Senator Says Pennsylvania Bypassed Feds & Issued “Illegal” Permit That Threatens Dimock Waterways With Radioactivity From Fracking

Senator Says Pennsylvania Bypassed Feds & Issued “Illegal” Permit That Threatens Dimock Waterways With Radioactivity From Fracking

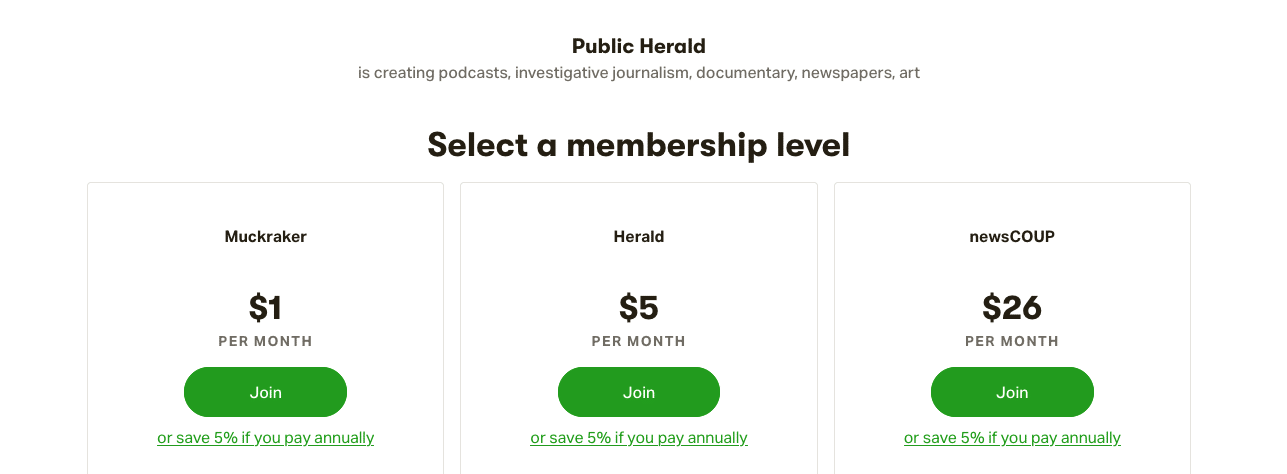

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

by Jake Conley, Melissa A. Troutman and Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

August 29, 2022 | Project: newsCOUP, Radioactive Rivers, TENORM Mountains

NPDES Permits – Part One, Dimock Pa.

Matt Neenan’s dairy farm in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania has been active for 120 years.

“Children for generations, including my own, have played in the woods and waters of this land,” he wrote in an affidavit filed in March 2022 with the Pennsylvania Environmental Hearing Board.

Neenan and about 40 other residents of Dimock Township, where water contamination from oil and gas fracking has polluted homes for years, submitted affidavits opposing a new plan to treat toxic oil and gas waste laced with radioactive material and dump the leftovers into two creeks – the same two creeks that Neenan’s cows drink from.

Dimock has already suffered water contamination from oil and gas fracking operations for more than 12 years. Residents who once had good well water still rely on water deliveries to their rural homes, paid for by Cabot Oil & Gas, the company blamed for contamination. Cabot never admitted wrongdoing, silenced impacted residents with gag orders in exchange for drinkable water, and now has criminal charges levied against it by Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro.

Dimock residents’ affidavits are part of an appeal filed by Pennsylvania Senator Katie Muth (D-44) that attempts to overturn a permit that authorizes Eureka Resources, a company that claims to “cleanse” fracking waste, to discharge the treated fracking waste to the creeks.

Despite its claims, some of Eureka’s discharges have tested positive for high amounts of radium — a highly radioactive, cancer-causing element found in oil and gas waste. The permit requires Eureka to test for radium only once a week and does not set a limit on the amount of radium the company can discharge into waterways.

caption: Eureka Resources Standing Stone facility in Wysox, Pa. © Joshua Boaz Pribanic for Public Herald

Senator Muth told Public Herald that the plan for Dimock is “environmental injustice” perpetrated by the Commonwealth’s own Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

“This community has been – they’re the sacrifice zone,” Muth told Public Herald. “So I couldn’t just say, sorry, not my problem, I don’t represent you, have a great day.”

The threat of more pollution in an area that’s already suffering is reason enough to appeal the permit, but there’s an even bigger reason, Muth said. She says that DEP’s approval of the permit was “fraudulent” from the beginning.

caption: State Senator Katie Muth (blue striped suit) listens to Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf in Harrisburg, Pa. Muth says the Governor’s DEP bypassed an EPA review and issued an illegal NPDES permit that would allow radioactive treatment of fracking wastewater to be discharged to creeks in Dimock. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

DEP’s permit to Eureka is part of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, or NPDES program under the Clean Water Act* which aimed to eliminate “the discharge of pollution into navigable waters…by 1985.” Unfortunately, instead of ending pollution of waterways, the NPDES permitting system actually prolongs it.

In Pennsylvania, the NPDES program is managed by DEP officials, but Eureka’s permit, like all permits of its kind, also requires federal oversight by the U.S. EPA.

According to Senator Muth, the EPA was unaware of Eureka’s permit until she brought it to their attention – after DEP already issued it.

“The EPA never saw this application until I brought it to their attention…meaning, DEP gave [Eureka] a fake permit,” Senator Muth told Public Herald.

On public record, on at least three occasions, DEP claims it secured a waiver from EPA, which skipped federal approval. But, Senator Muth said, EPA officials told her they’d never seen the permit let alone issued a waiver.

In emails with Public Herald, the EPA confirmed it never received the permit for review from the DEP — even though this type of permit “should have been sent to the EPA,” according to the agency.

In a phone call with EPA, Senator Muth asked if staff at DEP knew which permits required EPA review.

“They said yes, but they said that this was an operational error. That someone, whoever uploaded the permit on DEP’s end, clicked the wrong box. And they never saw it.”

But Muth is suspicious. Perhaps it’s because, since modern fracking started in Pennsylvania around 2005, countless residents have claimed illness and loss of their drinking water. Or perhaps because DEP has been reprimanded repeatedly by the likes of Pennsylvania’s Auditor General and an Attorney General Grand Jury for failing to protect the environment and frontline residents.

Plus, the EPA waiver isn’t just cited in one place. It’s been “typed out” several times.

“There are three separate documents on DEP’s website, two draft, one final, stating that they obtained an EPA waiver,” Muth added.

So Senator Muth amended her appeal in March, adding that DEP “failed to follow the NPDES permit review process required by US EPA Region III and approved a permit that the Department does not have the authority to approve, and that is not eligible for a waiver by US EPA Region III.”

She and the residents of Dimock await the Environmental Hearing Board’s decision.

The criminally-charged Cabot Oil & Gas, now known as Coterra, is one of the companies whose waste Eureka will be processing in Dimock.

NPDES = Permission To Pollute

Radium is not a required part of testing and monitoring under the federal NPDES program. But the federal government gives states the authority to place additional limits on pollutants above and beyond federal standards. This includes limits on radium, which is a carcinogenic radioactive element in almost all oil and gas waste.

But a Public Herald review of NPDES permits revealed that Pennsylvania DEP rarely chooses to set thresholds for radium, despite their knowledge of high levels occurring in fracking waste.

Eureka’s NPDES permit for Dimock is one of these situations.

This, Muth explains, isn’t just a problem for Dimock.

“If it can happen in Dimock, it can happen anywhere, and it is happening,” she said.

“Our watersheds are interconnected. What is allowed to happen in one crick, means that it can happen in another fucking crick.”

caption: Senator Katie Muth sits on the bank of the Susquehanna River in Harrisburg, Pa. that makes up part of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Part of the problem, according to EarthJustice attorney Megan Hunter, is that the decision-making used for permitting is flawed from the start.

Hunter told Public Herald that the NPDES permitting system operates on two main premises – the first is water quality standards. The problem with that concept, she explained, is that water quality standards have only been created for certain pollutants.

“It’s not like we have water quality standards for every pollutant possible out there,” Hunter said. “Things are going to fall through the holes that are indeed harmful.”

Fracking Waste Treatment Systems Fail to Eliminate Radium

A key part of this story is that Eureka’s patented process seemingly fails to remove cancer-causing radium from the waste it purports to “cleanse.”

Eureka already operates two other facilities in the state for treating fracking waste: one in Williamsport (Lycoming County) and another in Standing Stone (Bradford County). The one in Standing Stone includes an NPDES permit for direct discharge to public waters.

At Standing Stone, DEP again failed to include radium limits in Eureka’s NPDES discharge permit. There, Eureka discharges directly to Towanda Creek, a tributary of the Susquehanna River.

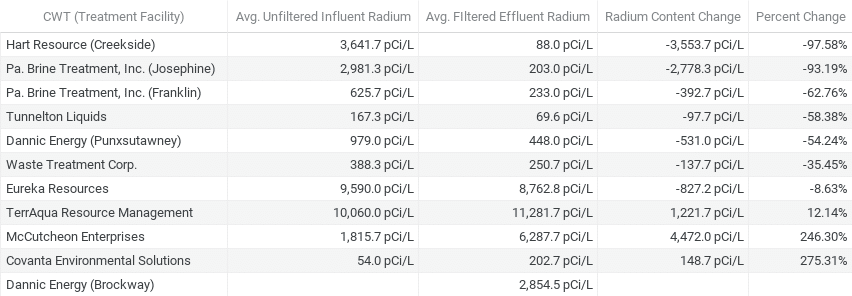

In January, Public Herald reported that DEP’s own data reveals that Eureka’s treatment process only removed about 9% of radium from the oil and gas wastewater it processed at its facility in Williamsport, PA.

At Eureka’s Williamsport facility, wastewater has entered the treatment system “hot” at an average 9,600 pCi/L of combined radium. After treatment, it’s tested only marginally less radioactive at an average 8,800 pCi/L of radium. These results are a far cry from “pure water” that Eureka claims to create, or the federal drinking water limit of 5 piC/L.

Chart: A comparison of radium levels in unfiltered influent (raw waste) vs. filtered effluent (treated waste) in centralized wastewater treatment (CWT) facilities. No radium test results for unfiltered influent at the Dannic Energy (Brockway) CWT were provided in the DEP’s TENORM study. Eureka’s process only removed 8.63% of total radium. Read more in Public Herald’s TENORM Report.

Despite this evidence that Eureka only removed a fraction of the radium, DEP allows the Williamsport facility to send its “treated” fracking wastewater to Williamsport Sanitary Authority Central (WSAC), which then passes Eureka’s wastewater through its sewage treatment system – which does not remove radium.

The Sanitary Authority then dumps the wastewater into the Susquehanna River under its own NPDES permit, also granted by DEP, which does not set a limit on the amount of radium dumped into the river either.

Since its founding in 2008, Eureka Resources has crafted an image as a company that breaks industry molds. It lauds itself for blazing a trail for fracking wastewater treatment, and its vice president of engineering told Public Herald in 2018, “It’s all focused on, you know, generating the cleanest product that can be used for as many things as possible.”

Public Herald found in 2018 that Eureka was taking the salt leftover from its treatment process and selling it to the likes of Clorox, which has used the fracking waste byproduct as pool salt in major department outlets such as Walmart, Lowes, and Home Depot.

caption: Eureka Resources’ website claims to return water to “its natural state” and meets all federal and state “standards for pure water” without mentioning that radium levels in DEP’s 2016 study from Eureka’s treated water were more than 1000 times above the federal drinking water standard.

For Hunter, technology poses another problem within the NPDES permitting system which asks, ‘What can the technology do?’

When regulators look at the problem through the lens of technology, Hunter says, they’re not thinking about what the ecosystem actually needs. Instead, it’s about the best that polluters can do given “available technology.”

For the residents in Dimock, and all across Pennsylvania, the best available technology doesn’t guarantee clean water. Still, the least DEP and EPA could do is set hard limits on the toxins they know exist, like radium.

Fracking Radioactivity

Radium is a cancer-causing element with a half-life of 1,600 years. In Pennsylvania, radium has already created problems for waterways that serve as dumping grounds for oil and gas waste.

Studies have documented the accumulation of oil and gas waste radium in stream sediment, radium toxicity from road spreading of oil and gas wastewater, and the increased risk of leukemia in children who live closer to fracking operations.

In its own 2016 study, DEP found radium levels in Marcellus Shale oil and gas waste up to 26,000 picocuries per liter (piC/L).

In 2014, oil and gas waste from PA was so radioactive, it was rejected by a facility in West Virginia. A 2015 study published in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Health Perspectives found that radioactivity in oil and gas waste can increase (referred to as “ingrowth”) over time under some conditions, and that estimates of the total amount of radioactive material in the waste can be inaccurately underestimated.

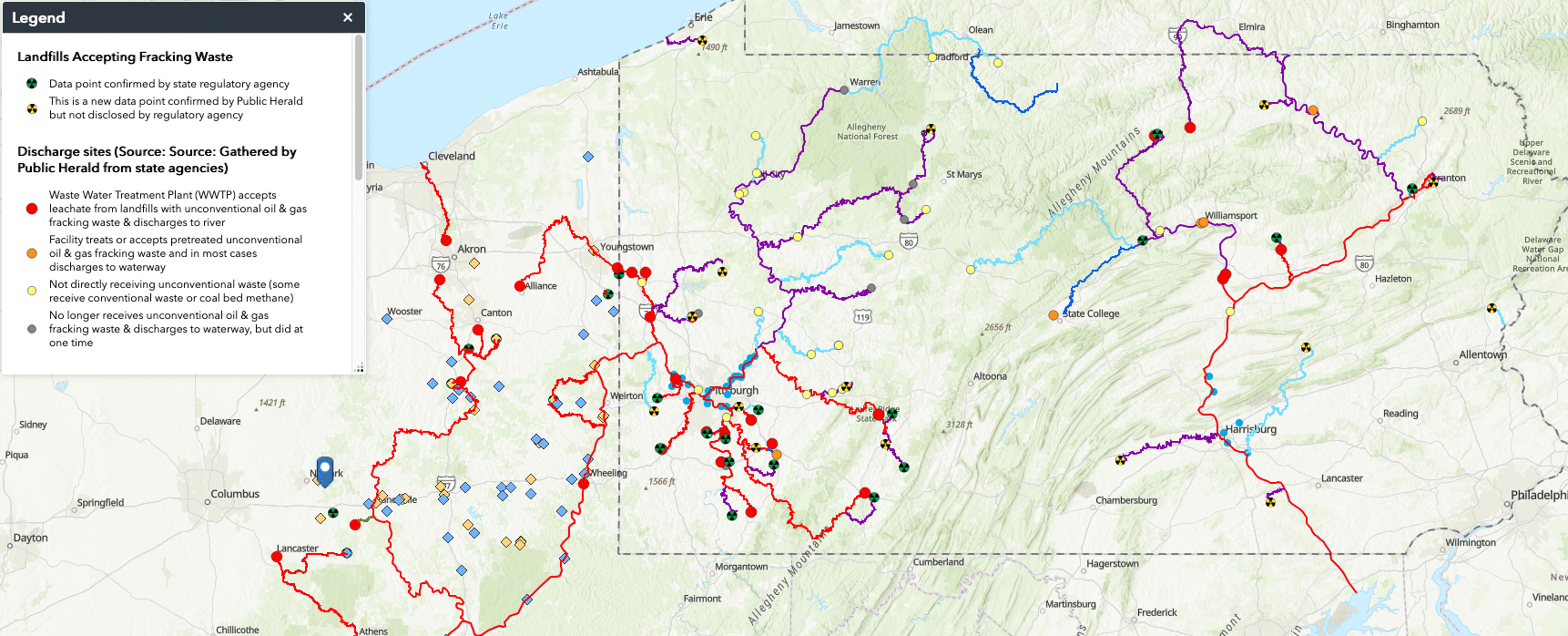

In 2019, Public Herald mapped where radioactive oil and gas waste is passed through public wastewater plants into Pennsylvania rivers without proper treatment.

caption: Public Herald’s TENORM Leachate Map illustrates where (in red) radioactive waste from fracking is escaping into public waters, and where (trefoil symbol) it’s being stored in Pennsylvania. The 2019 report discovered a statewide system of TENORM being released from landfill leachate to POTWs, and the investigation was updated in 2020 with a new map. Click for interactive map »

And in 2022, Public Herald mapped the names and locations of radioactive test results from DEP’s 2016 study of oil and gas radioactivity. Until Public Herald’s report, the names and locations of radium test results had been withheld by Pennsylvania officials, keeping company names that were tied to radium discharges like Eureka’s hidden from the public.

Despite decades of documentation and scathing reviews by Pennsylvania’s Auditor General and Attorney General, DEP still does not use its authority to set limits on radium from oil and gas waste in NPDES discharge permits.

When asked if DEP could require radium monitoring for facilities like Eureka’s, EPA responded via email, “[M]onitoring for those constituents is not required under the federal regulations. However, state permit writers can require additional monitoring in permits issued to specific direct discharging facilities.”

In other words, the Pennsylvania DEP could be eliminating the threat of radium in waterways. They’ve simply been choosing not to.

Muth’s “Hail Mary”

Senator Muth, who owns a home on the Susquehanna River and is concerned for residents in the Dimock “sacrifice zone”, says she just happened to see that Eureka’s NPDES permit had been granted while looking for something else. She appealed it in the knick of time.

“I file [the appeal] as a hail mary, with all these residents’ affidavits,” said Muth. “At first we’re appealing it because it’s bad, right? It’s environmentally unjust. Then documents are posted, because during this appeal period, the DEP’s eFACTS was down, for like three weeks, under ‘maintenance’. So I only had certain documents that were available online, where others were later uploaded.

“And then, you [Public Herald] publish [the TENORM report] in January that said, here’s all these places from the TENORM study that we got through the Right-to-Know battle. Nobody could have done the public comment from November to December of 2021 and had that information you guys published, because it wasn’t public.”

caption: PA Senator Katie Muth talks about her NPDES lawsuit in Dimock at her office in Harrisburg. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Sen. Muth also told NPR that no one in Dimock could have known Eureka’s effluent levels of radium until the Public Herald report released in January, after the public comment period for Eureka’s permit had already ended.

The radioactivity at specific locations of fracking wastewater discharges, including Eureka’s, was unknown before Public Herald’s January investigations, which have mapped and revealed systemic negligence by state and federal governments to properly protect rivers and people from fracking waste discharges.

Senator Muth is now using the data in her appeal.

According to Muth, the Pennsylvania Environmental Hearing Board is split on whether or not they’ll allow her case to continue based on standing. Meanwhile, the lives of Neenan the dairy farmer, and all of Dimock’s other residents, hang in the balance.

“They should just restart the whole process,” Muth told Public Herald. “If EPA didn’t [see the permit or issue the waiver] they should start from scratch, review the permit, hold public comment. Then we’d have more time to make the public aware, and maybe someone else could intervene who had better standing.”

So far, sources in Dimock say Eureka hasn’t begun construction of its planned facility.

The DEP refused to comment about the appeal, citing the advice of its legal counsel.

Pennsylvania’s Permits to Pollute

Once Senator Muth found out the EPA never issued the waiver for Eureka’s permit to discharge, it made her wonder:

“How many other places is this happening?”

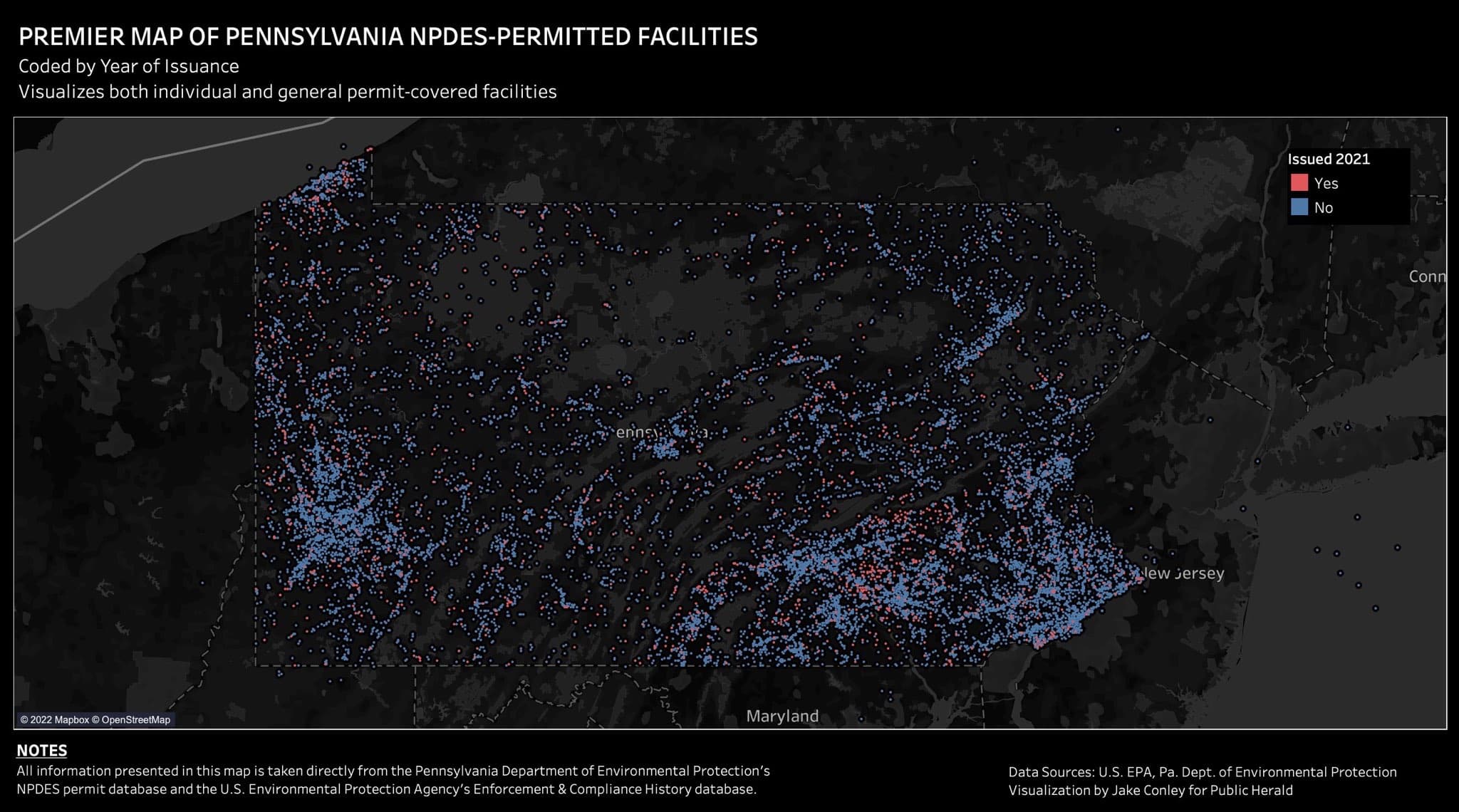

Wondering the same, Public Herald started a laborious journey in 2021 toward this answer by mapping all of the NPDES permits issued in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The map doesn’t tell us yet how much radium or other toxins are being dumped into rivers, or whether more EPA “waivers” are illegitimate – that will require months or years of more research.

What the map does show is how pervasive the NPDES “permit to pollute” is issued across the Commonwealth. What’s actually coming out of the facilities with NPDES permits, and whether DEP issued them correctly, is another question.

caption: All data is based on an aggregation of what’s published by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Geospacial data is taken from the EPA’s ECHO database. Any incongruencies between EPA and PADEP data are the result of data mismatches noted by the EPA here: https://echo.epa.gov/resources/echo-data/known-data-problems#PAalerts. Where applicable, EPA data has been given precedent. Note, individual data points may be difficult to navigate on the map from Tableau. Instead, we recommend viewing the data used for the PA NPDES permit map.

Since 1999, the number of waste discharge permits issued in PA has hovered between the upper 1,000s and lower 2,000s.

But in 2021, the DEP, under Governor Tom Wolf, granted 3,068 permits according to data provided to Public Herald. The DEP’s database lists 10,494 total active NPDES-permitted facilities in Pennsylvania.

The NPDES System Legalizes Harm

When it comes to oil and gas radioactivity, which regulators call Technologically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (TENORM), the EPA itself presents a daunting message:

“Although EPA and others working on the problem have already learned a great deal about TENORM, we still do not completely understand all the potential radiation exposure risks it presents to humans and the environment.”

Currently, the NPDES permitting system obfuscates and legalizes radioactive pollution by not explicitly limiting the amount of TENORM that facilities like Eureka Resources can discharge to waterways.

With neither the national EPA nor state governments requiring such limits, there appears to be no accountability for oil and gas radioactivity within the NPDES system at any level of centralized government. Instead, the radioactivity problem is created, continuously obscured, and legitimized by the NPDES system.

With regard to DEP failing to limit Eureka’s radium discharge to waterways, Sen. Muth said to Public Herald, “I think it’s a criminal act of the government to not require that — that’s gross negligence.”

When it comes to DEP, negligence when regulating oil and gas waste seems to be a systemic problem. In 2017, Public Herald found widespread negligence and other misconduct on the part of DEP officials during drinking water contamination investigations.

In 2021, Public Herald found that NPDES-permitted facilities have a history of non-enforcement and lack of proper regulation. At the Keystone Sanitary Landfill in Lackawanna County, for instance, 224 complaints about the landfill had been filed with the DEP over 34 years — yet not a single complaint resulted in a penalty or enforcement measure by the DEP.

Back In Dimock

One of the affidavits filed in Senator Muth’s case from resident Nolen Scott Fry reads: “We the residents have little faith in our DEP to protect our waterways due to past experience of not holding the gas industry accountable for its polluting across our counties.”

Neenan, the dairy farmer whose livestock drink from the tributaries that Eureka wants to dump wastewater into, wrote in his affidavit, “This farm is my life’s work … The only real goal I have is to continue to work this land and pass it along debt free to the next generation, so they can have it better.” [sic]

In her amended appeal, Muth writes: “The proposed location will be in a community plagued with legacy pollution from negligent oil and gas companies who continue to exploit the land and natural resources for profit and decimate ground water and private wells used for resident drinking water supplies for over twelve years.”

Eureka Resources told Public Herald in 2018 that the company operates “as transparently as we possibly can.” But Public Herald’s emails and phone calls to Eureka’s CEO Dan Ertel for comment on the new Dimock facility were never returned.

***

*Clean Water Act (Federal Water Pollution Control Act), aims to eliminate the discharge of pollution into navigable waters (by 1985) and prohibit “the discharge of toxic pollutants in toxic amounts.”:

(1) it is the national goal that the discharge of pollutants into the navigable waters be eliminated by 1985;

(3) it is the national policy that the discharge of toxic pollutants in toxic amounts be prohibited;

Historical context & acknowledgement:

The encroachment of industrial development, and the inevitable impacts to water, land, air, and community, are nothing new to families living in ‘resource extraction zones’ across the globe. It’s certainly not new to the native people of the Americas, who have lost and are still losing their clean water and air, their land and community, their culture and people to industrial colonization – far longer than anyone else in what is now called the United States.

Dimock Township in Susquehanna County is the ancestral home of the Susquehannock, Haudenosaunee, and Munsee Lenape people who were driven from their homelands.