Stopping Radioactive Water: Officials Want to Ban Oil & Gas Injection Wells at Pennsylvania Headwaters to Block EPA Permit

Stopping Radioactive Water: Officials Want to Ban Oil & Gas Injection Wells at Pennsylvania Headwaters

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

SUPPORT newsCOUP

Public Herald is a nonprofit newsroom that holds those in power accountable. You can receive our latest breaking stories by subscribing to our newsletter or becoming a Public Herald Patron.

by Sam Sanson for Public Herald

March 1, 2021 | Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers

March 18th update: a press release from CELDF (Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund) on March 17th states that residents from Clara Township, including officials cited in this article, started CCCT (Concerned Citizens for Clara Township) to establish Home Rule in the community. Nine members of the community are running to begin the government committee to explore establishing home rule in the township; seven could be elected in the May primary for the study commission.

March 31st update: the EPA has provided a list of all Class II injection well permits and their status in Pennsylvania (online data for this info has been consistently unreliable, or incomplete).

The Underdogs: Inspired by Grant Township, Clara Township Vows to Fight EPA’s New Waste Injection Well Proposal

Rolling green hills. Pristine waters. Vast, untouched space emanating peace and beauty. A long list of animals: grouse, deer, squirrels, chipmunks, foxes, beavers, and bears roaming. This is what you’ll find in Clara Township, three and a half hours northeast of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

caption: Kayaks on Oswayo Creek in Potter County during a storm at dusk — a scene from the production of the Triple Divide fracking documentary. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

When you zoom in to Clara, dirt roads appear. And between wide, tree-covered hills, houses pop up, where 181 people live in Potter County, 30 minutes from the New York State border.

Clara boasts untarnished waterways that provide far more than a sense of pride. Clean water in Clara is essential to local cattle, horses, wildlife, world-class fisheries, and residents who, without access to a public water system, all rely on wells or springs. Water from Clara pours out of the Appalachian Mountains as part of the Triple Divide: where rainfall splits from one mountain range to three sides of the country. Only four places on the continent have this kind of hydrological reach.

But there’s more than wildlife and farms in Clara. Hundreds of conventional and unconventional (a.k.a. fracking) oil and gas wells are cut into the landscape. And that means there’s oil and gas waste, too.

caption: Residual waste trucks carrying unmarked toxic radioactive fracking wastewater through downtown Coudersport in Potter County. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

In a rusty, grayish-blue building down a dirt road surrounded by trees and backed by beautiful mountains, sits Roulette Oil & Gas. It’s a 15-minute drive from Clara Township. The company operates 271 conventional and 3 unconventional oil and gas wells in Potter County.

Conventional wells are drilled vertically to reach shallow reservoirs of oil and gas. It’s a simpler and older process than unconventional, horizontal, hydraulic fracturing today, commonly known as “fracking.” Regardless of the well type, drilling creates large amounts of wastewater, that industry and regulators often describe with harmless names like “salt water”, “brine”, or “produced water.”

In September 2020, Roulette Oil & Gas submitted a permit application to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) which asks to convert one of their conventional wells in northwest Clara Township into a Class II-D injection well to dispose of brine from 110 of Roulette’s conventional wells in the area. That means shooting wastewater thousands of feet underground at high pressure into a cavern that once held fossil fuels.

A Public Herald review of EPA’s permit authorization for Roulette Oil & Gas found that it doesn’t exclude injecting waste from the three unconventional wells operated by the company. The permit allows for the injection of 15,500 barrels of wastewater a month (651,000 gallons per month at 42 gallons a barrel), and it can also be modified — leaving it open to accepting waste from more oil and gas operators in the future.

caption: Roulette Oil & Gas EPA permit authorization document.

Class II-D injection wells are not common historically in Pennsylvania as they are in states like Oklahoma or Texas where thousands exist. DEP’s website only lists 10 Class II-D permits for the whole state, one never being activated and currently revoked.

EPA senior media relations officer, Jeff Landis, sent a spreadsheet to Public Herald showing the total number of injection wells in Pennsylvania. It provided details on 5 new injection wells “under construction” in the state, on top of the 9 active wells listed on DEP’s website. All in all, EPA only manages 23 injection well permits for the Commonwealth.

That leaves very little public awareness or communication about injection wells.

Months after Roulette Oil & Gas submitted their request to the EPA, one of Clara Township’s Supervisors, Steve Mehl, found out about the permit.

“I’m thankful that someone did notify us because again, in my opinion, they were trying to, you know, do it under the radar. No one ever reached out to the Township. No one talked to us. So I don’t have a whole lot of respect for them. If I was a corporation or I was a business owner and I was going to do something in a township, I think common courtesy would say, yes, you would reach out to that township or the borough or whatever, and you present your case.”

Mehl told Public Herald that the threats posed by an injection well to the township’s groundwater is not a risk officials or residents are willing to take. EPA believes the waste is “unlikely” to contaminate groundwater.

DEP records from the past six years show Roulette Oil & Gas has reused their wastewater, stored it on site, disposed of it in pits, or sent it to Fluid Recovery Services Kingsley, a wastewater treatment plant located three hours east of Clara.

What’s not in those records or mentioned in the EPA permit is that oil and gas waste contains radioactive material.

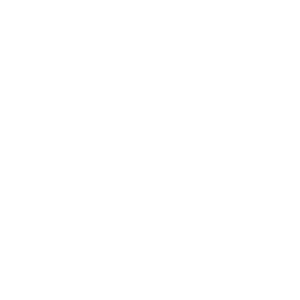

When you’re talking about oil and gas, you’re also talking about radioactive material, specifically TENORM (Technically Enhanced Radioactive Material). The main radioactive element inside of oil and gas TENORM waste is Radium-226.

Radium comes from uranium and to a lesser extent can be from thorium. It’s a cancer-causing element that has a half-life of 1600 years and decays into what is more commonly known as radon gas (specifically the isotope radon-222).

The uranium decay chain from the 2016 PA DEP TENORM Study Report. © PADEP

In 2016, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) finished a TENORM study and found high levels of Radium-226 in both conventional and unconventional waters. Every wastewater sample in the study exceeded the EPA limit of 5 picocuries per liter (pCi/L) for combined radium in drinking water.

caption: Radium detected in a very limited number of conventional wells for the 2016 DEP TENORM study.

Though oil and gas waste contains hazardous materials, it’s not considered “hazardous” by the EPA. In 1988, the EPA declared that even though oil and gas waste contains toxic heavy metals, carcinogens, and radioactivity, regulating the waste as “hazardous” would cause “a severe economic impact on the industry and on oil and gas production in the U.S.,” so it exempt the industry from hazardous waste law under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).

TENORM from oil and gas operations is also not covered by federal regulations governing radioactive material, including the Atomic Energy Act.

EPA’s permit for Clara’s injection well only requires testing the fluids every two years, and doesn’t list TENORM among the substances to be sampled. That leaves it up to the state, and Pennsylvania hasn’t created TENORM regulations for injection wells.

caption: Roulette Oil & Gas EPA permit authorization document only requires testing the fluids for a limited number of substances every two years, excluding radioactivity.

Water contamination from wastewater injection isn’t a sure thing, but the risk is. A 2012 investigation, “Injection Wells: The Poison Beneath Us,” by Abrahm Lustgarten at ProPublica found that, from late 2007 to late 2012, one in six injection wells had violations implicating the wells’ structural integrity. More than 7,000 injection wells showed signs of leaking.

In West Virginia, for example, in 2016 the United States Geological Survey discovered contaminants from an unconventional oil and gas waste injection well in nearby streams and sediments.

Clara doesn’t have to chance those odds, just yet. Laurie Barr, a community advocate and founder of the nonprofit Save Our Streams, is hopeful they will keep an injection well out of their community because the supervisors are united against it. Barr started an online petition asking the EPA to deny the injection well permit.

“When you have all of the officials in town unanimously wanting to fight this…with their support, that’s powerful,” Barr told Public Herald. And “it’s so important to protect the watershed. And that’s the main priority to me, is protecting the watershed.”

Supervisor Steve Mehl confirmed, “Unanimously, we are against a toxic waste injection well in Clara Township. And the main reason is because of the water.”

While exploring options for Clara Township’s fight, Supervisor Mehl said he recently found an ordinance from a decade ago, signed and dated by officials, that bans injection wells in Clara Township.

“What brought about that ordinance is another company was going to put an injection well in, and I’ve been told that they fought it and they won,” Mehl told Public Herald.

caption: In 1987 Clara Township passed an ordinance to stop injection well construction in their community.

If Clara Township fought an injection well in the past without enacting Home Rule, maybe they could do it again. Though, a township ordinance wasn’t enough for Grant Township. Grant tried that, as a “second class township” before it became a home rule municipality, but lost that fight in court. And the ordinance did more to hurt them then help. Their legal representatives ended up paying over $100,000 in legal fees to Pennsylvania General Energy.

Mehl says that the township is in this for the long haul and is considering enacting Home Rule Law which changes the way a community is governed. “All day long. Listening to all the material I got, first thing I said was, we need to look at Home Rule.”

Mehl heard about Home Rule from another community fighting an injection well: Grant Township. Their battle is featured in the new film INVISIBLE HAND, an award-winning Rights of Nature documentary directed by Public Herald co-founders Melissa Troutman and Joshua Pribanic, with Executive Producer Mark Ruffalo.

caption: In September 2020 INVISIBLE HAND, directed by Public Herald co-founders Joshua Boaz Pribanic and Melissa Troutman, was released with Emmy award-winning actor Mark Ruffalo as the Executive Producer. The documentary is the first feature film about the Rights of Nature movement, showcased alongside capitalism, and democracy. Since its release INVISIBLE HAND screened as ten official selections to international film festivals, winning four best documentary awards at independent competitions.

INVISIBLE HAND documents how Pennsylvania General Energy chose Grant Township as the injection well site for its wastewater, and how residents voted to ban it. Seven years later, there’s still no injection well.

In the process of doing so, Grant Township transformed from a second class township to a home rule municipality. In Pennsylvania, home rule gives a community more freedom to pass their own laws through local charters. It’s Grant’s Home Rule Charter that bans injection wells.

But Grant Township’s success isn’t set in stone. Once the home rule charter banned waste injection, DEP sued the township. And two months ago, Pennsylvania General Energy (PGE) filed its second lawsuit against Grant in the company’s multi-pronged attempt to overturn the ban on injection wells. PGE claims the Home Rule Charter is unconstitutional, that it violates the corporation’s constitutional right to do what it wants, where it aims to.

caption: Pennsylvania General Energy claims Grant’s Home Rule Charter is unconstitutional and unenforceable, putting into question any Home Rule Charter operating under Pennsylvania law, such as the one in Pittsburgh, Pa.

PGE also appealed the DEP’s 2020 decision to revoke the injection well permit it had previously issued. In a letter to Pennsylvania General Energy’s attorney, DEP Deputy Secretary of Oil and Gas, Scott Perry, wrote:

“Operation of the injection well pursuant to the Injection Permit …would violate a local law that is in effect… Specifically, Section 301 of Grant Township’s Home Rule Charter that bans the injection of oil and gas waste fluids.”

It’s the only time the Department has revoked such a permit. It set precedent that Clara Township hopes to repeat.

Pennsylvania’s Fight Against Injection Wells

Grant and Clara aren’t the only communities fighting injection wells.

Plum Borough, just outside of Pittsburgh, undertook a years-long fight against a Class II Injection Well. Despite widespread opposition from the town, construction began on the well in the fall of 2020 after attempts to use zoning and ordinance laws to stop the well failed. When asked why Plum didn’t pursue a home rule ban, a former supervisor said the borough’s attorney told them it was too late.

Clearfield County, which is home to four injection wells, also tried to fight. Resident Jenny Lisak told Clara officials about Clearfield’s latest waste injection site at a recent public meeting:

“Nobody wanted that injection well,” said Lisak. “Including all the elected officials, the county commissioners, the supervisors. And they appealed it three times. You can’t even believe what a bad idea it was. It was in a residential area. It was only yards away from the largest underground coal mine in Pennsylvania. But they approved it anyway.”

It’s no surprise Clearfield County is home to injection well skeptics. In 2012, an Exco Resources’ injection well in the county operated through mechanical issues for months resulting in a leaking underground pipe. Lisak noticed a problem at a spring near the site:

“The conductivity was sky high,” she said, “So I contacted the EPA. They said they would let the DEP know. About a month later I asked what the DEP did or said and they said they didn’t know, and it’s still bad [today].”

Dimock Township in Susquehanna County, made famous when Cabot Oil & Gas contaminated large sections of its drinking water aquifer, recently learned about the possibility of a Class II Injection Well coming to their community. After residents began organizing in opposition, the company backed off and gave up on the project.

Declaring war on oil and gas waste is not easy. Judy Wanchisn, mother of Stacy Long and founder of the East Run Hellbenders Society, was one of the key figures in Grant Township’s fight.

“I mean, I have so many papers, you can’t believe,” said Wanchisn. “It’s like my computer room, which is a bedroom, it’s full. All the dresser drawers and the cupboards and the closets. And I have stuff everywhere…My husband too, I think he’s ready to divorce me. I was like, stuck to that computer. In 2014, 2015, with research and you know, all that stuff it was like, oh, I’m sick of this computer.”

caption: Judy Wanchisn, founder of the East Run Hellbender Society, talks to Public Herald during an interview for INVISIBLE HAND. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic

To Wanchisn, there’s no other way. “You go til you can’t go anymore…if they take your water, your homes no good, especially where we live.”

The dedication and hard-work of residents like Wanchisn is part of the reason Grant has been able to keep an injection well out of their community all these years. Wanchisn’s son-in-law, Mark Long, said Grant’s solution was straight-forward.

“You know, gathering the people together in a room, explaining it to them and saying, ‘Do you wanna have a radioactive toxic waste dump in your backyard?’ And everybody said no,” said Long.

Sounds easy enough. But back in Potter County, Barr noticed various obstacles in getting the word of the injection well out to Clara Township residents.

“They don’t get notified the way we do… a lot of people out there, because it’s rural, don’t even have internet,” Barr said. “These people are being cut out of the equation because of the lack of internet in such a rural area.”

Barr found another issue with mobilizing Clara community members. Some are second home owners.

“There’s the people that are out of the area that don’t read the local newspaper because they don’t live here. But they still have a dog in the fight. They deserve to have their voices heard, their concerns addressed.”

These obstacles pushed Barr to request that the EPA extend their public comment period.

After pleas from community advocates including Barr and Mehl, the comment period has been extended to April 5, 2021. Comments can be emailed to EPA official Kevin Rowsey (email: [email protected] or by phone 215-814-5463).

On February 2, the EPA held the first virtual public comment hearing for the injection well permit in Clara. No in-person meeting has been scheduled, citing COVID concerns. After a brief introduction from an EPA official, members of the public took turns expressing their thoughts on the proposed injection well. Laurie Barr was there.

“My concerns base around the past waste management practices of Roulette Oil and Gas,” said Barr. “They have listed 101 times a storage disposal pending reuse. Um, this isn’t a waste disposal method. This isn’t this isn’t clear. What happened to the waste from these?”

Mehl was there too. “Based on historical data from the DEP database,” he told attendees, “Roulette Oil and Gas has a long history of violations and discrepancies.”

Most of the comments at the hearing were about drinking water.

In the first comment of the evening, Clara Township Supervisor Rob Wiley summed it up like this:

“My number one concern as a resident of Potter County, Clara Township, is the drinking water. And in the public notice that was sent out to Clara Township, it states the EPA requested public comment on its findings that the proposed injection activity under the draft permit is unlikely [to contaminate drinking water]. Using that highlighted word unlikely to pose a risk to the underground drinking water. I believe in using the term ‘unlikely’, there is a possibility or a likelihood of a leak or contamination.”

Throughout the hearing, concerned citizens emphasized a lack of trust in Roulette Oil & Gas and the Department of Environmental Protection, who is currently being investigated by the attorney general for their conduct in regulating the oil and gas industry.

Here’s Francis Weeks, a decades-long resident of Potter County who resides in Clara.

“In this industry, there exists a very long list of infractions, violations, fines, and penalties under permitted activities,” Weeks testified. “The public has no reason to believe that this project will be any different.”

Hearing attendee Dan Tomkinson shared similar distrust. “I have now taken to referring to the Pennsylvania DEP as the Pennsylvania Department of Oil and Gas Protection.”

At the end of the hearing, supervisor Wiley asked for a 90-day extension of the public comment period beyond the March 4th deadline.

“Due to COVID-19, as well as living in a poorly communicated area due to poor technology, lack of newspapers and just the overall situation that we’re dealing with.”

EPA will publish a response report addressing resident concerns and questions they’ve received at the hearing and from written comments once public comment ends . At that point, residents won’t be able to make further comments, but they can file an appeal within 30 days through EPA’s Environmental Appeals Board.

When it comes to the injection well permit being issued, hearings often carry little weight. At the end of the day, everyone in a town could show up, make rational points and be fully against it, but so long as the permit papers are filled out correctly, the EPA is likely to approve it.

Grant learned that lesson the hard way.

“The hearing is a farce,” said Mark Long. “You’re not going to get anything out of it except your local citizenry riled up if you can get the EPA to admit to the fact that their public hearing is a farce.”

“You can look up the stuff I said at the EPA hearing in 2014. It’s all still there. It doesn’t matter.” said his wife, Grant Township supervisor Stacy Long. “I raised the issue that everyone in Grant Township does not have access to public water. We all rely on a private well and springs. What happens if the aquifer gets contaminated? What’s to be done about that? And you know, they just, they stood up in the front of the room and nodded and it got written down. That was it. It’s, it’s a joke.”

“We were fixated on appealing the permit and getting DEP and the EPA to do their job,” Mr. Long added. “It took us a while to understand what their jobs really were, and their jobs were not protecting us, their jobs were shielding industry from risk.”

Square One

Laurie Barr is preparing for the next leg of the fight, against the DEP permit. Without it, Roulette Oil & Gas can’t start the injection well, EPA permit or not.

“So far, the DEP does not have a permit, on file with them,” she said. “And they explained to me that the DEP process…could be two years before they get a permit.”

Mehl thinks ahead, too. He contacted the DEP regional office.

“They don’t know nothing about it. They don’t have no permit blah, blah, et cetera, et cetera,” he told Public Herald.

Barr and Mehl are on top of it, but if Clara Township’s fight turns out like Grant’s, like the EPA, DEP won’t be much help.

Mark Long noted, “The Department of Environmental Protection in Pennsylvania isn’t. It’s the Department of Everything Permitted. Their job is not to protect the environment, it’s to issue permits and shield corporations from risk. And it’s the same way with the EPA. The game is rigged, and it is a game.”

Stacy Long recalled, “So, yeah, none of our local legislators came swooping in to save us. And offers to swoop in and save us are still six years later, forthcoming. That township knows what’s best for it and its people. And, you know, if they’re not afraid of going to court and sticking up from themselves and knocking on doors and gathering community support, then there’s no reason to not fight back.”

Clara Township agrees. They’re not putting all their eggs in the permit basket, not by any means.

“I do see that there’s a lot of options available,” said Barr. And Clara Township is open to considering Grant Township’s path to an injection well free town.”

The Long’s main piece of advice for Clara in their battle is simple – “don’t stop, and don’t be afraid to think outside the box.”

caption: Grant Township Supervisor Stacy Long talks to Public Herald about Rights of Nature and Home Rule Charters during an interview for the documentary INVISIBLE HAND. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

“When the lawsuits start coming in,” Stacy Long continued, “you can, like, take stock and that, you’re doing something right. The lawsuits are designed to stop and or intimidate.”

Not giving up is easier said than done.

“The people you’re fighting against are very much used to winning,” added Mark. “In fact, in Pennsylvania, they’re used to having a state agency give them a permit and they don’t have to fight at all. But if they do have to fight, they’re very much used to winning.”

Despite the challenges that may be ahead for Clara Township, Laurie Barr remains optimistic.

“It has a potential to be a long, hard battle,” said Barr. “I see it being a long battle, but I don’t see it being that hard. But, like, this is the very beginning.”

Joshua Boaz Pribanic and Melissa A. Troutman contributed to this story