Pennsylvania is Discharging Radioactive Fracking Waste Into Rivers As Landfill Leachate, Impacting The Chesapeake Bay & Ohio River Watersheds

Joey Bacon (left) fishes the West Branch of the Susquehanna River in Williamsport, Pa. with his friend. © Joshua B. Pribanic for Public Herald

Pennsylvania is Discharging Radioactive Fracking Waste Into Rivers As Landfill Leachate, Impacting The Chesapeake Bay & Ohio River Watersheds

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

SUPPORT newsCOUP

Public Herald is a nonprofit newsroom that holds those in power accountable.

You can receive our latest breaking stories by subscribing to our newsletter

or becoming a Public Herald Patron.

by Joshua B. Pribanic and Talia Wiener for Public Herald edited by Melissa Troutman

August 7, 2019 | Project: Smoking Gun | Podcast: newsCOUP

Joey Bacon, 13, stands ready under the Lance Corporal Abram Howard Memorial bridge in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, with his fishing pole cast into the West Branch of the Susquehanna River. Joey spends a lot of time around the Rivers swimming, fishing, and cannon-balling from the bridges that crisscross the waters. He hasn’t caught anything in the hour he’s been out today, but one time he caught a catfish as long as his arm, and he’s hoping that will happen again.

Water that travels ninety-one miles downstream from Joey ends up at the Pennsylvania Governor’s Residence on the Susquehanna River in Harrisburg. On any given day, Governor Tom Wolf could look out from his window to wildlife on the River and people recreating in the waters rushing by.

But what Wolf can’t see, is that his own Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has allowed radioactive material from fracking waste to be discharged into that River through sewage facilities upstream.

A Public Herald investigation has uncovered that DEP is allowing 14 Sewage Waste Treatment Plants to discharge radioactive fracking waste as landfill leachate into 13 Pennsylvania waterways. The process DEP created to “treat” and discharge the leachate through sewage plants appears to date as far back as the fracking boom (2009 or longer).

The size of this story is vast and the numbers are overwhelming. The 14 discharge points hit waterways across the Commonwealth.

In the east, the effluent of pollution flows from three facilities upstream of Harrisburg down the Susquehanna River into Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay.

In the west 11 facilities — one hitting the Allegheny River from a plant in Johnstown, another reaching the treasured Youghiogheny River — are discharging radioactive fracking waste as landfill leachate into the Ohio River watershed.

At start of 2019, there were 15, not 14, sewage facilities overseen by DEP to send landfill leachate to waterways. But one facility, the Belle Vernon sewage plant in Fayette County, shut down its leachate intake in May after superintendent Guy Kruppa said it was “killing their bugs.”

When we asked the Department to provide the total annual volume of leachate for each of the 15 facilities, the DEP told Public Herald, “We do not have this information available.”

Dissatisfied with this response, we’ve requested that the Department find out why and how they could not know the amounts. An official response is pending.

Our own review of sewage discharge data from the Belle Vernon Plant says the total amount of landfill leachate potentially released to these 15 facilities, on the low end, is 547,500,000 million gallons per year (36,500,000 million gallons annually per facility), depending on rainfall. On the high end we’re looking at 1.6 billion gallons of leachate per year.

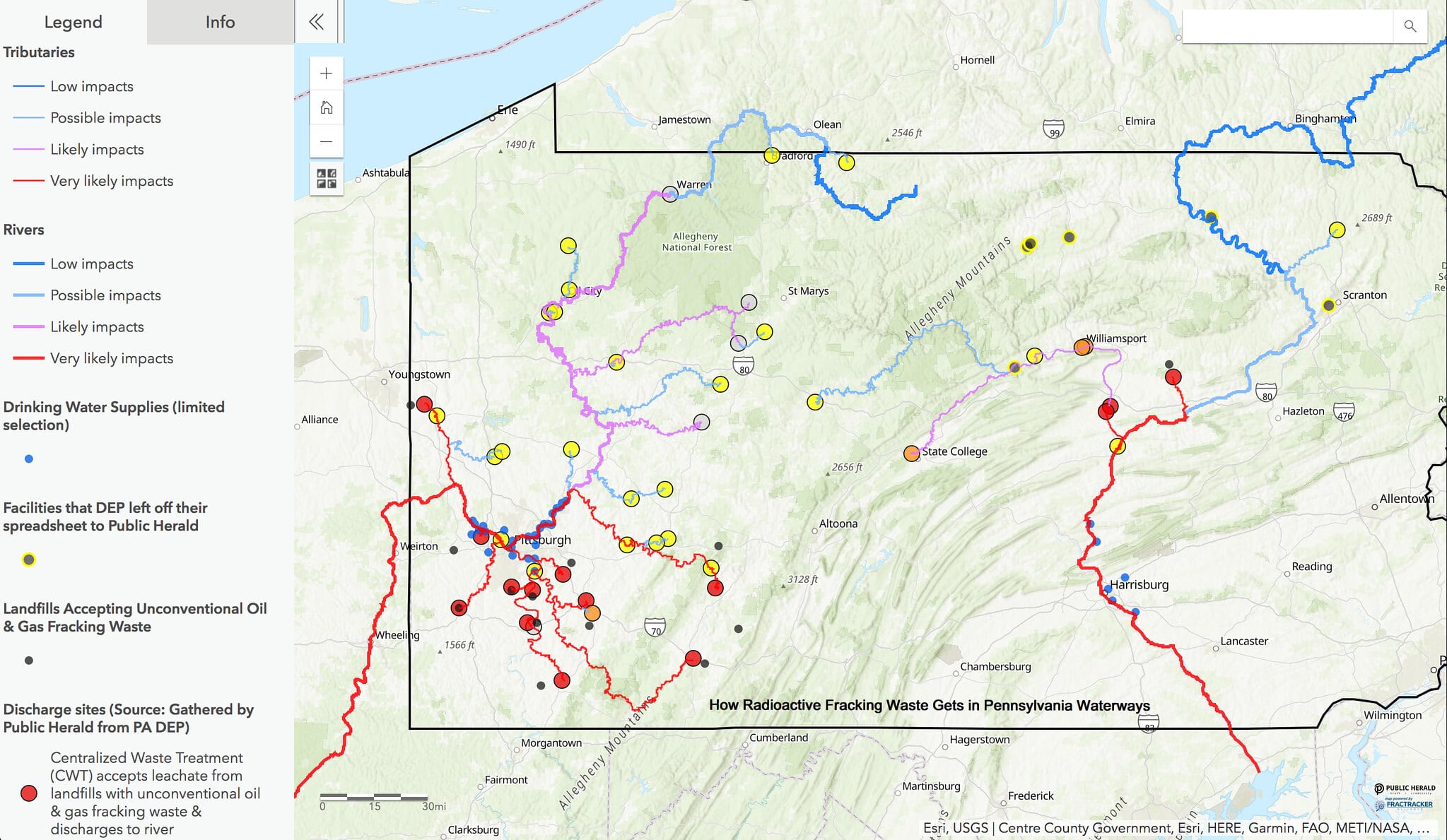

Where and how this is all happening is best illustrated in the Public Herald interactive map “How Radioactive Fracking Waste Gets Into Pennsylvania Waterways” — produced with FracTracker Alliance.

Click on the map to view the details. Data was gathered by Public Herald from questions to the PA DEP. Public Herald had to correct DEP on a number of errors in their answers.*

In addition to the sewage authorities, the map is a guide for treatment sites that currently or previously received fracking waste (orange dots), and discharged to a sewage plant or straight into a creek. It includes a limited selection of drinking water supplies located downstream of 14 facilities (blue dots), and the potential areas of pollution from sewage plants who receive some form of fossil fuel waste (yellow dots).

How Does Rain Turn Into Radioactive Leachate? And How Much is Out There?

© Steven Rubin for Public Herald

When rain falls on a landfill in Pennsylvania, water passes through the collected waste and leaches out some of the soluble constituents. That liquid is contained and stored as leachate.

The landfills** who accept unconventional drilling solids, a.k.a. fracking waste, are receiving wastes that contain high levels of Technically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (TENORM), mainly in the form of the radionuclides radium-226 and radium-228.

According to a recent study 80% of Pennsylvania’s drilling waste stays in the state. An average of 800,000 tons of fracking waste a year is indicated to be sent to landfills in Pennsylvania based on industry data reported to DEP for 2019.***

TENORM can be in the waste stream of pipe scale, produced waters or flowback water, sludge, used water filtration sleeves (radioactive socks), and contaminated equipment.

Those radionuclides in the waste are water soluble. So when it rains, they pass into the leachate and make it radioactive.

That’s a major problem according to Dr. Avner Vengosh of Duke University who’s published extensive research on the cradle-to-grave life cycle of fracking waste radionuclides.

Vengosh told Public Herald that a sewage authority is not capable of treating radioactive material in fracking waste and inevitably would discharge radionuclides into the water.

“In leachate [from fracking waste], I would expect to see salts, metals, and radioactive elements,” said Vengosh. “None of those would be retained or removed through conventional wastewater treatment plants.”

In a 2018 article Vengosh said that in these cases “even if only a small amount of radioactive material remains in the outfall, and the volume of effluent is large, one can expect to see a build-up of radiation in river sediment.”

Guy Kruppa [that sewage authority superintendent who led the charge at Belle Vernon] provided Public Herald with his independent test results that detected 8 pCi/L (Picocuries per liter) of radium (Ra) 226 and 228 in one sample of their discharge. The leachate straight from the landfill tested at 50 pCi/L. The maximum contaminant level (MCL) for radium in drinking water is 5 pCi/L.

Kruppa says their one-time sample of radium is without a doubt on the low end. The reduced radium in the discharge is not necessarily a reduction of radium but rather a dilution.

If you convert Liters to Gallons (3.785 L/gal) — 8 pCi/L would be 30.28 pCi/gal. If the total discharge from the 15 sewage plants is 575,500,000 million gallons annually then the potential Ra (226 and 228) would be 17,426,140,000 pCi/gal — or 17.4 mCi (millicuries).

The results indicate billions of gallons of untested, unregulated radionuclides discharged each year to waters of the Commonwealth under the supervision of the EPA and DEP.****

“Once the effluent is being disposed into the river, the radioactive element will sink or absorb into sediment at the bottom of the river at the disposal site and start to accumulate there,” Vengosh said. His own studies in Pennsylvania found high concentrations of radionuclides in river sediment.

Not only would radium in leachate get into the water untreated in these instances, it would also “kill the bugs” at the sewage treatment plant and force the discharge to release additional contamination to the waterway.

“Once again, waste from the fracking industry is winding up in our drinking water,” Dr. John Stolz, the Director of Duquesne University’s Center for Environmental Research and Education, said to Public Herald.

“Sanitary landfills are no place for drilling wastes that contain toxic metals, organics, and radioactive materials. The leachate from these landfills is so toxic it kills the microbes whose job it is to treat it. The amount of total dissolved solids in the discharge water I tested at Belle Vernon was almost three times the legal limit. There were high levels of bromide — (and the landfill knew I was coming so the discharge flow had been shut off suggesting my readings would have been much higher) — all of which impacted the Charleroi drinking water plant downstream.”

The Guy Kruppa Story

“We were the landfill’s permit to pollute.”

© Steven Rubin for Public Herald

“We noticed in 2015, 2016, 2017 that the Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill constituents were starting to indicate that they were accepting fracking waste,” Belle Vernon Sewage Waste Authority Superintendent Guy Kruppa told Public Herald in this extensive interview.

LISTEN TO GUY’S FULL INTERVIEW

“The indicators were things as sodium, calcium, chloride, barium, high conductivity, TDS — so those were what we were looking for. It wasn’t until we were hot on the trail that it was confirmed by a subcontractor at the landfill that they were taking fracking waste: things laced in diesel fuel, cake, things used in flowback and things used in drill cuttings.

“We contacted the DEP and told them that we think they are taking frack waste.

“And I told them this thinking I was going to tell them something they didn’t know. And the DEP guy said, ‘yeah, we know.’

“I said ‘you know the landfill is taking frack waste?’ And DEP said, ‘yeah, they’re only allowed to take so much.’ I said do you know how much they’re taking? And DEP said, ‘yeah, they record it on our system.’

“I said do you know they’re taking it at night and on weekends when the landfill is closed. And DEP said, ‘well they’re not allowed.’

“And I said, ‘It might not be allowed, but they’re doing it.’ And DEP said, ‘Well, I don’t know what to tell you.’ And I said, ‘I know what to tell you, they’re taking it!’

“DEP said, ‘it’s on an honesty policy and they’re supposed to report it.’ I told them they’re taking it under the cloak of darkness, long before the landfill opens.

“Those constituents that are in that leachate aren’t in municipal sewage. We had to have special tests done by our lab to figure it out. Then we started to find out more about frack waste, and we said we needed to test for radiologicals. So we got West Virginia University to do an independent study on the effluent of the leachate and our effluent at the sewage plant.

“The thing about Pennsylvania is there’s really no limit to what we can discharge because let’s face it, that stuff shouldn’t be in there. Sewage plants aren’t usually regulated for something like that.

“But, we have to follow drinking water standards which is 5pCi/L for radium and we found out through the independent study we were discharging 8pCi/L. So, we had to notify users such as the Charleroi Drinking Water Authority a mile downstream.

“When I told this to the DEP inspector he said, ‘Well what side of the river are they on?’ And I said, ‘They’re on the opposite side about a mile.’ So he says to me, ‘Oh, well they’re good, they’re on the other side.’

“The funny thing is a guy from Charleroi drinking water calls me up three days after we turned off the pipe. He says, ‘Did you get the landfill shut off?’ I said, ‘Yeah. Why, did you hear?’ He says, ‘No. We haven’t run our caustic pumps in ten years, and we had to turn them on.

“To me, that’s scary. Their PH was down, but for the last ten years it’s never been down. So, is that all coincidental…does our water not reach the other side of the river?

“With the DEP, if they don’t test for it, it doesn’t exist. It’s not there.

“You might as well say this stuff is hazardous waste. It was industrial waste.

“We were the landfill’s permit to pollute. We weren’t required to analyze for these [fracking contaminants] so it was passed right through the plant to the Monongahela River.

“These animals that are in these tanks breathe air, so if you feed them a steady dose of salt, which was high in chloride, they’re not going to survive. So the landfill leachate was killing off our bugs, therefore we weren’t able to treat sewage very effectively.

“And I was reporting these violations that we had to the DEP. So they were well aware that we weren’t making our limits.

“So the major danger was we were passing these things through to the source water.

“At first the landfill was very cooperative and said they would do all they could to solve the problems. And they did nothing.

“They had some smart PR spokesperson who came out and said they never had any violations. Well that’s true, they don’t, because they don’t have those limits.

“They don’t have [our] NPDES permit. We do. So they can discharge pretty much anything they wanted and they weren’t going to violate anything.

“The DEP is so compartmentalized that we answer to Clean Water and the landfill answers to Solid Waste. We were telling our problems to Clean Water, but they weren’t relaying our problems to Solid Waste. For Solid Waste, you might as well say they are a waste, because they were not conveying our problems to Clean Water.

“You have a giant loophole in the DEP. You have Waste Management on one side and you have Clean Water on the other. And running right through the middle is pretty much their leachate. It’s unregulated and no pretreatment was required.

“But the DEP didn’t go to them and say they had to do something about it.

“I have lost a lot of respect for that institution [for the DEP]. We rely on this state agency to protect our source water, to protect our resources, to protect our environment. And this is their solution?

“It’s a complex situation. You rely on the DEP to help you, and they didn’t give us much help at all. We had to do it all on our own, which is pretty sad.”

A “Giant Loophole”

© Steven Rubin for Public Herald

In some states and U.S. territories, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issues National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits, which set limits on the discharge, monitoring, and reporting of pollutants. But in Pennsylvania, the EPA has mostly delegated that power to the PA DEP.

In order for a landfill to create and ship leachate, the EPA does require its own NPDES permit. But once the leachate leaves the landfill and is trucked to the sewage authority, a new NPDES permit is approved by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. This permit doesn’t identify the leachate as a component of fracking waste and there’s no requirement to test for those contaminants.

This switch from fracking waste, to landfill, to leachate, takes the liquid out of the DEP’s office of oil and gas and places it inside the solid waste management department.

In a statement to Public Herald on July 17, Roy Seneca of EPA Region 3 said it evaluates the PA DEP’s implementation of NPDES permits in various ways, including but not limited to “review of select draft permits developed by PADEP, Permit Quality Reviews which are performed on a 5-year cycle, Issue Resolution Calls to discuss solutions to ongoing issues, and conducting annual state meetings.”

And there have been cases when the EPA has stepped in due to a failure by the DEP to follow proper procedure. In 2011, the EPA had to tell the DEP to stop sending fracking wastewater shipments to sewage authorities after elevated bromide levels caused trihalomethanes to spike in drinking water facilities downstream of the sewage plant discharge.

So now they only send leachate. That’s the loophole.

DEP’s Community Relations Coordinator Lauren Farley told Public Herald they have no evidence that high ammonia concentrations or leachate from the Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill has caused “killing of the bugs” that support Belle Vernon’s sewage treatment. And no issues were found with the Monongahela River.

DEP said they have conducted multiple inspections at the facilities and found that they were in compliance with permit and state regulations. [Public Herald has no evidence that DEP performed a single test to qualify this statement.]

That was backed up by Deputy Secretary for the Office of Oil and Gas Management Scott Perry who reassured community members in a private meeting June 11 with municipal leaders and industry that DEP had the Belle Vernon situation under control.

“In Pennsylvania, we have a history of using sewage treatment plants to treat oil and gas wastewater,” Perry said. “We acted swiftly [in the past] to basically eliminate the ability of shale operators to take their waste water to facilities that can’t properly treat it.”

Kruppa says DEP’s story is wrong. Kruppa was hired to the sewage plant in March 2018. He said the guy he replaced told him to take this landfill thing head on, and that’s when he started to find problems right away in the system.

Kruppa told Public Herald that DEP tried to make a deal. They told him the Department would hold off on any violations to the sewage plant so long as they continued to accept the leachate. And Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill would pay a regular fine for sending it.

DEP’s story says when they found “no evidence or significant impact to the river,” they asked Guy Kruppa to continue accepting the leachate from the landfill. Kruppa says, “The radium 226 and 228 was above drinking water standards and being discharged. How’s that okay? I told them we couldn’t treat effectively because we had bugs die off.

“If you weren’t talking to Howard Dunn, the DEP inspector, or getting a statement from Howard Dunn, then that tells you how ineffective their communication is. I told Dunn, he came and did an inspection. He knew of it and they also knew of the radium levels. I told them we are non-compliant in a hard copy, and couldn’t satisfy the NPDES requirements.”

In a final disturbing statement from Kruppa, he says he mistakenly told the landfill when they tested for their NPDES permit, so the landfill would shut off their leachate pipe for a few days until after the test was completed. He said this kept them within their permit requirements during the test, but afterward the system was back on and the leachate problems continued.

Once Fayette County District Attorney Rich Bower and Washington County District Attorney Vittone got a hold of the case they had enough of DEP. They petitioned the Fayette County Court of Common Pleas for a 90-day injunction to prevent the landfill from continuing to deliver leachate to the sewage treatment plant. The injunction was issued on May 17 and has now been extended to one year.

The leachate from the Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill is now trucked to treatment facilities in Ohio — something DEP tried to avoid.

“We communicated to Belle Vernon that we preferred they continue to accept the leachate in the interim as opposed to Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill trucking it to another facility,” said the DEP in a statement to Public Herald. “Trucking the untreated leachate from the landfill to other facilities brings its own risks to the environment.”

But the story doesn’t end there. The Pennsylvania Office of the Attorney General (AG) has now taken over the Belle Vernon case.

Public Herald learned that Kruppa and an operator at the plant have recently spoken with two agents from the AG who mainly wanted to know about DEP.

Kruppa’s recounting of the 2.5 hour interview confirmed what Public Herald has been told by sources following our 2017 report on oil and gas complaint investigations, that the DEP is being investigated by the AG.

Our own expert source Dr. John Stolz, who worked with Public Herald closely on reviewing DEP’s conduct for reports, was grand juried by the AG in June. He says the DEP was shown “no mercy.”

PA Attorney General Josh Shapiro’s office denied a Public Herald Right-to-Know request for files dating back to 2017 on fracking investigations. Their office would not comment on whether the Department is implicated in ongoing investigations.

The Governor’s Watch

© Joshua B. Pribanic for Public Herald

Back on the West Branch of the Susquehanna River, Joey Bacon is still perched on the bank, fishing pole cast far into the water. 100 feet to his left, a discharge from the Williamsport Sewage Authority is pumping out effluent at a rate of hundreds of thousands of gallons a day. Some of that effluent comes from Eureka Resources, who treats fracking wastewater, and none of the effluent is tested for radionuclides at either facility.

Like Joey, thousands of kids spend their free time around these leachate-laden rivers fishing, swimming and playing around with friends. The expectation is Governor Tom Wolf’s DEP is keeping those rivers safe to swim.

But no one, not the DEP, not the EPA, not the watchdog groups, are testing the rivers for radiation.

“Even dedicated brine treatment plants aren’t doing enough to deal with the radiation problem,” Dr. Stolz explains. “On a recent tour of the Williamsport facility, our group was told they test for radiation using a hand held gamma detector held six inches from the truck. That’s not going to protect the public.”

The DEP relies on systems like the one Stolz mentions to test gamma on the outside of trucks, but Radium 226 and 228 are alpha, they release beta materials that don’t pass through metal. In these cases, holding a device next to a metal truck is not going to tell you if it’s “hot.”

“You have raw sewage and radioactivity spewing into the river,” said Justin Nobel who’s written extensively on this topic for Rolling Stone. “In a well run state that cares about their people and values health and science, they would immediately test every single community on a river or creek or waterway where there’s a treatment plant or a discharge point of potential oil and gas radioactivity. That should happen right away, and I don’t think that has happened.”

“It’s shocking to think about the millions of people who have potentially come into contact with contaminated water,” Youghiogheny Riverkeeper Eric Harder told Public Herald in response to this report. “Many who assume the waterway is safe for recreation.

“The DEP has known that fracking waste contains highly radioactive elements like radium at concentrations more than 1000 times the drinking water standard. Yet, they have failed to properly safeguard the public against the impacts of this toxic wastewater.”

An Earthworks report published on June 18, 2019 written by Melissa Troutman, who is also co-founder and executive director of the Public Herald, found that regulations on oil and gas waste management have not improved in the past few years and in many cases have worsened.

Governor Tom Wolf’s office has declined to comment for this report.

Cancer in the Water

© Joshua B. Pribanic for Public Herald

20 minutes downstream from the East Washington Joint Authority Sewage Treatment Plant, a facility accepting radioactive landfill leachate, sits Canon-McMillan High School. Within the past ten years, students at the high school and the other eight schools in the district have been diagnosed with various cancers at an alarming rate.

Each year, 200-250 children in the United States are diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma, a rare bone cancer. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, six students within the school district were diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma since 2008. Three students have died.

In April 2019, the Pennsylvania Department of Health released a 17-page report stating that there had not been a cancer cluster in Washington county, and that the rates of the sarcoma were not statistically significant. The Post-Gazette since documented “up to 67 childhood, teenage and young adult cancers over the past decade in Washington, Westmoreland, Fayette and Greene counties.”

Knowing the East Washington Joint Authority Sewage Treatment Plant is accepting landfill leachate from fracking waste and discharging to Chartiers Creek near the school puts a new spotlight on the problem.

“Well drilling waste typically contains a number of toxic pollutants such as radium and other radioactive materials, heavy metals, and arsenic. These are known carcinogens that can cause serious and dire health consequences for years to come,” says Raina Rippel, Director, Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project.

“‘Treating’ such waste at a facility that discharges into Chartiers Creek – as the East Washington sewage treatment plant does – could create a public health crisis for residents living nearby and those downstream who come in contact with these contaminants.” Rippel says in response to this report that “To help prevent such a crisis, we call for immediate testing of any discharges the plant makes, as well as frequent monitoring of water quality near the point of discharge and further downstream.”

The Leachate Continues at 14 Facilities

© Joshua B. Pribanic for Public Herald

Though Belle Vernon was the first town to blow the whistle on DEP, Public Herald found other treatment plants in the state have faced similar issues for years, dating back to 2009.

In Westmoreland County, Laurel Highlands, and Brush Creek, DEP has watched ammonia problems develop because of leachate.

In Belle Vernon, only Kruppa and town officials who questioned the state put a stop to DEP’s leachate problem.

Guy Kruppa may have won that fight for now, but the DEP story isn’t over. At a sewage meeting this month he ran into an operator from another facility in Uniontown who’s accepting leachate.

Uniontown heard about what DEP did to Kruppa. So they’re taking a closer look at their own plant.

The landfill facilities DEP provided to Public Herald for this report were incomplete. We uncovered during this investigation that there are other landfills in the state who take on fracking waste and were not mentioned in DEP’s spreadsheet.

Those facilities, like Evergreen Landfill and Northwest Sanitary Landfill, have been cited for leachate violations within the past ten years, but it is unclear where their leachate is going. And this isn’t an exhaustive list, it’s just the ones we saw at the top of the pile in a targeted search.

Wayne Township Landfill in Clinton County, which kicked off this report for Public Herald, also receives unconventional fracking waste from Eureka Resources, but has declined to comment for this story.

It remains unknown where Wayne Township Landfill’s radioactive leachate ends up.

***

![Melissa Troutman Director of Triple Divide Redacted Melissa Troutman Co-Director Of Triple Divide [Redacted]](https://publicherald.org/wp-content/uploads/bfi_thumb/Melissa-Troutman-Director-of-Triple-Divide-Redacted-nnvlh4ducuo1m564it06enejx7j7x1hyrt38u63a1s.jpg)