Public Herald 30-Month Report Finds DEP Fracking Complaint Investigations Are “Cooked” & Shredded

In the largest release of fracking records in Pennsylvania history, Public Herald finds Water Contamination Investigations are “Cooked” & Shredded

by Joshua B. Pribanic & Melissa Troutman for Public Herald

Nearly 40 days after losing her drinking water, Christine Pepper received a certified determination letter from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) at her home in Leroy Twp., Bradford County. The letter would tell her whether fracking was to blame.

Halfway down the first page it read “analytical results do not reveal any impacts from oil and gas activity” meaning the DEP investigation for Complaint #302587 determined the drilling and fracking next to her home did not impact her water supply. According to the state, the drinking water that nurtured her family’s farm for over 50 years was still safe.

“The Department considers this case closed and does not anticipate any further action in relation to this matter.”

As DEP and industry advocates like Energy-In-Depth and Marcellus Shale Coalition have reiterated, most water contamination complaints receive the same letter as Christine and are determined by regulators to be “non-impact” cases.

Yet, until this report, the public’s never seen complete non-impact complaint records for multiple counties – and the story they tell is alarming.

After a 30-month analysis, a Public Herald investigation has uncovered 9 ways that officials at the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) have kept drinking water contamination across Pennsylvania “off the books” since fracking began in 2004.

That DEP has failed to make water contamination a matter of public record isn’t new, as revealed by private lawsuits where the Department admitted to walking away from documented contamination without issuing an order, notification or fine. Similar to patterns discovered by Public Herald, the Harvard Law School’s May 2014 report concluded that the most common errors in DEP’s water contamination investigations were:

- PADEP does not explain the water sample analysis;

- PADEP does not explain how it reached its conclusion;

- PADEP indicates that it does not have adequate information to make a determination;

- the letters are confusing and/or inconsistent with others in the same geographic area.

In drawing these conclusions, Harvard looked at 450 determination letter case files. Public Herald has now released 2,309 complaint records for 17 of 40 counties where shale gas operations take place, and our team has analyzed over 200 complaint cases.

Public Herald’s analysis concludes that the current 260 positive water contamination determinations listed by DEP is repetitively understated. Analyzing five key townships — Delmar, Charleston, Cogan House, Leroy and Wyalusing — Public Herald found the Department mishandled a significant percentage of its water contamination cases between 2009 and 2012. We refer to these cases as “cooked,” meaning there’s reason to believe that DEP’s determination can be challenged and possibly reversed.

The majority of the records, 1275, are complaints about drinking water, while the remaining 1034 cases are considered general complaints but can also be water related.

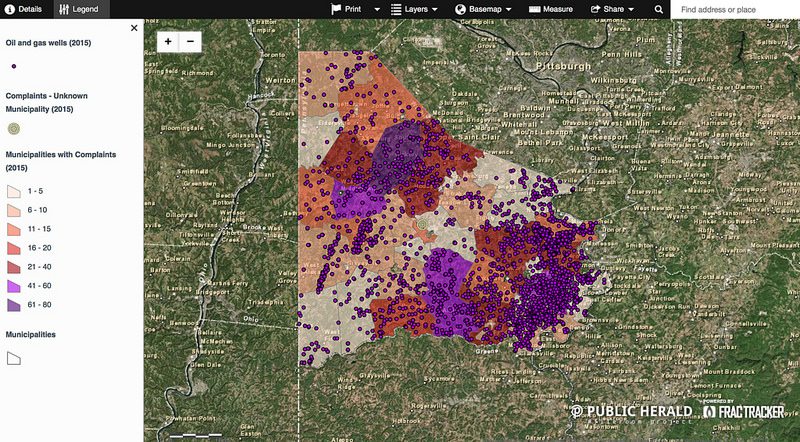

Washington County recorded the highest number of complaints at 667 cases, while Bradford County had the second highest of 520 on file with 398 cases being drinking water investigations.

Map of 667 PADEP fracking complaint investigations for Washington County. © Public Herald

Complaints Are The Road Map

In 2008, complaints served as the first road map to potential water contamination from fracking when residents in Pavillion Wyoming contacted EPA saying their water had been contaminated. These anecdotal phone calls and emails set the stage of doubt about the safety of ‘high-volume hydraulic fracturing of unconventional wells for shale gas’ — that came to be more simply known as ‘fracking’ in November 2010 (according to Google Trends).

What Are Complaints?

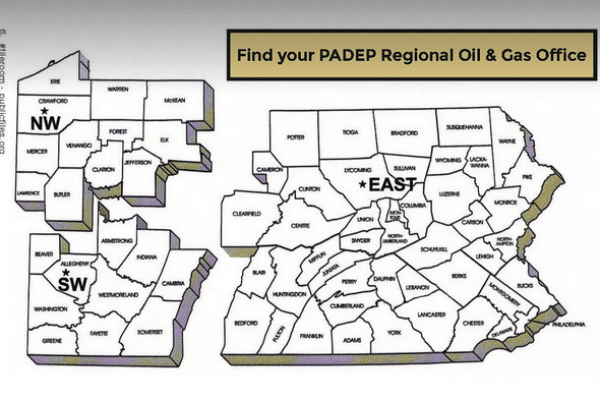

Citizen “complaints” are reports made to the state by residents — the “911 call” — that can range from water problems or violations at a well pad, to any number of observed concerns. Complaints are filed at one of three regional DEP offices, and largely dictated by Section 3218 of Chapter 58 of Act 13, the state’s latest oil and gas regulations.

Even though fracking for shale gas in the Commonwealth dates back to 2004, the Pennsylvania story of water contamination has never been completely told. And it couldn’t.

Early on, the DEP made sure that citizen complaint records were withheld from public view. Right-to-Know requests submitted by the likes of Earthworks, Public Herald, and more were all being denied using exemptions in the Right To Know Law.

In 2011 Public Herald’s first informal file review request to DEP for complaints never produced a single document. Then in 2012, Public Herald’s Melissa Troutman learned that complaints were being held as ‘confidential.’ When she asked why, an attorney from DEP’s Southwest Regional Office told her DEP Deputy Secretary Scott Perry didn’t want complaints to ‘cause alarm.’”

Without all of these records, fracking’s darker story of water contamination could only be marginally understood.

But later in 2012, DEP was nailed for transparency failures when it lost an open records lawsuit with the Scranton-Times Tribune for all the determination letters the Department had on file — which DEP claimed were either confidential or impossible to assemble. Times-Tribune published 969 determinations it received from DEP. But as Public Herald discovered, not all complaint records end in a determination (See Cogan House Twp. story below), leaving even more citizen complaints off the books.

Nadia Steinzor of Earthworks, unable to get access to complaint files, had this to say, “A good DEP staff person at the Northcentral office called me to explain that the [Earthworks] request was too broad and difficult to fulfill because different offices handle and maintain complaints differently.”

However, while DEP was telling Earthworks their request for complaint files couldn’t be produced, Public Herald was scanning those same documents.

“Our request was based on the assumption that DEP had a comprehensive system to consistently track and document complaints,” Steinzor explains. “But in the course of our research for the Blackout report, it became clear that this was a false assumption.”

Nothing at DEP file reviews came easy.

“Your demands don’t give up at all,” DEP Clerical Supervisor Ashleigh Scarbrough told *Public Herald during a 2014 review. “It’s like you want to come in now until the end of eternity every Monday, and we just can’t keep up with it.” At the time DEP’s file clerks were trying to reduce the number of files provided to Public Herald from whole counties to only eight townships per visit.

“You’re kind of on the cutting edge of asking for things,” said DEP Regional Director Marcus Kohl. “It makes it more difficult for us to be prepared for that…” he explained as to why complaint records would take longer to produce since the agency had never had to redact the files for public use. To Mr. Kohl’s credit, a negotiation was reached that day that cut out at least an extra six months of file reviews in the North Central office of Williamsport, PA.

Using persistence, threatening a lawsuit, and at one point holding a standoff with one of the office’s regional directors, it took just over two years before our File Team would be able to walk out with all the complaint documents for 17 of 40 counties with shale gas.

The results, Public Herald has now released 2,309 DEP complaint records in an online, open-source project called #fileroom (PublicFiles.org), where interactive maps built by FracTracker Alliance are searchable by county and township. All files can be viewed, printed and shared. This cumulative data comprises the largest ever release of fracking water contamination data from Pennsylvania.

The Cooked Complaints

“We have to be led by science.” “We have to rely on science.” John Quigley, Secretary of DEP in Senate Hearing on PA budget for DEP in March 2015, speaking on the safety of the Susquehanna River.

Cooked cases were initially reported by Public Herald in the documentary Triple Divide, where DEP turned a blind eye to baseline testing. During the 2011 Atgas blowout investigation in Bradford County, Chesapeake Energy was allowed to dismiss their own pre-drill water test results to avoid liability for contaminating a water supply. This simple act by DEP essentially changed the background water quality data for the area, creating an artificial history of drinking water quality.

Triple Divide prompted further questions for Public Herald, such as whether this type of willful negligence by both the operator and state happened more frequently. By the time records in each of the five townships were analyzed for this report, 9 methods for cooking complaint investigations became clear.

1. Baseline data from predrill water test results is dismissed. Postdrill water tests become the baseline or ‘norm.’ DEP issues a “non-impact” determination despite documented changes in water quality before and after drilling. The first of these cases was uncovered in Triple Divide. This changes local water quality history. Predrill tests are essentially thrown out.

E.G. 281502 (Wyalusing Twp., Bradford Co.) – methane levels go from around 8mg/L in resident’s predrill to 40mg/L in postdrill, an explosive change in methane levels (28mg/L is an explosion hazard in a home.) DEP determines methane is “ related to background conditions and concludes “non-impact.” DEP does not provide an isotopic analysis of the methane to identify the source. Additional cases in the neighboring Leroy Township did receive positive determination letters from DEP having similar methane changes and levels in their water supply.

E.G. 274235 (Delmar Twp., Tioga Co.) – no predrill test is provided. DEP is told by the gas company that an isotopic test showed the gas in the water supply was thermogenic (signifying it came from deeper, shale gas formations). However, DEP issued a non-impact letter after 16 months of investigating stating it does not “appear” gas well drilling is to blame.

E.G. RW04 (Leroy Twp., Bradford Co.) – no complaint record on file [Watch Triple Divide “Shoveling Water” re: Atgas well blowout; Read the story here.]

predrill test (n.) – a water test conducted by a certified laboratory at a private water supply before nearby drilling or fracking; used to document baseline water quality in the event of underground water contamination related to oil and gas operations.

postdrill test (n.) – a water test conducted by a certified laboratory at a private water supply after nearby drilling or fracking; used to compare to predrill water test results to determine whether oil and gas drilling or fracking operations have contaminated a drinking water source.

2. DEP cites postdrill water tests as if they are predrill test results. DEP uses water tests taken after drilling within one mile of the complaint as predrill.

E.G. 286764: DEP cites a predrill test that is taken after drilling has occurred in the area. The predrill used by DEP for its determination was conducted prior to drilling of one well pad (Nestor pad in 2011) but after the drilling of another (Stock 144 pad in 2008). Complaint records show the Stock 144 well illegally buried a waste pit that had to be removed. Public Herald talked to Charles Stock, landowner of the Stock 144 well, who confirmed that the Stock 144 well pad had welding problems during the initial casing and drilling. Charles Stock also has water quality problems related to the gas well on his property, but negotiated with the industry off public record. (Delmar Twp., Tioga Co.)

predrill (n.) and postdrill (n.) = not the same thing; see definitions under 1. above

Charles Stock tells Public Herald about water problems at his farm in Delmar Twp. and how he’d rather let the industry handle it. He’s pointing to the Stock 144 well pad cited in this report. © Joshua B. Pribanic for Public Herald

3. DEP issues non-impact determination letters to neighbors of residents with positive determination letters, typically after long, drawn out investigations. Residents who experienced water changes at the same time, usually within the same one mile radius, receive different determinations from DEP.

E.G. 302442 (Donegal Twp., Westmoreland Co.) – Nick Kennedy, Esq., the Community Advocate of Mountain Watershed Association, calls out DEP for failing to conclude contamination in a water well after DEP previously found a fracking company responsible for two neighboring contaminations of the same kind. [Public Herald has not yet retrieved Westmoreland County records, due 2016.]

E.G. Sugar Run GMI (gas migration investigation) (Wyalusing Twp., Bradford Co.) – Two water supplies receive positive impact determination and 21 other water supplies with similar problems in close proximity/time are issued non-impact determinations.

determination letter (n.) – letter sent by DEP to a resident stating whether drilling, fracking, waste storage, waste transport, or any other oil and gas activity is the culprit of sudden drinking water problems.

4. DEP “kicks the can” – DEP is aware that contamination related to oil and gas exists but sends the concern to another department, consequently keeping these cases off the books.

E.G. 279494 (Charleston Twp., Tioga Co.) – complaint shows signs of contamination from BTEX compounds at levels far above the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) safe for human consumption. But, the case is moved out the of complaint program and sent to the Environmental Cleanup Program (ECP). No determination letter can be found in the record.

E.G. 279262 (Leroy Twp., Bradford County) – complaint is part of Atgas blowout from April 2011 and has been pushed to the Environmental Cleanup Program (ECP). Even though complaint states water conditions met MCL according to an August 2011 test, it implies there were problems associated with the well which resulted in a temporary impact, which in other cases has resulted in a positive determination letter.

E.G. 273912 Complaint shows signs of problems and goes through a year of testing then state it’s “referred to the Program Geologist for additional evaluation” and falls off the radar. (Charleston Twp., Tioga Co.)

5. DEP uses the Presumption of Liability section under Act 13 to dismiss the complaint, basing their conclusion on a loophole in law rather than documented evidence of water contamination, i.e. the complaint came more than 12 months after drilling, or the complaint was made from more than 2,500 ft. from a well.

E.G. 275802: “The Judys” – DEP looked past documented water contamination to determine that a fracking company was not responsible for the contamination because the water well user, Judy Eckert, made the complaint about her water more than six months after the neighboring Marcellus gas well was drilled. (Roulette Twp., Potter Co.)

E.G. 290934: In the complaint DEP states, “Although there appears to be some fluctuation in several parameter concentrations, the 2012 results indicate better water quality than the 2011 sample. Although the complaint was received within a year of drilling and stimulation activities at the Broadbent 466 well site, the location of the water supply is beyond the presumptive distance.” However, DEP previously issued a positive determination letter in the same township for water contamination caused by a well pad a mile away from the complaint, which would put it well beyond the presumptive distance. (Delmar Twp., Tioga Co.)

presumption of liability (n.) – an oil and gas company is presumed to be responsible for any water contamination within 2,500 feet of an oil or gas well if the water becomes polluted within 12 months of drilling, fracking, or any other oil or gas activity (See § 3218. Protection of water supplies, ACT 13). However, the Department uses a loophole in this law to avoid obvious impacts to water supplies in some cases.

6. Oil and gas operator reports residential water contamination, left to handle its own investigation. The company tells DEP it has tested a homeowner’s water and found postdrill contamination. DEP contacts the water well owner, who declines DEP’s assistance, so the case is left off the books. The company is left to handle the contamination case on its own, without it being registered on DEP’s list of positive determination records.

E.G. 283479 (Wyalusing Twp., Bradford Co.) – combustible gas detected in water supply as part of stray gas problems in the area. Chesapeake Energy handles the investigation; no DEP determination made.

E.G. 287447 (Delmar Twp., Tioga Co.) – elevated methane detected by Shell in water supply; no DEP determination.

E.G. 287444 (Delmar Twp., Tioga Co.) – DEP doesn’t issue a determination letter in this case even though the waterway, not used currently used for drinking, has observable impacts of methane from non-detect in predrill to 21mg/L postdrill. Complaint is also located to the Nestor well which DEP used in a previous complaint to claim background conditions of methane in the predrill even though this complaint does not reflect those conditions.

E.G. 287704 (Leroy Twp., Bradford Co.) – methane problems detected in water supply; Chesapeake handles the case off the books.

E.G. 281744 (Delmar Twp., Tioga Co.) – DEP documents water contamination related to pipeline boring activities resulted in replacement of water supply, yet no determination letter issued “since this water supply was affected by pipeline activites.”

7. DEP water tests find contamination, but fails to make a determination, in some cases for years, until water quality returns to ‘normal’ background conditions. DEP issues a non-impact determination letter and the case is kept off the books. (In other cases, only one predrill and postdrill test is used to conclude whether there’s been water changes.)

E.G. 274235 (Delmar Twp., Tioga Co.) – DEP documents elevated, thermogenic (deep) methane and other contaminants linked to fracking in complainant’s water supply. Sampling continues several times over eight months, and when results are nearer background conditions, DEP issues “non-impact” determination.

E.G. These following examples aren’t necessarily “cooked” but DEP did fail to produce a determination letter according to the files provided: 292895, 291801, 294024, 288672 (Wyalusing Twp., Bradford Co.)

8. The Department or operator cites preexisting or background conditions as reasons for contamination without providing evidence, i.e. predrill test results, to demonstrate a history of water quality problems – or cites no evidence at all. In these cases, contaminants could be considered naturally occurring, but sudden increases typically associated with underground disturbance related to drilling and fracking are written off as normal or are unexplained.

E.G. 267559 (Leroy Twp., Bradford Co.) – DEP finds discrepancy in Chesapeake Energy’s water sampling results, documents methane levels of concern, cites several water tests but fails to provide or cite predrill. Isotopic testing conducted but not included in notes or determination letter.

E.G. 282617 (Leroy Twp., Bradford Co.) – original complaint not included in file. DEP gives no explanation for appearance of methane in water supply, nor does the agency reference predrill or background conditions. Oddly, Department states that it is “continuing to work to permanently resolve this issue” but issues a “non-impact” determination.

E.G. 284102 (Leroy Twp., Bradford Co.) – methane levels attributed to background conditions but no evidence of background provided. DEP finds barium, chlorides, manganese and TDS (all associated with oil and gas contamination) above maximum contaminant levels, provides no explanation about where these contaminants came from, issues “non-impact.”

E.G. 280569 (Wyalusing Twp., Bradford Co.) – predrill tests cited but not provided. Based on complainant’s recollection, however, methane was elevated beyond predrill results. Other water wells report complaints in area; DEP issues “non-impact.”

9. DEP Retention Policy for complaint records says complaints are to be kept on file for five years, “then shred.” [Read the complete front-page cover story about shredding published by ERIE READER on Wednesday, September 16th.]

Around month twenty-eight of this investigation, sitting down to scan the last remaining complaint files, a paper with everything blacked out except one paragraph was left on Public Herald’s file review desk by a veteran PA Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) employee. It read “DEP retention policy.” In a paragraph about “Complaints,” the document revealed that the Department should only hold complaint records for five years after resolution – “then shred.”

Initially, Public Herald figured these records would be kept on microfiche or a digital PDF and that shredding them would only ensure space within the records office. But, after careful questioning with an employee who’s been with the agency for decades, the staff person revealed that only those records which could be considered “useful” would be kept on record at all, turned into microfilm, and “useful” meant only those listed in DEP’s 260 positive determinations. What shocked us even more is that, according to this whistleblower, there is no review committee in place to sift through the “non-impact” complaint records before they are shredded.

To believe that a complaint can’t be cooked is to accept that DEP’s decisions are infallible. But, the question Public Herald had to deal with after seeing so many problems was, “Has DEP ever changed their determination about a complaint?”

In analyzing dozens of “cooked” water contamination determinations made by DEP, Public Herald is only aware of one instance where DEP changed its determination to hold an oil and gas company responsible for pollution after previously letting the company off the hook. In this rare instance, DEP was pushed to reevaluate its decision by an attorney who used the Department’s previous investigations to point out an obvious incongruity.

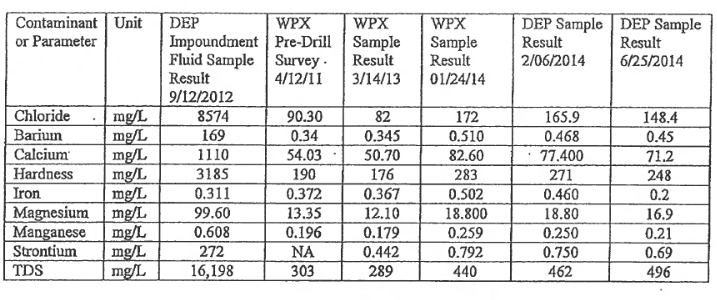

In Westmoreland County, WPX, a Delaware limited liability company drilling and fracking in Pennsylvania, had a leaking waste impoundment that documented complaints show contaminated nearby residential drinking water supplies. DEP tested the water of neighboring homes after the initial complaint was made on September 4, 2012 and later determined two water wells were contaminated by WPX’s operations. DEP concluded pre-drill and post-drill test results showed an increase in chlorides, manganese, total dissolved solids, and other constituents.

But nearly a year later, after a third resident filed a formal complaint about bad water, DEP sent them a letter stating their investigation was “inconclusive,” even though the water had elevated contaminants of the same oil and gas-related pollutants found in the previous two neighboring water wells.

That’s when Nick Kennedy, Esq., a Community Advocate with Mountain Watershed Association, stepped in with a letter “requesting that the Department reexamine the existing data and issue a positive determination letter with all possible haste,” citing a comparison between the third resident’s water and that of the neighbors:

“…the water test results of the ____s and their next door neighbors the _____s….demonstrates that the two neighbors suffered the exact same impacts from the leaking impoundment of the Kalp #1-9H site in Donegal Township. Despite that connection, the ____s received a positive determination, whereas the ______s did not…and examination of the _____s test results shows, as the chart below reflects, that their water exhibited increases in the exact same contaminents…” [author’s emphasis]

After Kennedy’s request, DEP retested the third resident’s water and about one month later, even though the final test was less contaminated than the first, DEP changed their decision. On July 24, 2014, the Department issued a positive determination letter, this time concluding that the third resident’s water supply was also damaged by oil and gas operations.

“Through further investigation and sample collection, the Department has determined that nearby oil and gas operations are responsible for these impacts to your water supply,” state DEP in its letter. The conclusion was made by comparing pre-drill and post-drill test on the water supply, a conclusion the DEP failed to make the first time despite having similar evidence.

Failing to use pre-drill data to accurately make a determination has been a regular practice at DEP. Of many cases uncovered by Public Herald, only the one in Donegal Township did DEP correct itself.

The Missing Complaints

Rewind to Bradford County, in 2012, where Leroy Township was the site of major problems when the Morse 5H well casing failed as Public Herald previously reported in the first part of this series, and showed shocking footage of in Triple Divide where a creek bed turned to a Jello-like surface.

Four positive determination letters have been sent by DEP to complainants roughly half a mile away from the Morse well pad since that time. A total of five complainants were found on file within the township, each relating problems with their water to the Morse well.

These cases are filed as the “Rockwell Run Road Gas Migration Investigation (GMI)” and recently resulted in DEP issuing $193,135 in fines total for the pollution: an average cost of $48,284 per contaminated drinking water supply.

In 2014, Public Herald canvassed Leroy Township to learn more about water contamination from the Rockwell Run GMI and found at least five additional households with water problems in the area that were not included in the complaint records. This means that at least 50% of the complaint data connected to the plume of pollution from the Morse well pad is off the books.

Even though companies are required by law to alert DEP when residents complain to them about water contamination, Public Herald has not found in the records where DEP has held a company accountable for not contacting the Department about a complaint.

Complaint #282623 in neighboring Wyalusing Twp. is one such case, where Chesapeake Energy received a resident complaint, performed independent testing, but never notified the Department of the company’s investigation. Only after the resident became dissatisfied with the company’s handling of the case was the DEP made aware by the resident himself.

THE DEFEATIST CULTURE

Not all citizens choose to report their water problems with the state. And therefore not all complaint pollution is a matter of public record. Instead, some families prefer to work things out only with industry, leaving public data mostly empty about these impacts.

The reason complainants deal with industry and not DEP vary from political taboo — “government can’t be trusted” — to timidness — ”I don’t want to stir the water” — to fear of industry retaliations and financial loss — ”they threatened to turn off my well if I complained.”

“If you want my opinion, the DEP, I do not trust them,” complainant #274235 of Delmar Twp. told Public Herald. “I think someone was paying them off. They tried changing their story. They said they would bring me spring water, and then they brought me two gallons and that’s all I’ve seen of it.” Complainant #274235 was the very first complaint in Delmar Twp. and is also considered to be cooked by Public Herald (please see number 1 above).

Complaint #274235 talks with Public Herald about what’s happened to his drinking water supply. © Kyle Pattison for Public Herald

“We buy 20 to 25 gallon jugs at a time. And we buy three cases of bottled drinking water. If you want to peel potatoes and rinse them, you can’t rinse them with our water…My back room is stacked full of jugs.” Five years later, complainant #274235 is still living on bottled water. DEP took 16 months to make its determination.

Between 2011 and 2013, DEP received 15 complaints from residents in Cogan House Township, Lycoming County. In six out of those 15, the complainant chose not to involve DEP and instead work directly with the oil and gas company.

For Cogan House, most complaints were called in by the operator. However, if DEP obtains evidence from an operator handling the complaint that the operator has potentially impacted a drinking water supply, the Department told Public Herald they’re not legally obligated to step in, investigate and issue a determination.

Ronald A. Schwartz, Assistant Regional Director at DEP’s Southwest Regional Office, when questioned by Public Herald about this issue and how this law of complaint notification is interpreted sent the following answer:

“In accordance with 25 Pa. Code Section 78.51(b) and (c), a determination letter is only required to be made when requests [complaints] are made directly to the Department by the landowner, water purveyor or affected person. However, when we do receive a notice from an operator that they have received notice from a landowner, water purveyor or affected person, field staff call the affected person to see if they would like to make an official complaint/request with DEP. If the affected person wants DEP to investigate then we enter a complaint into the Complaint Tracking System and a determination letter would be sent in response to DEP’s investigation.”

In one case, Anadarko Energy received a resident complaint about water problems, conducted its own testing, and sent water test results to DEP showing methane at 51mg/L, almost twice the explosive level (28mg/L) for a home. Yet DEP backed off the complaint and allowed industry to handle it internally — no further water tests or conclusions were found within the complaint file.

These cases in Cogan House lead to a dead end in public data, where no water tests, determination letters or other records exist to prove that water contamination was not related to nearby drilling or fracking.

STUDIES, STUDIES EVERYWHERE…BUT NO ACCOUNTABILITY

The Pennsylvania Auditor General’s office found flaws with how DEP operates during a 2009 – 2012 Special Performance Audit of Department practices. However damning the AG’s conclusions, nothing seems to have been done to address the problems identified. Since 2011, Public Herald has been looking at cumulative records of complaint cases across the state, hoping that once officials have the data they need, they’ll act to fix regulatory practices that, at this point, are so obviously inadequate and point to systemic failures at the Department.

Despite the importance that complaint records hold in answering the question about total water contamination, recent studies released by both EPA or USGS failed to include an aggregate of complaint data in their conclusions about fracking and groundwater contamination. (Read Public Herald editorial: “EPA Missed Thousands of Water Complaint After Telling Public Fracking is Safe“)

When cumulative complaints are considered, the question facing communities becomes, “How much of a percentage of water contamination will your township allow from fracking?”

Public Herald has made months of requests to share data and interview Governor Tom Wolf about these major flaws in the regulation of oil and gas development in Pennsylvania. However, none of our requests have been answered. Meanwhile, in 2015, Wolf’s DEP has issued 1,471 additional unconventional fracking permits and the number of positively determined contaminated water supplies has continued to increase since Wolf took office.

At a time when drinking water is becoming more scarce, this complaint investigation helps tell the story of how parts of America’s drinking water supply is being damaged by both state and industry officials.

The Pepper Appeal

Christine Pepper made a call to DEP a month before she opened that determination letter to explain her face stung and burned after splashing water on it like she’d done a thousand times before. When Public Herald visited her home about a week after the DEP investigation began, she had rows of empty plastic water jugs running along the floor and a large water buffalo hooked to a trailer in the driveway.

The DEP determination letter is generally the end of the road for an investigation. And if you’ve been listed as “non-impact” there’s no turnaround other than to appeal DEP’s decision. But in all of our research, Public Herald has never come across a complaint investigation that included an appeal by a resident.

Then on November 17, 2014, Christine Pepper did the unthinkable and filed an appeal to challenge DEP’s determination.

Stay tuned for the next installment from INVISIBLE HAND and read more about what Public Herald uncovered and Christine Pepper’s fight to save her drinking water. This is the second installment of Public Herald’s Complaint Investigation as part of the INVISIBLE HAND series.

This article is dedicated to the memory of the late Pennsylvania attorney Bob Ging, a.k.a. “The Good Lawyer”, who recently left this world, through his selfless actions, better than he found it. 1950-2015

CONTRIBUTORS

File Team members from #fileroom who scanned/organized/published complaint records: John Nicholson, Aziz Lalani, Ducky, Casey R. Pegg, Zora Acephala, Kyle Pattison, Amanda Gillooly, Joshua B. Pribanic, Melissa Troutman

Multiple photographs used in the making of this report were taken by Steven Rubin & Kyle Pattison for Public Herald

Public Herald is nonprofit, fearless investigative journalism. Our independence is guaranteed. We’re publicly funded, which means we work for and are supported by public donations. Our Members have carried us here. Join us.

I know first hand about DEP. We live in Gasland. DEP told me they would not drink my household water after the latest test. We continue to buy bottled water-6 years now. Another woman, elderly, widow was told by DEP to get a lawyer since her water cannot be “fixed” by the gas company. She has been supplied water for 4 years now. The gas company will buy her out but for a ridiculous amount of money. Her loss for being part of the necessary sacrifice. DEP serves one God-Gas.

Wonderful job of shining the light on a collapse of good government.

Same thing happened to us in Jefferson County. Water fine till Marcellus well was drilled. DEP issued a non-impact determination letter

Thanks for sharing. If you’d like to email your complaint # docs check out publicfiles.org. Public Herald plans to release the files for Jefferson in 2016 and any additional info would be helpful.

BIG CHEERS! Wonderful investigative journalism!

So, there has to be some guidance or leadership on obfuscating the complaints. Who or what? Have you been able to determine that? Certainly we know that the State administration was very oil-gas friendly. Wasn’t the leader of DEP then Michael Krancer (sp?)

From our spreadsheets and experience on these files it appears the secretary is not directly involved in the decisions of the complaints. There is always an “inspector” and “supervisor” on each complaint. Most often, as in the Delmar Twp. cases, the same inspector is responsible for all the complaint investigations in that township, with mostly the same supervisors assigned to them. From here, we’ll be requesting the email records so long as we have enough financial support from the public to push through with the RTK.

Joshua & Melissa: I saw “Triple Divide” about a year ago. Keep up the great work. I shared a link to this article here: http://gomarcellusshale.com/forum/topics/database-of-complaints-to-dep , so that people closely following the industry (leaseholders and gas workers) would be more likely to see it.

Thanks Paul. I’m attaching an image hear to give you a better sense of the total numbers for your audience as I see your getting some heat that most of these complaints are about dust in the air or something innocuous. In fact, as you can see from the numbers, the majority of the complaints are with water contamination from fracking (1275 investigations). Also, a number of general complaints also deal with water quality issues and are sometimes filed in the wrong category or deal with stream impacts. Might also be helpful to share these numbers for the 17 counties. Best,

Struggling with significant health issues from hydrofracking and received no-impact determination letter in July. I was denied further VOC testing, as well as access to any available true “pre-drill”(08-09) water testing reports in Granville Summit due to “confidentiality issues”. I went to Casey’s office and filed a Congressional Inquiry, and now the DEP agrees to the additional testing. I’m not optimistic that I will get the results to pinpoint exactly what chemical (s) is causing these terrible health issues. A question: are you aware of any way to get access to actual pre-drill reports (DEP does not deny they exist, they just will not provide them)? Also as we look to purchase a new home we can’t help but notice very specific areas in Bradford County that have significant amount of homes for sale that are in the same areas as recent groundwater contamination violations. This is all happening very quietly.

Thanks for sharing and we’re interested in learning more about your story. If you’re able, please contact [email protected] and we may be able to help in finding and discussing the baseline for Granville.