“I Turned Blue”: Workers Share Horrifying Experiences Treating Fracking Wastewater

“I Turned Blue”: Workers Share Horrifying Experiences Treating Fracking Wastewater

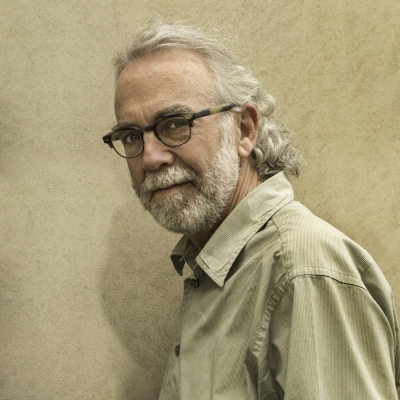

BY JOSHUA BOAZ PRIBANIC FOR PUBLIC HERALD

December 10, 2023

TENORM Series: NPDES Investigations Part 2, a Public Herald investigative news project

December 11, 2023: updated with a letter signed by four of the workers in this story requesting a formal criminal investigation of Eureka Resources, which they sent to Lycoming County DA and PA Attorney General’s offices.

A PUBLIC HERALD EXCLUSIVE PODCAST

SUBSCRIBE

“I felt like I was vibrating and everything turned blue,” Eric Steppe (48) tells Public Herald, recalling a recent injury he incurred while working as a shift leader for a small crew treating oil and gas fracking wastewater at Eureka Resources, an environmental solutions company based in Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

Over the past six months, Public Herald has been contacted by four additional Eureka workers — Quinn Aughenbaugh, Brandon Barrett, Dalton Trahan and Alijah Kibler — who are for the first time sharing their stories about the dangers of treating fracking wastewater.

Across Pennsylvania, there is a system of facilities that takes liquid waste from fracking sites and theoretically clean it, stripping out all harmful contaminants before discharged to waterways. However, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s (DEP) 2016 TENORM study data indicates that these treatment facilities are often not removing even half or, in some cases, any radioactivity before the fracking waste is discharged into rivers.

The industrial companies primarily guilty of this practice are centralized waste treatment facilities, or CWTs. These facilities are owned by private companies such as Eureka Resources and are permitted by the state and federal government to treat and “clean” fracking waste in-house. In reality, most CWTs are not doing a proper job. So they’re failing on two counts: they’re not eliminating radioactivity from the waste and, in some cases, they’re making the waste hotter.

caption: Eureka Resources 2nd Street Plant – 419 2nd Street, Williamsport, Pennsylvania. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

In January, Public Herald reported that DEP’s own data reveals Eureka’s treatment process only removed about 9% of radium from the oil and gas wastewater it processed at its facility in Williamsport.

At Eureka’s Williamsport facility where Eric was hired, wastewater has entered the treatment system “hot” at an average 9,600 pCi/L of combined radium based on the DEP study. After being treated, wastewater tested was only marginally less radioactive at an average of 8,800 pCi/L of radium. These results are a far cry from Eureka’s “pure water” claims, let alone the federal drinking water limit of 5 pCi/L.

What the public has yet to hear is what’s happening to workers in the CWT facilities. When it comes to oil and gas radioactivity, which regulators call Technologically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (TENORM), the EPA itself presents a daunting message:

“Although EPA and others working on the problem have already learned a great deal about TENORM, we still do not completely understand all the potential radiation exposure risks it presents to humans and the environment.”

This report, as evidenced through Eric Steppe’s experience, is one of the first published accounts of those risks inside a treatment facility.

“I got hired at Eureka Resources [as a shift lead] managing a handful of guys and I had high hopes for the place,” Eric tells Public Herald. “But man, I had no idea what kind of a mess I was getting myself into and what kind of dangerous work environment. I’m supposed to report safety issues. There’s no safety, nothing safety, there’s no safety committee. They talk about it, but it never happens.”

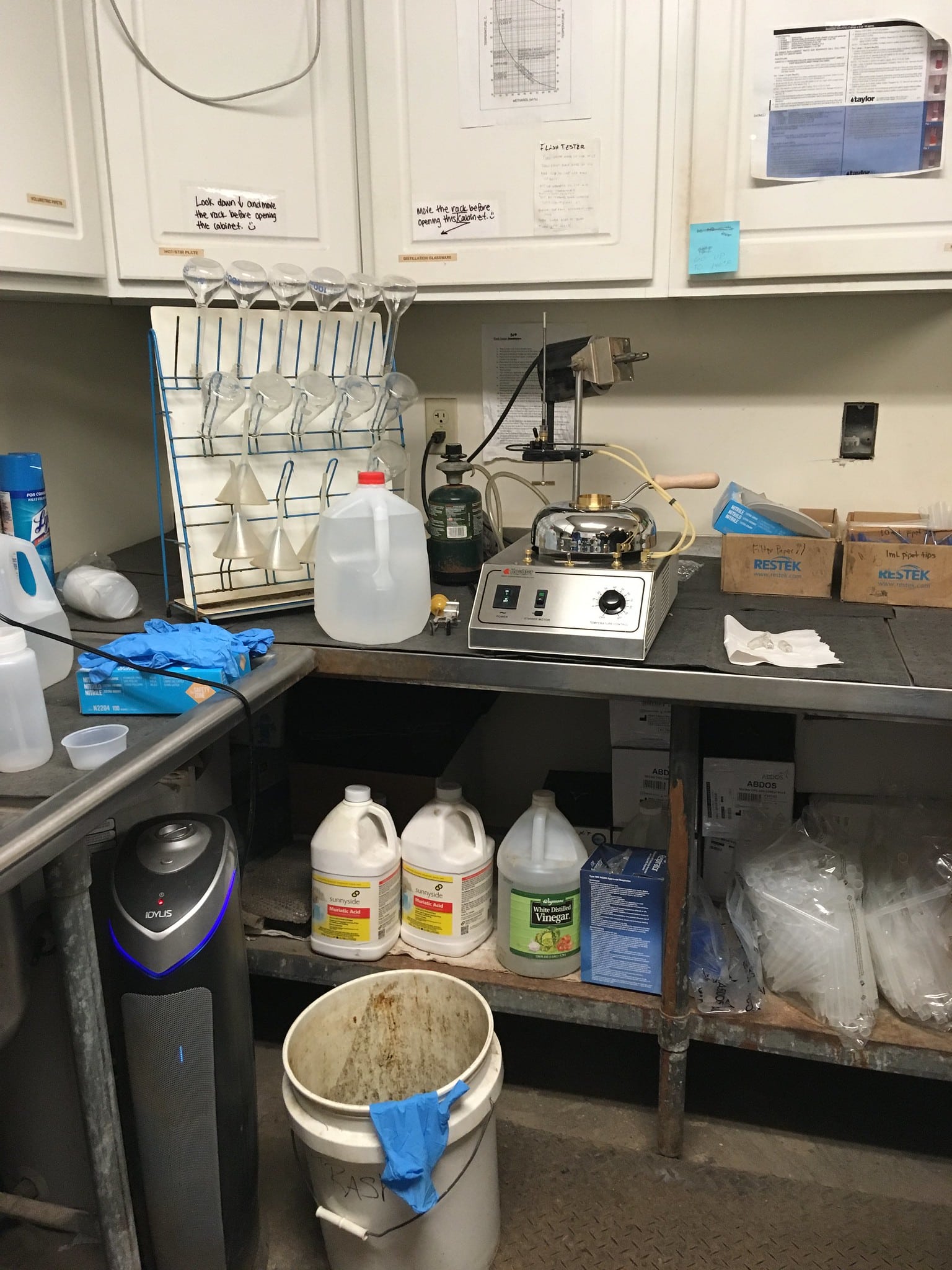

caption: Eureka Resources laboratory in Williamsport, PA in 2019. © Melissa A. Troutman

caption: Eureka Resources waste records at their Williamsport, Pa. facility in 2019. © Melissa A. Troutman

“We had a spill [in August], and I’m still recovering from it,” Eric explains.

“I was cleaning up this mess — there was four of us altogether that we’re cleaning it up — and it was probably a hundred gallons of frack water and oil and sludge and whatever else. And it came out of our one pit and came into the containment area. But of course, nothing works in this place. The drain that’s supposed to get this in case of a spill out of these pits, it’s supposed to go down this drain and into this pipe, and then a pump’s supposed to hit it and pump it into another safe area. Well, of course, the pump doesn’t work because the pipe is clogged.”

“So this is like the third spill we’ve had in three weeks, just in this area, because everything is so full and they keep shoving more trucks down our throat. So we gotta make every little bit of space possible that we can. And we say to our bosses, you know, if we’re gonna do this we’re gonna risk spilling something. And they say, do it. We do it, and sure enough, there’s a spill.”

“So we have this spill and we’re squeegeeing it up, and I’m just crouched down over the drain with a two inch hose as my coworkers and my plant manager squeegee everything towards me. And I’m sucking it up. And we’re outside, mind you — but I’m right down over top of this stuff — and I get a whiff of it, and it messed me up.”

caption: Eric Steppe in the backyard of his home holding the soiled work pants he wore on the day of the accident. (Note: the work pants were washed after the accident) © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

“I got seriously dizzy. I felt like I was vibrating and everything turned blue. Like everything I was looking at was bluish, [it all] had a bluish hue to it.”

“So I got up and I walked over to a post and leaned up against it with my head down. I don’t know how long I was there, but I felt awful. And my coworker Dalton comes over to me and asks me if I’m all right. And I looked up at him and said, no. And that’s when I noticed everything was blue. And he said, you’re blue. He goes, dude, you look awful. And I said, I need to sit down. ” He said, do you want me to take you to the hospital?”

“I said, yes. So I sat down right there on a stack of aluminum. My plant manager comes over to me, Chad, and talks me out of going to the hospital. He says, just lay down right there and get some fresh air. I’m pretty sure I was at death’s door. If I wouldn’t have gone to the hospital and got oxygen and got help, I would’ve been in bad, bad shape. And [my plant manager] just said, lay down right there and, and get some air. Didn’t even care about my health or my safety. Total disregard for it.”

“All he cared about was the mess.”

“Next thing I know, Dalton and my other friend draped me over their shoulders ’cause I’m like a wet noodle, and put me in the company truck, and Dalton took me to the emergency room. And I’m there for the rest of the day. They gave me oxygen, they tested my blood — and I’m completely out of it, I felt totally intoxicated. My limbs were vibrating. My tongue was numb. My lips were numb.”

“I could taste it on my lips, whatever it was. And finally, I went home and I’m still messed up from it. I still have pain in my chest, tightness short of breath, tightness in my head. I can’t focus. You know, I, I’m just, I’m just wiped out. I followed up with my family doctor the other day. She wants me to go see a pulmonary specialist here. I’m just waiting for ’em to call me and tell me when I’m going. It’s not good.”

“I’ve [only] been there eight months.”

“[Two of my coworkers have] only been there like a month or two at the most and they’ve been sick already. This is the work environment that we’re dealing with.”

“I found out through a coworker that at the other plant in Wysox at Standing Stone, a man was flash boiled to death because of faulty repairs on the same stuff that I’m working around every single day [called the] Nomad — it’s a big distiller, and it separates the brine and the water. This guy got flash boiled to where his skin melted off of him, like leather hanging. They’re out in the middle of nowhere and [this guy is] in agonizing pain. And he ends up dying.”

“We have narrowly avoided situations like that at 2nd Street [in Williamsport, PA] where expansion joints have burst — because this thing, when I got there, I walked into everything has been neglected for I don’t even know how long. And now we’ve all been like maintenance guys. I’m not even a maintenance guy. We’ve all been forced to do maintenance because they won’t hire professionals to come in and fix the stuff properly and update the equipment. They just keep using old equipment, ragtag bolts and parts to put these things together. Everything leaks. Oil leaks out of the Nomad engine, which is a giant 12 cylinder engine. There’s a 10,000 pound blower that leaks hydraulic oil fluid. And it’s going somewhere. It’s leaking out and then there’s a lot of it that is going into the distillate that goes into a different tank and then gets sent out into the watershed.”

“When I realized that the oil was going out of this place into our distillate water, which is supposed to be pure distilled water, I was told, “don’t you ever say that there’s oil in the distillate.”

“I’m like, but there is oil in the distillate. What do you mean? Don’t talk about it? Then he says, this is to my face, “We don’t talk about that. Don’t you ever talk about that.” Then he says “there’s always gonna be oil in the distillate. Don’t ever tell anybody that.” I’m like, okay, this is bad. But whatever you say, boss.”

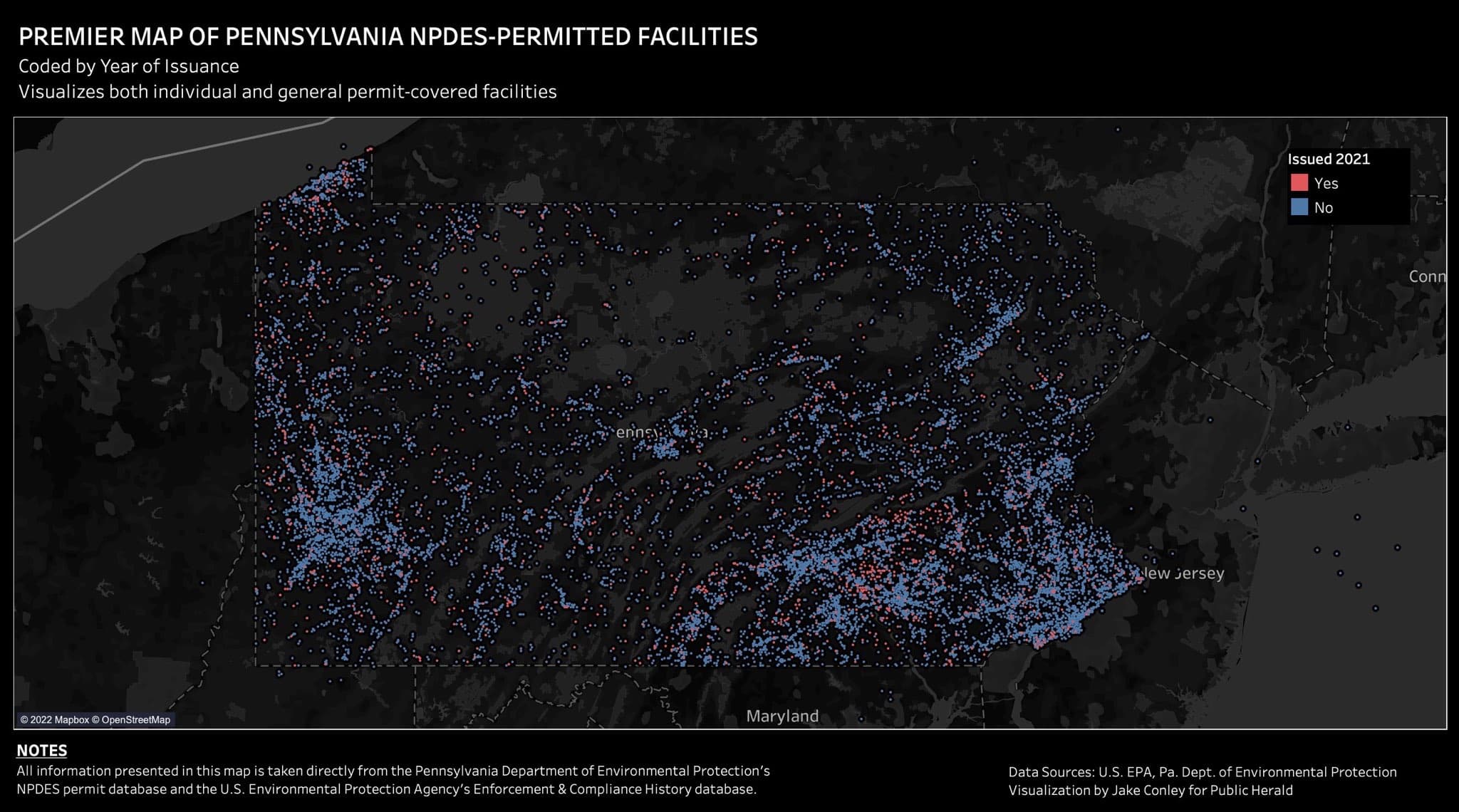

Eureka is not alone in negligent oversight. Public Herald’s 2022 report exposed how there’s a systemic problem with NPDES (National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) permits requiring regulatory oversight for facilities to discharge into waterways.

Eureka’s permit is one of 10,494 total active NPDES-permitted facilities in Pennsylvania. Provided by the EPA and DEP, NPDES permits fall under the Clean Water Act* — they originally aimed to eliminate “the discharge of pollution into navigable waters…by 1985.” Unfortunately, instead of ending the pollution of waterways, the NPDES permitting system actually prolongs it.

caption: All data is based on an aggregation of what’s published by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Geospacial data is taken from the EPA’s ECHO database. Any incongruencies between EPA and PADEP data are the result of data mismatches noted by the EPA here: https://echo.epa.gov/resources/echo-data/known-data-problems#PAalerts. Where applicable, EPA data has been given precedent. Note, individual data points may be difficult to navigate on the map from Tableau. Instead, we recommend viewing the data used for the PA NPDES permit map. © Public Herald

In the case of Eureka, the company claims to “cleanse” the fracking waste in order to discharge the “dewasted” water to the Williamsport Sanitary Authority Central (WSAC), a Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTW), which also uses a NPDES permit to discharge treated sewage effluent to the Susquehanna River.

However, radium, a radioactive component of TENORM that’s water soluble, is not a required part of testing and monitoring under the federal NPDES program. Currently, the NPDES permitting system obfuscates and legalizes radioactive pollution by not explicitly limiting the amount of TENORM that facilities like Eureka Resources can discharge to waterways.

But the federal government gives states the authority to place additional limits on pollutants above and beyond federal standards. This includes limits on radium, which is a carcinogenic radioactive element in almost all oil and gas waste. Despite this threat, DEP has not set a limit for POTWs on the amount of radium that can be dumped into waterways.

caption: Tank at Eureka Resource’s Williamsport Reach Road Plant, 208 Catawissa Ave, Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

From their website: “We completed our newest plant in 2014. This state-of-the-art facility is designed to save millions of gallons of fresh water from being drawn out of the hydrologic system each year by cleansing wastewater and returning it to the original users.”

www.eureka-resources.com/facilities/

© Steven Rubin for Public Herald

Since its founding in 2008, Eureka Resources has crafted an image as a company that breaks industry molds. It lauds itself as having blazed a trail for fracking wastewater treatment, and its vice president of engineering told Public Herald in 2018, “It’s all focused on, you know, generating the cleanest product that can be used for as many things as possible.”

Eureka operates two fracking waste facilities in the state with NPDES permits: One in Williamsport (Lycoming County) and another in Standing Stone (Bradford County). The one in Standing Stone, where Eric mentioned that worker Jeremy Lanzo died from a mechanical failure, DEP failed to include radium limits in Eureka’s NPDES discharge permit. There, Eureka discharges directly to Towanda Creek, a tributary of the Susquehanna River.

Eric’s story graphically illustrates the carelessness about what Public Herald has been reporting since 2018, that NPDES permits are sending radioactive fracking waste into Pennsylvania waterways albeit with state and federal approval through NPDES permits.

Counter to claims by Eureka, DEP’s 2016 TENORM study found that discharges at the facility have tested positive for high amounts of radium.

Further supporting Eureka’s negligence, Eric Steppe states that he has never witnessed testing for radioactivity in the effluent in the eight months he’s been working with the company. And no one in the company has explained the radiation risks associated with the fracking wastewater.

When it comes to DEP failing to limit Eureka’s radium discharge to waterways, Senator Katie Muth (D-44) told Public Herald in August 2022, “I think it’s a criminal act of the government to not require that — that’s gross negligence.”

caption: Senator Katie Muth sits on the bank of the Susquehanna River in Harrisburg, Pa. that makes up part of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. © Steven Rubin for Public Herald

“We have one little I guess you’d call it a Geiger counter or a meter, a radiation meter. And nobody, except for the guys that have been there for a while, has been properly trained on it. We don’t have any specific [adequate] training to use this device to properly test the trucks.”

“But every time we talk about safety, real safety issues, we get blackballed and we get mocked. And we get targeted and treated like shit.”

“We have to add hydraulic oil [to the Nomad] every couple hours because [Eureka’s treatment system is] so shoddy and leaks and it’s just bandaged up,” Eric continues. “We’re getting dripped upon by scalding hot water while we’re doing this. I’ve been burned on my face. I’ve been burned on my shoulders, frequently on my arms.”

“I say a prayer before every time I go under this thing, please God protect me. And, he’s answered my prayers because they have burst and I have not been there. And thankfully nobody else has either. But sooner than later, somebody’s gonna get killed in this place.”

“[My bosses have not] contacted me to even ask me if I’m alive, if I’m okay, and when I am coming back to work. They don’t even care. Instead, I heard from a close friend at work, and he’s ready to walk outta that place because of what was said, [they’re saying] it sounds like sabotage, suggesting that I’m, for some reason trying to sabotage the company. Not worried that I almost died, that I got poisoned.”

“It crushed me. So I’m not keeping my mouth shut anymore. This place needs to be dealt with because human life is completely disregarded. And just the other day you could see H2S (hydrogen sulfide) floating in a cloud through the air. Oh, just don’t go over there — that was their response.”

“So this is what blows my mind. I don’t understand OSHA’s quote unquote regulations, but they were allowing it. It was good enough for them to hear back from one of the managers that they corrected on their word alone, that they corrected these mistakes or safety issues. I read the [OSHA] response letter, and Harry Fulmer was the one that signed it and, and wrote the responses. There’s a few lines in there that I saw where I can positively say they were boldface lies. And that’s good enough for OSHA.”

“They should be coming in there and going through that place with a fine tooth comb. I mean, as soon as you walk into the place, you’re gonna start seeing crazy safety hazards and major codes, violations, and from top to bottom, left to right, there’s nothing safe about the place.”

When Eric returned to work in September, one month after his injury, he was brought into the plant manager’s office and fired.

Eureka Resources has not returned multiple requests for comment.

Stay tuned to Part 3 of the NPDES permit series where the remaining four workers at Eureka Resources share their stories with Public Herald. For more stories about TENORM, go to: https://publicherald.org/tenorm.