We had to email EPA for confirmation about whether these were all disposal wells. EPA told Public Herald that 18 are disposal wells operated by 12 companies, and the other 11 injection wells listed are for enhanced recovery. So, let’s say the number is 18 disposal wells by 12 companies.

The DEP, however, lists only 16 disposal wells for 10 companies on its Underground Injection Control (UIC) webpage. According to EPA, DEP’s number is lower because the department hasn’t issued permits for some wells that EPA has.

Then there’s DEP’s “waste disposal” well database which also includes injection wells. It lists 16 companies with 23 injection well permits dating back to 1961. Of these, 7 are Plugged. We won’t count those, even though they too can leak and pose pollution risks. Of the remaining 16 “waste disposal” wells, 14 are listed Active, 1 Regulatory Inactive, and 1 Revoked. These are the ones DEP lists on the aforementioned UIC webpage.

But these numbers are far – FAR – from all of Pennsylvania’s injection wells.

DEP Press Secretary Jamar Thrasher also sent Public Herald a third list of 10,543 “injection wells” that Thrasher said are “likely used for flooding the formation to push oil or gas to a production well” – a.k.a. enhanced recovery “R”.

“Likely”, but not certainly.

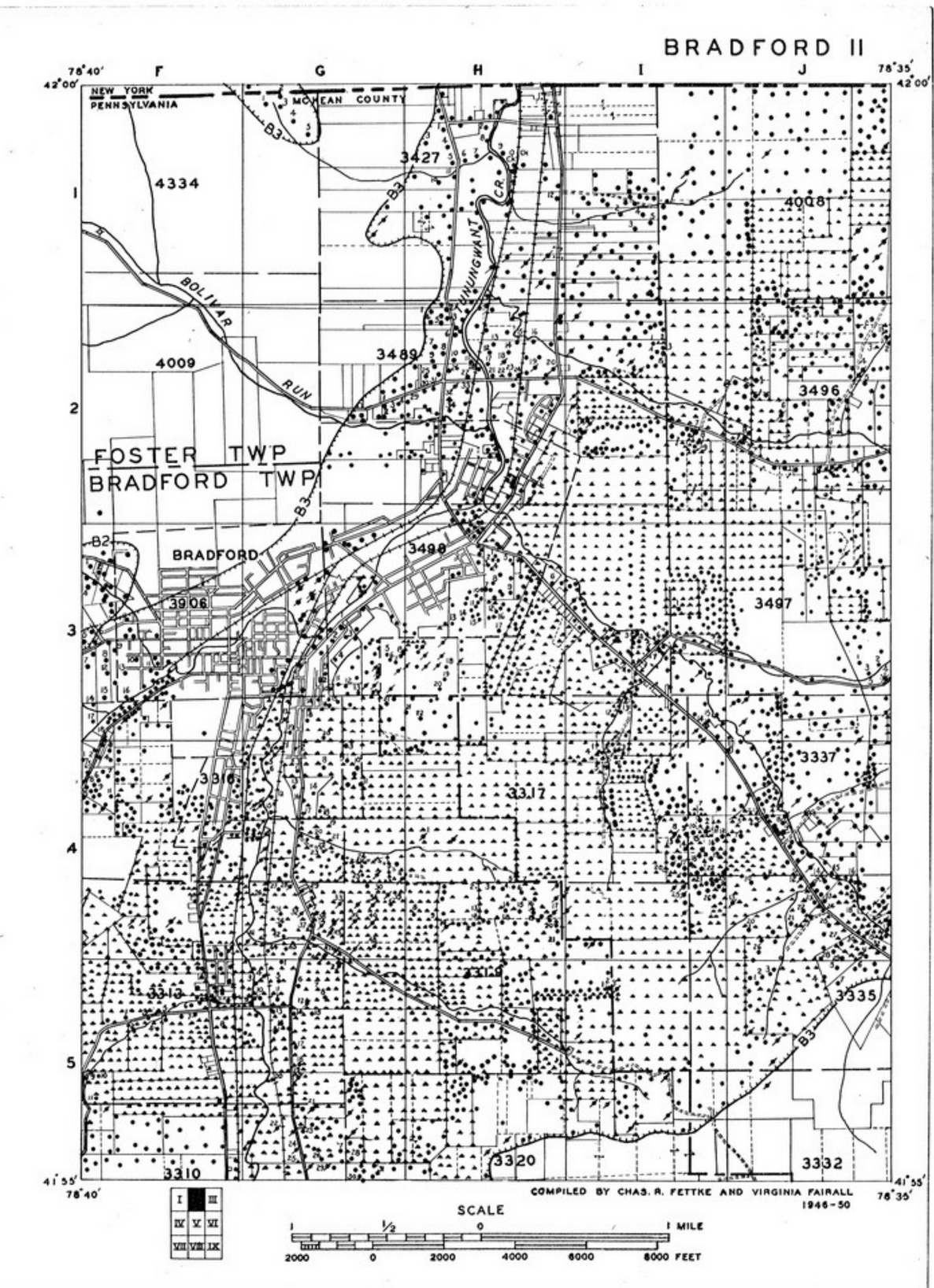

Barr isn’t surprised that there are that many. She shared maps of historic oil fields in northern Pennsylvania that show far more “flood” wells for injection than actual oil wells. There were so many, the landscape was almost completely covered in them.

caption: The 1951 Oil and Gas Atlas of the Bradford Quadrangle has several maps of oil, gas, and “water intake” wells. The water intake wells, shown as triangles, are what Barr believes are “flood wells” for fluid injection. Hundreds of wells pepper the approximately 6 square mile area, and more wells have been drilled since.

Public Records Refute Industry & State Claims of Injection Well Safety

In 2021, Public Herald was deposed for a lawsuit against Grant Township, a municipality in Indiana County where Pennsylvania General Energy (PGE) is trying to inject its oil and gas waste into a Class IID disposal well permitted by EPA and DEP.

Attorneys for Grant used Public Herald investigations as evidence of DEP failure “in its duty to protect Pennsylvanians’ clean air and water.”

With the DEP attorneys at its side, PGE’s attorney argued that injection wells are not a risk to water in Pennsylvania, pointing to the state’s own citizen complaint investigations released by Public Herald in 2017. PGE claimed there was only one single case among the complaint records where a resident reported a problem connected to injection wells, and that the complaint had nothing to do with water contamination.

Therefore, water contamination from injection wells, they argued, was a non-issue.

But either by ignorance or omission, the industry and state failed to acknowledge over a dozen additional complaints related to injection wells in those records, including ones that implicated the pollution of water sources.

During the deposition, Public Herald was unsure how many complaints dealt with injection wells, but after industry made a point of it, we decided to take a closer look.

A simple keyword search of the 2004 to 2016 complaint database immediately revealed that, contrary to PGE’s arguments, the citizen complaint records show at least 14 injection well complaints – not only one. And that’s just the surface of what’s out there.

In the records, there are an additional 781 complaints related to abandoned wells, which include “flood” or enhanced recovery injection wells. Abandoned wells can also be conduits for contamination by injection wells that introduce pressure and fluids nearby.

To dig further, Public Herald filed a Right-to-Know (RTK) request for injection well complaints from 2016 to 2021 and found even more related to water. In fact, an astonishing 83% of these new records described damage to water supplies and violations to Pennsylvania’s Clean Streams Law.

Residents’ Fears Become Reality

At least half a dozen communities in Pennsylvania have tried to stop injection wells in order to protect their water, asking regulators to consider documented cases of water pollution and earthquakes caused by injection wells. Among them are Clara Township in Potter County, Highland Township in Elk County, Brady Township in Clearfield County, Columbus Township in Warren County, Plum Borough in Allegheny County, and Grant Township in Indiana County.

Most of these communities got injection wells anyway, except Grant Township. Three years after issuing an injection well permit and suing the township for interfering with its authority, the DEP revoked the injection well permit. (The department didn’t drop its lawsuit, however – this is the case where Public Herald was deposed and our complaint reports were used as evidence.)

Lo and behold, years later, residents’ fears about water contamination in the communities that ended up with injection wells have become reality.

Despite industry and regulators pushing a story that injection wells meet strict safety standards, citizen complaints to the DEP offer a glimpse into how those standards fail to protect water.

Public Herald’s latest RTK of DEP’s citizen complaint records uncovered 18 complaints from 2016 to 2021 for underground injection control (UIC) wells, 15 of which included water pollution concerns (83% of complaints).

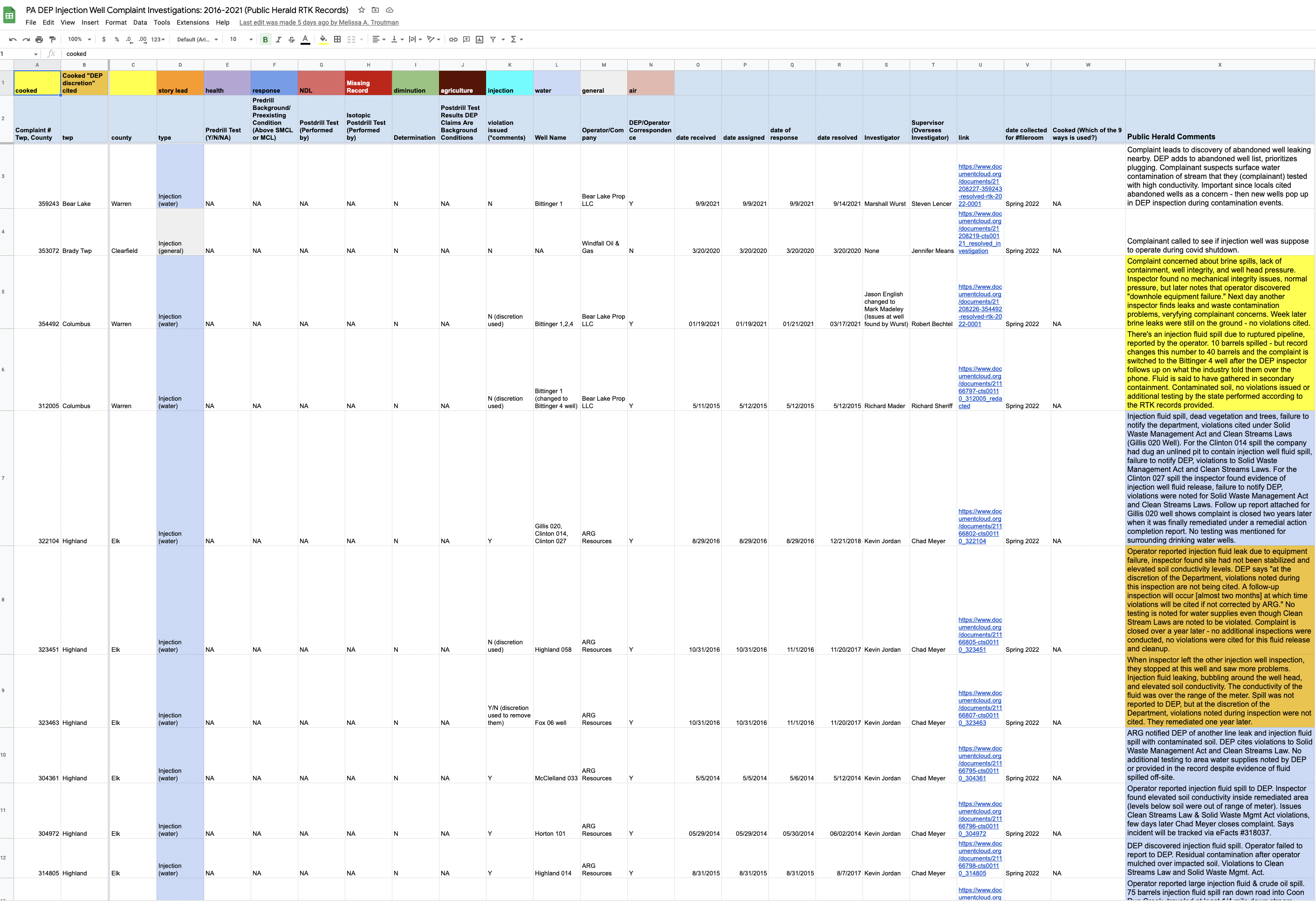

Chart: Public Herald’s spreadsheet on DEP’s injection well complaints. The spreadsheet records what the complaint documented and includes notes from Public Herald about each complaint.

Eight of the 18 injection well complaints resulted in violations to the commonwealth’s Clean Streams Law. But at five more injection wells, DEP inspectors found Clean Streams Law violations and chose not to issue citations, which makes the real total of complaints with Clean Streams Law violations 13 of 18 complaints.

Highland Township, Elk County amassed the most complaints – 11 out of 18 – all involving threats to water.

Highland Township tried to prohibit injection wells in 2013 in order to protect “local water quality and health” but were bullied into submitting under threat of litigation by Seneca Resources.

“Discretionary” Non-enforcement of Violations

In eight of the 11 Highland Township cases, dating 2014 to 2016, DEP issued Clean Streams Law violations to ARG Resources for leaks, spills, and contamination (#322505, #322126, #316156, #316151, #314805, #304972, #304361, #322104).

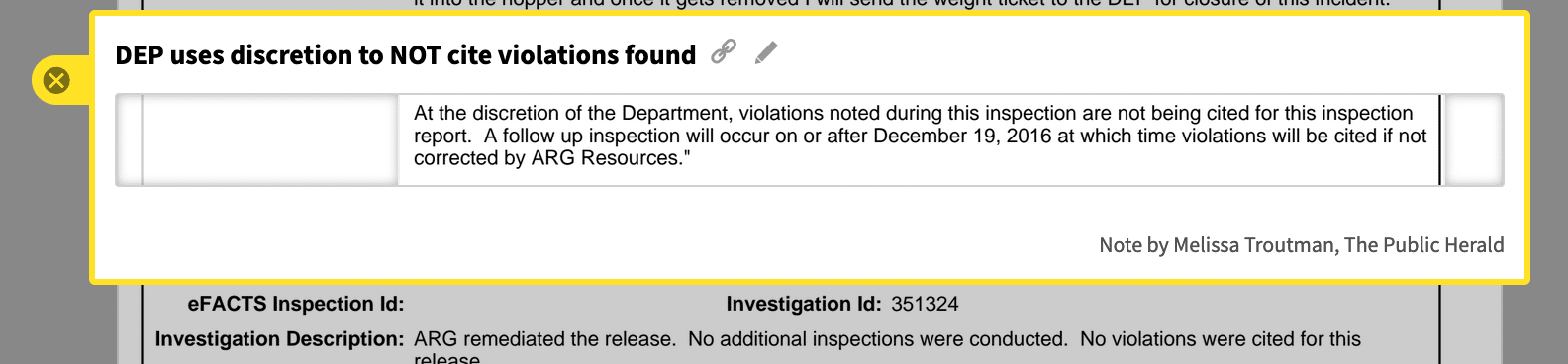

In the remaining three cases (#323451, #323463, #323454), DEP noted similar violations at ARG Resources sites but chose not to issue violations, citing “Department discretion” in two of them (#323451, #323463).

In cases where discretion is involved, DEP asks ARG Resources to fix the problems in lieu of levying citations. The company eventually complies, erasing the violations from the company’s compliance history.

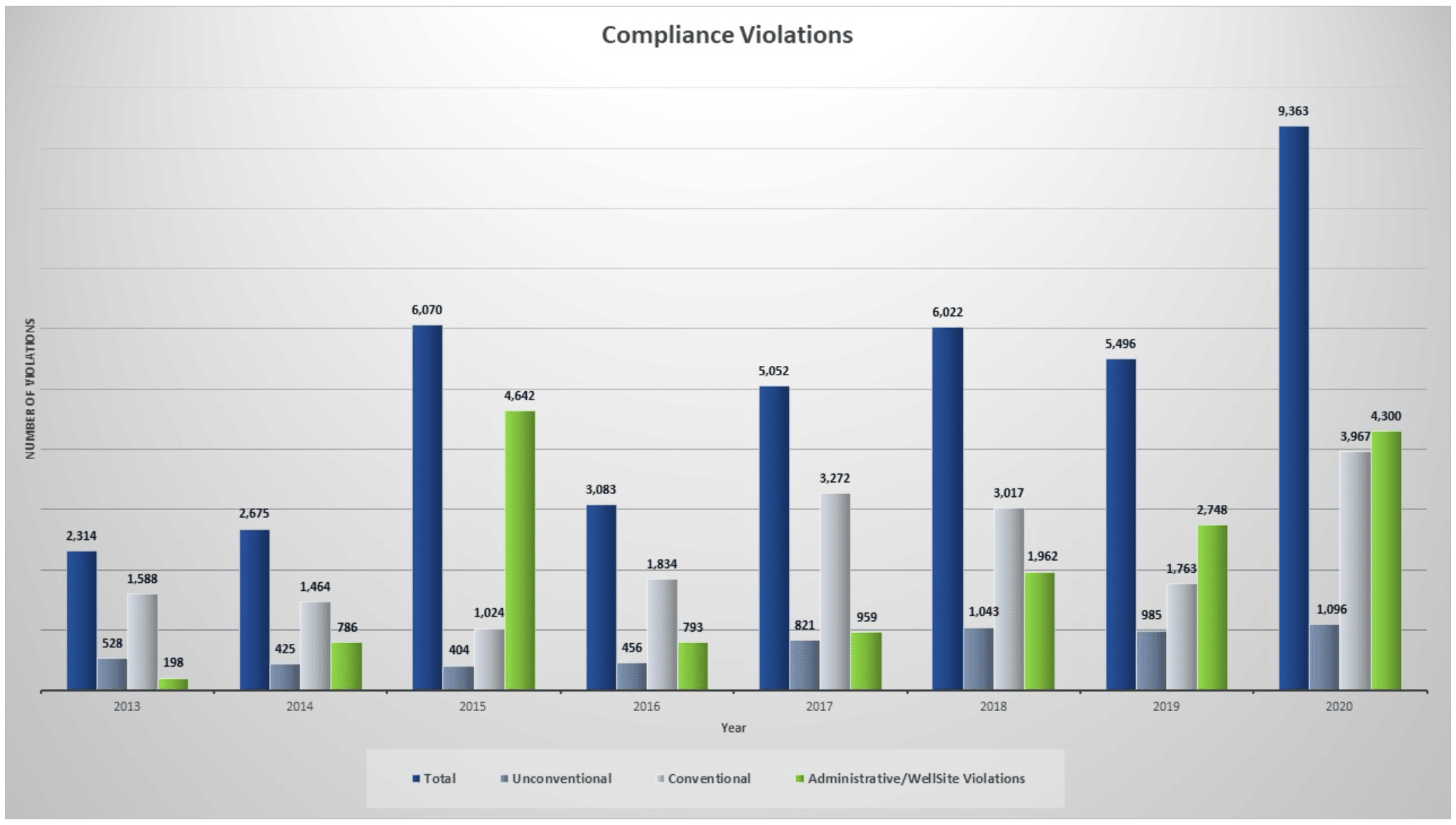

But this paints an inaccurate picture of industry conduct, masks real environmental impact, and skews violation statistics that DEP reports to the Governor’s office as well as the public.

caption: Graph of violations issued to oil and gas companies by DEP. Source: DEP 2020 Oil & Gas Annual Report

Three years later, ARG was “out of business” leaving DEP and EPA “to attempt to clean up the site” in Highland Township.

“The state turns a blind eye to anything in the oilfield that makes one company look bad,” Barr said. She has documented dozens of violations by “bad actors” who DEP has permitted to pollute without being held accountable.

In 2011, township officials in Columbus, Warren County tried to prohibit regulators from permitting the injection of oil and gas waste imported from outside the township, but their efforts failed.

caption: youtube video of news report about Bear Lakes injection well.

Almost 10 years later, the Bear Lakes Bittinger #2 injection well in Columbus (complaint #354492) leaked oil and gas waste and suffered a “downhole equipment failure” in 2021. But even though DEP cited other companies for similar violations, they chose not to issue Bear Lakes any violations for these infractions.

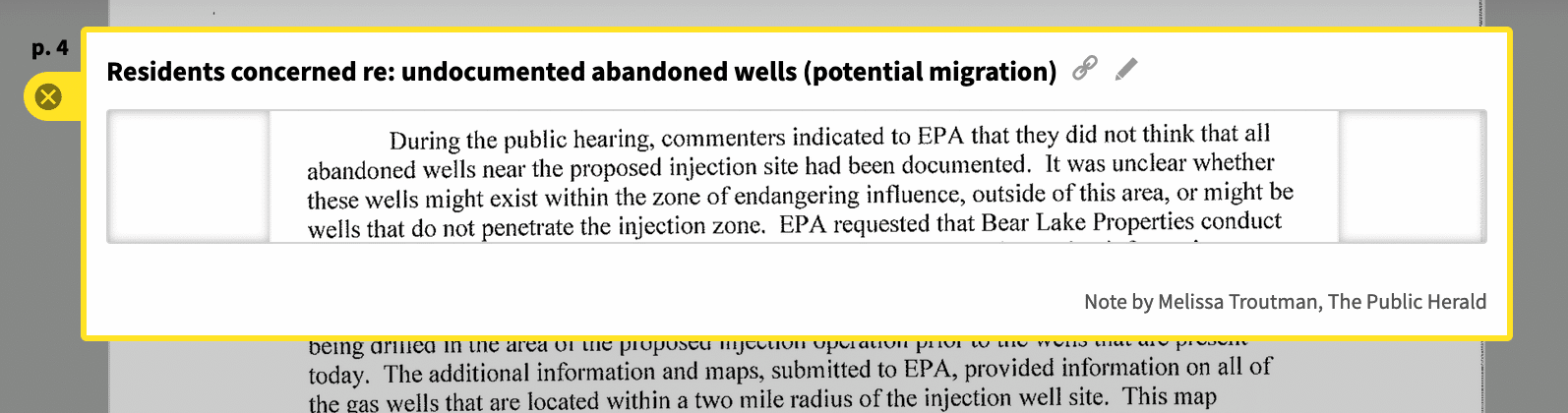

Also in 2011, Warren County citizens warned regulators about undocumented abandoned wells in the area that posed a threat to their water supplies if injection wells were approved. EPA and DEP issued injection well permits anyway.

In Bear Lake Borough, in 2021, complaint #359243 led to DEP’s discovery of a leaking abandoned well adjacent to the Bittinger #1 injection site.

Abandoned wells, like the tens of thousands that Laurie Barr hunts down to get plugged, can communicate with injection wells, providing a pathway for pollution to spread underground that can travel for miles.

Pittsburgh’s New Neighbor: Injection Wells

Just north of Pittsburgh, close to the city’s water supply, an injection well in nearby Plum Borough suffered mechanical issues in 2021 the same time that residents next door reported water problems.

Katie Sheehan lives less than 500 feet from Penneco Resources’ Sedat injection well. First permitted by DEP in 2020, Penneco started injecting waste shortly after.

In its review of the permit, DEP concluded “Penneco’s proposed operation is sufficient to protect surface water and water supplies.”

But in the summer of 2021, the spring at Sheehan’s parents’ home next door went bad for the first time ever. Sheehan filed two complaints ( #357914 and #359730) with DEP describing the spring’s foul odor and taste, as well as “strong acid-like odors…irritating to…eyes, skin, and nostrils” coming from a water well on her own property.

Sheehan told Public Herald that her family was told they shouldn’t drink the water. Penneco hauled drinking water for Sheehan’s parents and their cattle for a couple months until DEP concluded that the injection well wasn’t causing their water pollution.

“My dad has lived in that area his entire life, and there was never a problem with color, clarity or odors of the water. And there was a mechanical failure of the injection well, and around that time is when we noticed issues with my parents’ water.”

Later, the company offered to drill a new water well for Sheehan, but only if she signed an agreement that she would never talk about them to anyone, including media, or sue them over anything in the future. She declined.

Sheehan now rents a 2,500 gallon water tank, pays to get water trucked in, and buys bottled water for drinking. It costs her about $200 per month. She considered installing a cistern to collect rainwater, but air monitors on her property detect spikes in volatile organic compounds (VOCs) since the injection well started operating. Some days, Sheehan added, the air smells like chemicals, causing headaches.

“A cistern isn’t gonna rule out contaminants, because obviously if it goes up into the air it’s going to come back down in rainfall. Right now, the safest option I feel is to continue having the water trucked in,” she said.

Penneco hasn’t offered to pick up the tab.

“It’s a daily stress,” Sheehan said. “Everytime [trucks] go up you just think, well, there’s goes another load of carcinogenic material that they’re gonna dump.”

Oil and gas waste, including what’s being trucked past Sheehan’s home and dumped into injection wells, contains high levels of radium-226, a human carcinogen with a half-life of 1,600 years. It’s also a type of TENORM, or technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material, that’s found throughout the oil and gas industry.

The health effects of radium exposure are extensive. A 1990 report by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) found chronic radium exposure led to cancers (mainly types of bone cancer) and death.

Grant’s Injection Ban May Have Avoided Potential Crisis

Four records included in the complaint file show water test results at the homes of the Yanity family where Pennsylvania General Energy’s Yanity 1025 injection well in Grant Township was permitted and then revoked because of the township’s ban.

There was no complaint record included, just water well test results for methane and minerals.

DEP’s violation database shows that in June 2021, the Yanity 1025 well was cited for “defective casing and cementing.” Two months later, DEP noted in a follow-up inspection that “PGE is required to submit a plan to remediate the issue but has failed to do so.”

Over a year later, violation records from October 2022 reveal that even though the Yanity well passed an EPA “mechanical integrity test” there was still gas migration and questions about casing integrity overall.

In the meantime, Grant Township may have avoided the contamination threats that prompted their ban on waste injection in the first place. By banning the injection well years ago and refusing to back down when taken to court, Grant prevented toxic, radioactive waste from being disposed into the Yanity well before structural problems occurred.

According to DEP, the Yanity well may still be permitted for waste injection in the future.

Public Herald’s documentary Invisible Hand covers the Yanity injection well fight in Grant Township.

Radioactive Waste Issues At Large

The 18 complaints provided by DEP for 2016 to 2021 only scratch the surface of injection well problems in Pennsylvania.

For example, buried in a 356-page document uploaded to DEP’s injection well website is record of Exco Resource’s waste fluid spill in Clearfield County at its Spencer Land #2 injection well. A faulty hose let loose 60 barrels of waste, and Exco’s spill containment failed to stop about 30 barrels of waste from flowing offsite, just uphill of Watts Creek.

Jenny Lisak was one of the Clearfield County residents who opposed local injection wells.

“Nobody in the entire community wanted [the] injection well and it was appealed multiple times,” Lisak said. “Not any of the citizens, not any of the powers that be, not our county commissioner, or township supervisors.”

On top of injecting radioactive oil and gas waste underground, Public Herald investigations have found that Pennsylvania allows industry to send inadequately treated waste to rivers and streams via landfill leachate and waste facility discharge.

Regulators also allowed road spreading of oil and gas wastewater called “brine” for dust suppression and de-icing for decades before being forced to place a moratorium on the practice. Research by Penn State University in 2021 found that, “[i]n Pennsylvania from 2008 to 2014, spreading O&G wastewater on roads released over 4 times more radium to the environment (320 millicuries) than O&G wastewater treatment facilities and 200 times more radium than spill events.”

These oil & gas waste methods permitted by DEP, and EPA, have introduced cancer-causing TENORM to waterways, groundwater, and the public that wouldn’t be there otherwise, driving radium to levels above background.

The situation with fracking wastewater disposal doesn’t appear to improve with injection wells, despite the bill of goods state and industry have sold to the public. And it may even be worse due to the fact that, once contamination reaches an underground water source, there are fewer remediation options, if any.

According to hydrogeologist Bob Haag, “Once a groundwater aquifer is contaminated, its useful life for drinking is over.”

New hope struck in 2017 that DEP would be held accountable for looking past pollution when PA Attorney General Josh Shapiro was elected to office. But after five years of investigating cases of water contamination, and a scathing Grand Jury report about DEP’s failures, the Attorney General has failed to hold DEP accountable.

“Everybody right now that’s in the DEP’s oil and gas management are liars,” Barr told Public Herald. “They’re really, really bad. They’re covering up, and they just cover up, cover up.”

Today, as Shapiro runs for governor, misconduct by DEP and industry seems all but forgotten during the campaign. The story remains, buried inside DEP’s records.

Jake Conley and Emma Lichtwardt contributed to this story.