Correction: DEP’s record office originally informed Public Herald and our sources that only 28 WMGR123 permits were issued for the entire state. But upon further questioning our #fileroom File Team confirmed that this permit file is handled differently than oil and gas records, and is instead treated as a waste record. The waste records are divided into six regions of the state, meaning the 28 permits cited in this report are strictly for the north central region. DEP did not know how many permits have been issued to the other five regions.

by Joshua B. Pribanic & Amanda Gillooly for Public Herald

this story is part 1 of 6 in the INVISIBLE HAND series which covers open meetings and the execution of local and state laws

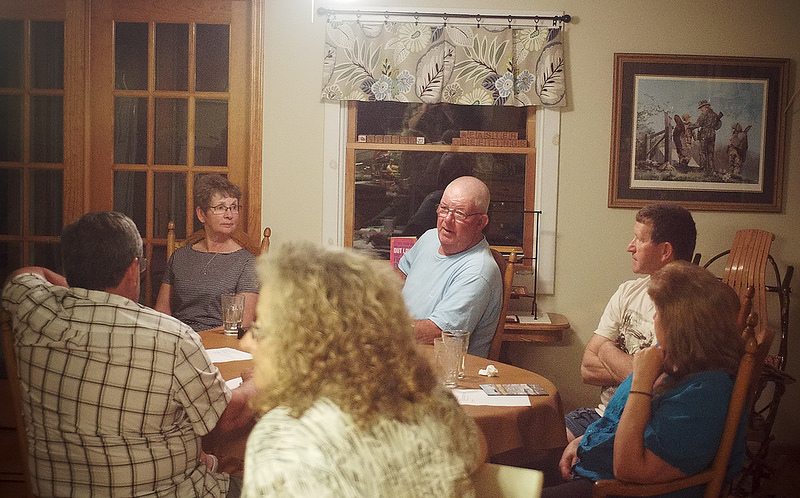

Nine Smithfield Township natural gas leaseholders have banded together to fight a new permit from the state Department of Environmental Protection that allows more than 700,000 gallons of toxic waste to be stored in backyards for years.

Driven with frustration by Chesapeake Energy and DEP’s lack of communication to the township, a nine-member group of residents, represented by spokesman Dick Stedge, formed and filed an appeal to a WMGR123 permit approved in March.

The permit allows Chesapeake Energy to store 756,000 gallons of oil and gas liquid waste in tanks for six years on a tract of land owned by Lamb’s Farm Storage.

The group, accompanied by like-minded residents and two consultants, packed three open meetings over three months (March-May) to voice their concerns, citing 12 objections listed in their appeal.

“The Department of Environmental Protection’s issuance of the permit was an arbitrary, unreasonable, contrary to law and the issuance was made without adequate investigation and disclosure of facts to the people,” Stedge said during a township meeting in May.

A second appeal was also filed by the three-member board of township supervisors after receiving pressure from residents during an April meeting. But supervisors Jacqueline Kingsley and John Allford repeatedly downplayed safety concerns at the May 13th meeting.

Smithfield Township supervisors prepare to hold a meeting in April 2014. From right to left: solicitor Gerard Zellar; supervisors Jackie Kingsley, John Allford, Russel Burkett; and secretary Jennifer Chilson who resigned after this meeting. © Joshua B. Pribanic for Public Herald

“Safety wise, I’m not really concerned about the safety of it. They’re in containment, they’re in closed tanks, the people have radiation monitors on them,” Allford said.

“These fluids are being brought up on every well pad in the area and no one has said a word about these same fluids,” said Kingsley. “Am I concerned about it? Yes, I’m concerned about the whole process. But, why are we singling out this facility?”

“Like it said in the [local] paper, we all did this to ourselves. Not 100 percent of us, but majority of us signed gas leases. We let these people in here and we gotta deal with it,” asserted Allford.

But a grandmother argued, “I’m raising both my grandchildren there and we have a pond right below the site that you people are discussing. Children swim in it.”

The supervisors maintained, “DEP authorized the permit. DEP are the environmental experts. They’re the ones who need to answer your questions.”

“I was never given notice,” the grandmother retorted. “If there’s runoff from the top of the hill, I’m not gonna know anything until they get cancer.”

Carol French speaks as a consultant to a group of residents in Bradford County about Marcellus shale activities. photo: jbpribanic

DEP spokesman Dan Spadoni told Public Herald over the phone, “We will not comment on the permit since it’s under appeal.” Yet, the township supervisors told residents to write down questions and a local government liaison at DEP would try to get them answered.

Calls by Public Herald to Chesapeake Energy were unreturned.

While the DEP classifies the permit as a “Processing and Beneficial Use of Oil and Gas Waste,” the group maintained that it’s a “deceptive” name, adding Chesapeake has not fully disclosed the intended use of the facility.

If the storage area is permitted for six years, said the group, the site will be, in actuality, a “wastewater recycling facility in our backyards.”

Smithfield Township officials were notified of the approved permit in a two-page certified letter in March, yet provided little information to concerned residents in April or May. This prompted residents to question the motive for the supervisors’ appeal.

“It makes a hell of a difference whether you guys are on board or not with us,” said Bruce Kennedy. Residents stressed they appealed the permit to prevent long-term waste storage facilities in backyards, but supervisors said they entered the appeal as a means to “glean more facts.”

That’s when Stedge again stood up clutching a copy of a certified letter from Chesapeake Energy sent to the township in October 2013 informing the supervisors of the permit for the proposed storage facility.

Pressed about why they had not taken action to get facts sooner, the supervisors collectively shrugged their shoulders and said they could not recall receiving the paperwork.

“You guys probably fumbled the ball for the team,” one resident told them. “And I think you need to get the ball back for us.”

“We screwed up — we missed a piece of paper,” said Kingsley. “You want us to undo it? How about we all undo it, and we undo our gas leases. The gas company will go away, our problems will go away, and we will all get along.” Several in the audience applauded.

Kingsley added that the type of permit issued to Chesapeake was “nothing new,” which sparked a renewed debate.

Knapp confirmed that the storage facility indeed was something new, with only four issued in Bradford County and 28 permitted in the north central region, one of six regions in the state.

Bruce Kennedy listens to Carolyn Knapp after the May meeting. photo: jbpribanic

“If you two aren’t going to be supportive, you are wasting taxpayer dollars,” Bruce Kennedy told the supervisors. He beckoned toward solicitor Gerard Zeller, who will be handling the appeal for the township, saying “You may as well tell him to slack off right now.”

Kingsley reassured the residents, “We work for you. We filed the appeal. And we will follow through.”

Fracking Waste

Waste water storage and disposal remains one of the most predominant and controversial issues associated with fracking. In Pennsylvania, as it has become more difficult for companies to treat and dispose of waste, alternate methods are on the rise.

Yellow tanks in the distance hold hundreds of thousands of gallons of fracking fluid waste from nearby Marcellus shale drilling in Smithfield Township. photo: jbpribanic

“Waste from this industry is one of the biggest issues around. They don’t know what to do with it. They don’t know where to put it, and it is highly radioactive,” spoke Knapp at the township meeting.

To reduce off-site disposal at waste injection wells or treatment facilities and use of centralized wastewater impoundments, industry leaders in Pennsylvania are moving to on-site treatment and recycling of waste, an alternative often quoted as being safer for everyone and known more commonly as ‘closed-loop systems’ which the WMGR123 allows.

In March 2012 DEP created the WMGR123 permit, a move that merged three redundant permits into one, “providing clarity for the regulated community, general public and the department.”

In a public notice from DEP, “WMGR123 encourages the reuse of liquid wastes generated on oil and gas well sites and related infrastructure through a closed loop process that allows the return of treated liquid waste to oil and gas well sites for reuse, thereby minimizing water withdrawals and impacts on this Commonwealth’s valuable water resources. Solids generated by the treatment process are residual wastes and must be managed in accordance with the residual waste regulations.”

But on-site treatment is not without problems. Recent DEP file reviews on closed-loop systems by Public Herald found repeated spills, equipment failures and torn protection liners.

Permit files collected by Public Herald show spills, etc. with closed-loop systems. More files available at publicfiles.org. photo: jbpribanic

Permit files collected by Public Herald show spills, etc. with closed-loop systems. More files available at publicfiles.org. photo: jbpribanic

Is Local Zoning The Answer?

“You want us to back peddle and you want us to undo — but it can’t happen. It can’t. And believe me, my husband tried when they moved in up there. He begged them to take the money back. I know. It doesn’t happen.” — Jackie Kingsley

Supervisor Jackie Kingsley sits next to John Allford at a Smithfield Township meeting in May. photo: jbpribanic

One concerned resident advocated for local zoning to give the supervisors power over oil and gas operations, noting that the township had an ordinance to regulate mobile homes but not frack waste trailers.

“What is the difference between a mobile home and a 70-some foot trailer?” the man asked. “I know you said that they’re already there, so we can’t stop them. But why can’t we stop ones in the future? Can we put ordinances in to prevent another one from going in?”

The solicitor responded, “In the state, you can’t just single out a particular industry and regulate it so that it’s ‘not in my backyard.'”

The resident replied, “We’ll, let’s not single out just one.”

“Does Ulster not have an ordinance? It’s my understanding that’s why it’s in East Smithfield instead of Ulster,” another resident said.

Sixty percent of Pennsylvania municipalities have zoning ordinances on the books, giving them an extra layer of protection for residents who live near oil and gas operations.

In Cecil Township of Washington County, a community just south of Pittsburgh, zoning regulations prohibited a natural gas compressor station from being constructed even after the industry contested the decision.

Since Cecil Township had local rules governing land use, the company seeking to build the compressor station, MarkWest, was required to appear before the community’s zoning board to gain approval for the project. The company presented plans to the board at several public hearings — meetings which the board and Cecil residents were able to ask MarkWest representatives questions and pose their concerns.

Ultimately, Cecil’s zoning board denied MarkWest’s request for an exception to allow it to construct the compressor station, ruling the company had not sufficiently proven the facility wouldn’t be a detriment to the community.

“Essentially, zoning is a mechanism to protect people from uses that are not compatible with each other,” said John Smith, Cecil’s solicitor, and one of the attorneys who successfully argued parts of Act 13, Pennsylvania’s law governing Marcellus Shale drilling, were unconstitutional due to its ability to negate local zoning laws. “In communities that have zoning, it allows the local governmental bodies to make sure proposed uses are appropriate and compatible with the surrounding population and uses. If they find the uses are not appropriate or compatible, they can deny permits.”

For supervisors like Kingsley, who in the bygone days of fracking saw no need for oil and gas zoning, there’s a new unrest among residents who disagree.

Melissa Troutman contributed to this report.

The statement made by Supervisor Allford is absurd to me. “Like it said in the [local] paper, we all did this to ourselves. Not 100 percent of us, but majority of us signed gas leases. We let these people in here and we gotta deal with it,” asserted Allford.

Would Supervisor Allford invite a person back to his home for dinner after he had found out that they were a thief with a criminal record?

The point is we had no idea what this industry was capable of doing, how much they mislead people, until they started operating in our community. It is not logical to me that after you have found out how much they have misled us that it is still alright for them to continue to mislead us. It is Allford’s type of reasoning that is going to continue to have us misled and abused by the industry.

The statement made by Supervisor Allford is absurd to me. “Like it said in the [local] paper, we all did this to ourselves. Not 100 percent of us, but majority of us signed gas leases. We let these people in here and we gotta deal with it,” asserted Allford.

Would Supervisor Allford invite a person back to his home for dinner after he had found out that they were a thief with a criminal record?

The point is we had no idea what this industry was capable of doing, how much they mislead people, until they started operating in our community. It is not logical to me that after you have found out how much they have misled us that it is still alright for them to continue to mislead us. It is Allford’s type of reasoning that is going to continue to have us misled and abused by the industry.

“We screwed up — we missed a piece of paper,” said Kingsley. “You want us to undo it? How about we all undo it, and we undo our gas leases. The gas company will go away, our problems will go away, and we will all get along.” Several in the audience applauded.

Nothing would benefit the citizens of Pa. more, than kicking this industry out this state, ASAP.

I could not agree more! Let’s get rid of them NOW!

“We screwed up — we missed a piece of paper,” said Kingsley. “You want us to undo it? How about we all undo it, and we undo our gas leases. The gas company will go away, our problems will go away, and we will all get along.” Several in the audience applauded.

Nothing would benefit the citizens of Pa. more, than kicking this industry out this state, ASAP.

I could not agree more! Let’s get rid of them NOW!

At least the DEP does not allow the storage or burial of nuclear waste, or nuclear testing on private property.

Although, DEP does allow the burial of radioactive waste from fracking on private property https://vimeo.com/73672325

So possibly there may be good paying jobs for New Yorkers ahead in the nuclear waste disposal industry. http://bit.ly/1tjF2YJ

At least the DEP does not allow the storage or burial of nuclear waste, or nuclear testing on private property.

Although, DEP does allow the burial of radioactive waste from fracking on private property https://vimeo.com/73672325

So possibly there may be good paying jobs for New Yorkers ahead in the nuclear waste disposal industry.

Just when you think you have heard it all and can’t possibly get any worse…it does! What about those of us that didn’t sign leases? We get poisoned, too!

Just when you think you have heard it all and can’t possibly get any worse…it does! What about those of us that didn’t sign leases? We get poisoned, too!

Get quicker results by by-passing he DEP and Chesapeake. Sue the lease holders and the town officials.

Get quicker results by by-passing he DEP and Chesapeake. Sue the lease holders and the town officials.