“Government Failed You” — Pittsburgh State Rep. Drafts Bill to Stop Radioactive Fracking Waste (TENORM) From Entering Public Waters

Pennsylvania’s 21st District State Representative Sara Innamorato stands on the bank of the Allegheny River upstream from the Department of Environmental Protection’s office in Pittsburgh. © Joshua B. Pribanic for Public Herald

“Government Failed You” — Pittsburgh State Rep. Drafts Bill to Stop Radioactive Fracking Waste (TENORM) From Entering Public Waters

Don’t Have Time to Read This Story…Listen & Subscribe to the Podcast »

SUBSCRIBE »

iTunes | Stitcher | Google Play | Podbean | Radio Public | Spotify | Castbox

by Joshua B. Pribanic for Public Herald

December 10, 2019 | Project: Smoking Gun | Podcast: newsCOUP

Updated: December 11, 2019 to include Earthworks interactive waste map and guide to Clean Water Act lawsuits

Updated: December 16, 2019 to include Fair Shake’s statement on Clean Water Act lawsuits

Pittsburgh’s Freshman State Representative Sara Innamorato is drafting a bill to regulate TENORM (Technically Enhanced Radioactive Material) from fracking waste in response to Public Herald’s leachate investigation.

Innamorato’s effort would take on a regulatory loophole described in Public Herald’s August 2019 report that allows radioactive fracking waste dumped at landfills to be sent as leachate to sewage treatment plants and discharged to public waters. Fracking waste contains high levels of radionuclides known as TENORM which are water soluble and end up in the landfill leachate, but are unregulated and cannot be treated or removed by sewage plants.

Rep. Innamorato told Public Herald that there’s still a lot of work to be done before this effort becomes a bill. But she’s confident her office will produce something with “teeth.”

A lifelong Pittsburgh resident, Rep. Innamorato represents the 21st district in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. She joins a group of newly elected controversial State Reps who oppose fracking in a county with long-standing support for the industry. Innamorato’s “Leachate” Memorandum was released in September and currently has 17 co-sponsors.

Is this real? Is radioactive waste flowing into our waterways?

Yes.

As Public Herald reported, not only is this a reality for at least 15 sewage facilities in Pennsylvania; states like Ohio, New York, North Dakota, West Virginia, and more are playing a part.

Any landfill that accepts fracking waste and discharges leachate to sewage plants would undergo the same pollution to waterways.

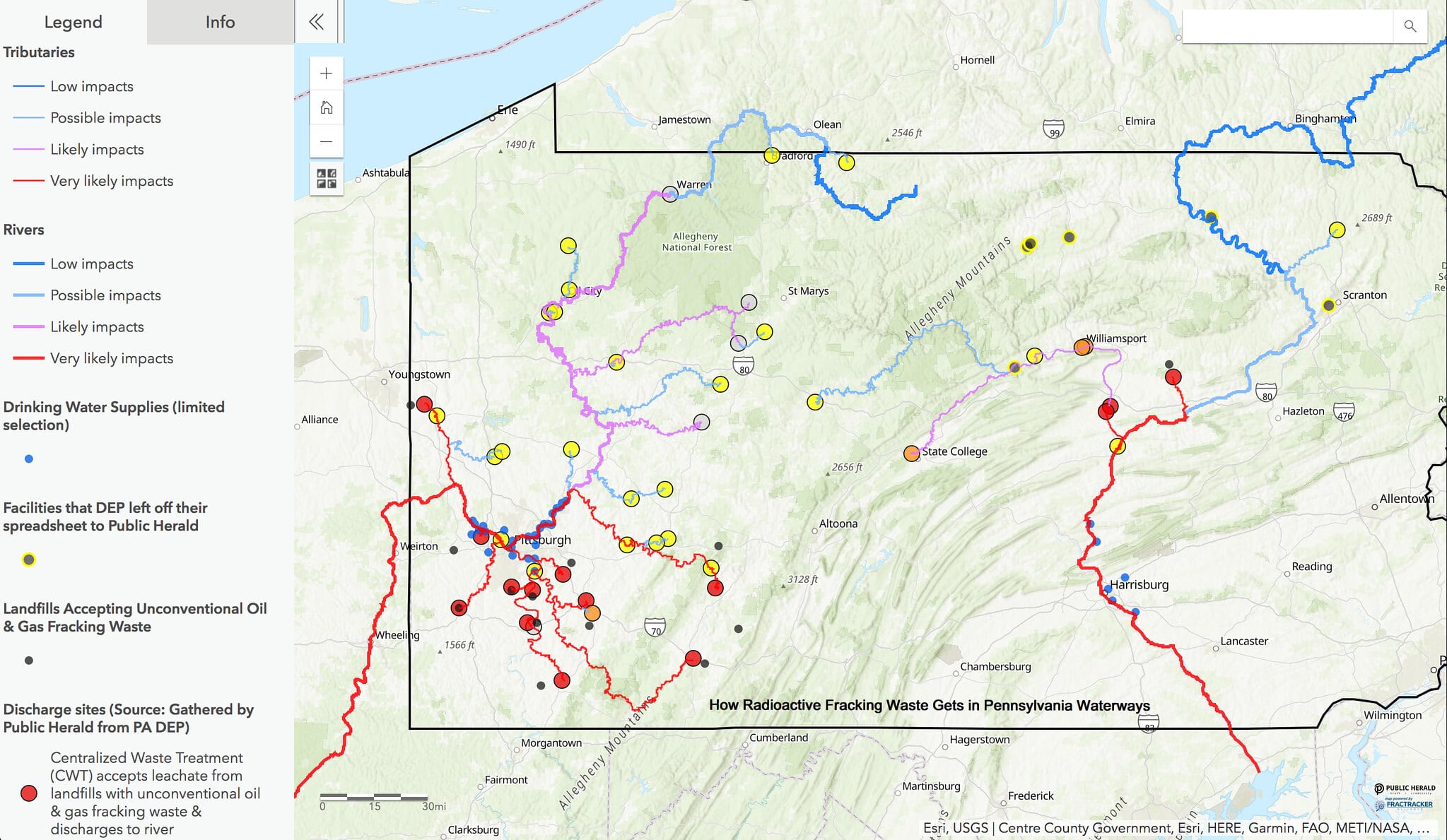

Where and how this is all happening is best illustrated in the Public Herald interactive map “How Radioactive Fracking Waste Gets Into Pennsylvania Waterways” — produced with FracTracker Alliance. Click on the map to view the details. Data was gathered by Public Herald from questions to the PA DEP. Public Herald had to correct DEP on a number of errors in their answers.*

The waste is moving into new areas. Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) came under fire this month for working to change TENORM regulations at landfills in order to accept waste from North Dakota’s Bakken Shale. It’s unclear as of yet where these landfills in Montana will send their leachate.

In Pennsylvania, the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) released a cradle-to-grave TENORM study in 2016 that found radionuclides throughout the life cycle of fracking waste. But these findings were successfully buried, as news organizations and NGOs alike echoed DEP’s 2015 press release: “DEP Study Shows There is Little Potential for Radiation Exposure from Oil and Gas Development.”

Public Herald analyzed the study and found the Department excluded serious environmental health and safety discoveries in public statements. If DEP’s own records are correct, current amounts being discharged to waters of the commonwealth far exceed pollution levels of concern established by the EPA.

Each landfill DEP tested in the study who accepted TENORM from fracking detected radiation in their leachate. In one location Radium-226 was measured in leachate at 378 pCi/L — the safe drinking water level set by the EPA is 5pCi/L. With a half-life of 1600 years, the legacy of radium from fracking will create exposure pathways for centuries in public water sediment if treated by sewage plants.

Soil samples outside of Centralized Waste Treatment (CWT) plants had the same results in the study. CWTs — like the one opposed in Public Herald’s 2018 report — produced levels of Radium-226 in soil at 100 times greater than the concentration limit for uranium mill tailings (5 picocuries per gram) set by the EPA.

These exceedingly high levels of Radium-226 were discovered throughout the DEP study but largely undisclosed by the Department to the public.

Furthermore, DEP wouldn’t reveal the locations of facilities they tested when Public Herald pressed for this information. “I don’t believe there’s a list of every location that was sampled. We don’t actually have that,” DEP regulatory counsel Kim Childe told Public Herald in a 2015 conference call about the study. “I’m not sure how that information helps you. I’m not sure what you’re trying to do and you don’t have to tell me.”

When asked about disclosing records that could explain TENORM risks to the public Childe told our reporters, “We [did] this study to understand how to protect human health. If there was any data showing this is a public health risk we’d be on it.” Childe’s team dissuaded a concerned citizen from pursuing a right-to-know request as a result of their statements on the call.

Can State Regulations Stop TENORM?

© Steven Rubin for Public Herald

“Government failed you,” State Rep. Innamorato pointed out when Public Herald asked for her response to DEP’s study.

But that doesn’t mean there’s no option on the table for states to regulate TENORM.

Under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act’s (RCRA’s) there’s a “domestic sewage exclusion.” It states that “liquid wastes mixed with domestic sewage and discharged to a wastewater treatment plant are not regulated under RCRA, because they are subject to the Clean Water Act.”

The Clean Water Act was created to prevent facilities from releasing any and all pollution to public waterways unless authorized by a permit — commonly known as the “NPDES” permit. However, EPA has not created standards for discharging TENORM to surface waters. But EPA has established TENORM as a pollutant with enforceable limitations for effluent leaving a uranium mill processing site.

If a citizen at any location feels threatened or injured by pollution from the waterways in Public Herald’s report they can file a lawsuit under the Clean Water Act to stop the pollution.

“We refer to [these lawsuits] as a citizen suit. We’ve been seeing shale gas wastewater passing through wastewater treatment plants – both publicly owned sewage treatment plants and centralized wastewater treatment facilities – since 2009. In each instance, we’ve used the Federal Clean Water Act’s citizen suit provision to address the discharges along with state water laws in both Pennsylvania and Ohio. The job of citizen enforcement would be much easier if both the facilities producing and transporting wastewater and the ultimate discharger were publicly disclosing the levels of radioactivity and other pollutants in their influent (wastewater prior to any kind of “treatment”) and effluent (“treated” wastewater). We hope that Rep. Innamorato’s proposal strengthens the ability of citizens to know about these risks and take proper enforcement action when pollutants are being illegally discharged in violation of our strong water quality laws in the Commonwealth.” Emily Collins, Executive Director Fair Shake Environmental Legal Services

“Liquids and sludge may be discharged to a wastewater treatment plant generally through a connection to the sewer,” according to the EPA. “There are no current federal regulations concerning disposal of radionuclides to the sewer. Liquid wastes that are mixed with domestic sewage and discharged to the sewer are not considered hazardous wastes, although wastes trucked to a wastewater treatment plant might be.”

DEP’s study produced TENORM levels sent to landfills in exceedance of limitations set by these federal standards. If enforced, this could qualify the waste for relocation to one of only six facilities in the country capable of handling low level radioactive waste.

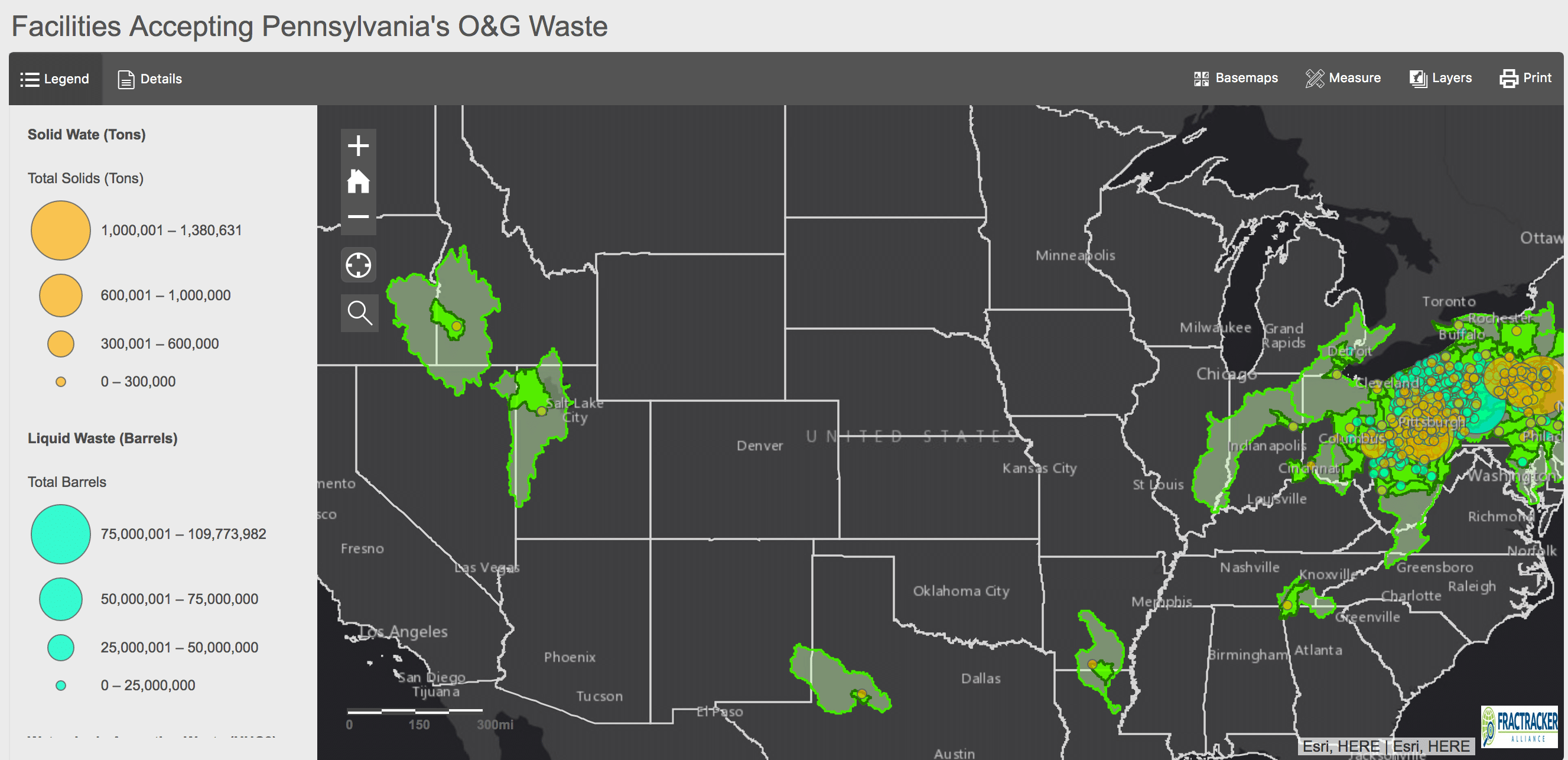

Earthworks produced the Pennsylvania Oil & Gas Waste Report by Research and Policy Analyst Melissa Troutman (also co-founder of Public Herald) which tracks nationwide the facilities accepting Pa.’s oil and gas waste. Click on the image to use the interactive map »

EPA clarifies that, “States that have adopted TENORM regulations that apply to water treatment facilities may also have placed radionuclide discharge requirements on wastewater treatment plants.”

For landfills, “There is no federal requirement to test radionuclide concentrations in solid residuals prior to disposal. However, there are restrictions on the transport of waste that exceeds certain radioactivity thresholds and states and disposal facilities may have requirements for testing or disposal of TENORM.”

EPA’s overall framework for regulations governing radioactive material is not a straight line. For each source or practice the agency divides the responsibility into the following categories:

-

Operations of uranium fuel-cycle facilities (Atomic Energy Act).

-

Radioactivity in drinking water (Safe Drinking Water Act).

-

Radioactivity in liquid discharges (Clean Water Act).

-

Uranium and thorium mill tailings (Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act; Atomic Energy Act).

-

Radioactive waste management and disposal (Atomic Energy Act).

-

Remediation of radioactively contaminated sites (Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, CERCLA; Atomic Energy Act).

-

Airborne emissions of radionuclides (Clean Air Act).

-

Indoor radon (Indoor Radon Abatement Act).

The results of the 2016 DEP TENORM study could have triggered a statewide moratorium on the transport, treatment and disposal of waste from fracking. So why didn’t it?

***

No available license is granted for republishing without explicit permission from Public Herald.

newsCOUP Transcript

Full Transcript of newsCOUP Interview w/ Pa. 21st District State Representative Sara Innamorato

Joshua Pribanic: Welcome back to NewsCOUP everyone. Today we have representative Sara Innamorato from Pittsburgh who has read the Public Herald report and is going to be doing something about the radioactivity involved. So Sara, thank you for coming on NewsCOUP.

Sara Innamorato: Sure, thanks for having me.

JP: So how did the Public Herald report play into what you are doing right now in regard to this issue?

SI: I would say that without it I wouldn’t have known that radioactivity is an issue. Especially when you’re a first year state representative you have a lot that is thrown at you — having to learn the job, learn how to navigate the systems, and then policy perspective. Everything is so deeply interconnected so you’re scrambling and learning, but that report was something I read that really stopped me in my tracks. It was just such a clear example of an injustice happening right under our noses.

If you were to ask any citizen whose responsibility it is to make sure that when industry comes to our commonwealth and they operate in our neighborhoods that they are not poisoning the citizens you would say, well, it’s the government, the Department of Environmental Protection, and when you realize that they are supremely failing in that role, that’s where you would say it is clearly the role of government to step in and make sure that these wrongs are righted and that no radioactive material ends up in our public waterways and therefore in our families and in ourselves.

JP: So, you’re one of the newer elected representatives.

SI: Yeah, I’m a baby rep.

JP: Did you think that the issue of radiation and fracking was going to be part of the beginning of your adventure here?

SI: Not specifically in this role, or through the waste lens and through the radioactive lens. I represent Pittsburgh and parts of Allegheny county and it’s no secret that our air quality gets an F rating every year. I’ve worked in the environmental nonprofit space for a number of years before I decided to run for office, so I thought that I would be more focused on air quality. A big part of addressing air quality is addressing industry regulations. So I thought I would be looking at it more from that sense.

I didn’t even realize that as part of this process [fracking] there is radioactive material that is pulled from the ground. We have not thought strategically about how we handle the lifecycle of this fuel we are producing that’s powering our homes and that’s fueling a downstream industry to manufacture plastics. I thought, I’m just a baby rep of course, but clearly this has been operating for more than a decade in our commonwealth, so someone must have thought of this, right? So we must have this handled.

I was surprised and terrified and saying if no one else is taking on this battle this is something that impacts us all because when we talk about water quality, when we talk about air, those things know no district boundaries, they’re not about our county, they’re not about our neighborhood, or the district number that we represent, it impacts every single one of us. And so the onus is not just on the representative who has the industry operating within their district lines – this is something that impacts us all, so it’s something that I feel right to take up.

JP: It sounds like you have the same kind of alarm and shock as quite a few people that we’ve talked to, in the colleges, people who have been in this for a long time, and even ourselves.

We’ve always understood things to be pretty bad, but when it gets to the point that we’re just actively, annually, discharging radioactive material via leachate into the streams across Pennsylvania, I don’t know how much worse it can get in terms of regulatory shortfalls and misconduct in the state.

We talked about this recently with some professors down here in Pittsburgh who had read the report. They were all under the impression that it had stopped at the rest of the 14 facilities that we mentioned in the report. We outline 15 facilities where this leachate is absolutely going, we say there is more out there, we know that we are definitely doing it, we know that Wayne Township Landfill in PA is discharging leachate somewhere, we have an assumption of where that might be.

The Keystone Landfill in the northeast part of the state we didn’t have on our radar, because when we asked the DEP “who is discharging this unconventional drilling waste leachate via the sewage plants across the state?” the DEP came up with those 15 sewage plants (with Williamsport being added to that list — but with Williamsport not actually receiving leachate but receiving effluent from Eureka Resources who treats fracking wastewater).

What the DEP didn’t include was this Keystone Landfill, which is a massive landfill in the northeastern part of the state, who is also having to take care of their leachate in some way. So the odd thing was, when we brought this up with professors recently, they thought that due to the Public Herald report, the issue had been resolved, that there had been something done about it.

But that’s not the case, we’re not seeing anything being done about it. The DEP has been completely quiet until a couple weeks ago when they asked for a public comment asking for a revision for how this stuff is tested and looked at in the landfill and sewage plants, almost in a way putting the onus and responsibility entirely on the landfills, entirely on the sewage plants, if they are discharging radioactive leachate. But you’re doing something about it, aren’t you? What is it that you are doing?

SI: You bring up a great point that our regulatory environment as it exists is backwards. We issue permits that allow for communities to be impacted by industry and then the onus is on the community to prove that they’re being poisoned or harmed by industry instead of the industry owning the process and saying “No, the chemicals we’re going to use in our process, are safe and they are going to do no harm to the region that we operate in and do no harm to the citizens.”

Outside of blowing up that whole process and saying “how do we change it?” we’re looking at just targeting the specific issue that was raised in the Public Herald report and saying “how do we edit our statute, Title 58 that manages all the regulations for oil and gas in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, to make sure that zero radioactive matter makes it into our public space or public waterways?” That’s the goal. It seems like such a simple straightforward thing to do, but it’s going to be a very heavy political lift. Writing the legislation is just one part of it, then there is going to be this whole other strategy that’s going to involve the public becoming aware of it, getting that message out, making sure they are contacting the people who represent them to bring this bill up for consideration.

JP: So you’re drafting a bill that says “we don’t want anymore radioactive material from the fracking industry to enter the waterways via sewage plants through this landfill leachate. We want that shut down.”

SI: That’s the plan.

JP: And what has been the response to that? How are people reacting to it when you are talking to them?

SI: We’re in the first phase, so in PA what you have to do first is to write a co-sponsorship memo and that circulates but that doesn’t necessarily have the statute attached to it. So when I talk to my colleagues about it they’re kind of shocked and appalled that this happens and they say that it can’t be a real issue and I reassure them that it is a real issue. So it’s getting some traction in that sense. Now what we’re doing is using a co-governing process where we’re working with the experts, the scientists, the doctors, the people who understand this environment, and can come around the table and collectively write this legislation so we make sure all our “i’s” are dotted and our “t’s” are crossed, and we’re not just putting something out that actually isn’t going to have any teeth and not hold the DEP and these industries accountable.

JP: You recently got to see an area where fracking is taking place in Washington county. What was that experience like for you knowing what you know now?

SI: It was really eye opening. I choose to live in the city, I like this environment and I think when folks move out to places like Washington County and more rural areas, they go for the quiet. The first thing that took me aback when I was going on this tour was how prevalent it [the industry] was. You couldn’t look in any direction and not see a well pad. The way the topography works with the ridges and valleys and where everything is drilled, there is a direct impact on the quality of life of the people who are forced to live in the shadows of this industry. I am sure all of your listeners agree that there is a negative public health impact on the individuals who live near where this industry operates, but the light pollution and the noise pollution pose a direct impact on people’s lives and the complete and utter disruption of their lives and potentially the very reason why they moved to that area.

And what are they going to go? It’s either they’ve lived there their whole lives and it’s where their social connections are, that’s where their family is, or who would want to buy their property? Right? Living in the shadows of these facilities. People are stuck. What are they supposed to do?

Someone from Earthworks who was going on the tour with me, recalled a time when she went to an oil and gas industry conference and they had a whole panel on how to operate in previously exploited areas. Pennsylvania, and especially, southwestern PA, has a rich history of being used by industry – whether it was steel here in the city or coal out in the more rural areas, we have a history of being exploited and taken advantage of by industry. And you can see it happening again. It’s very intentional, it’s not by accident that these industries are coming here and wanting to set up shop, its because they’ve done it before and they will continue to do it unless we demand another future.

JP: A lot of this has been manufactured by the state. We have a PA Department of Environmental Protection who as you said is issuing these permits. They’re overseeing the safety of these operations, they’re the ones creating this kind of loophole for the industry to take fracking wastewater, take fracking waste, put it into a landfill, have it magically transition into leachate, and therefore it’s no longer fracking waste and now it’s okay to send it to a sewage plant. What are your thoughts in response to the DEP since this is an agency that’s generally a turning point for people who are facing these risks?

SI: They are not doing their job. If you were to pull someone off the street and say “what do you think the DEP is supposed to do for you and your family?” they would say, “protect the environment, and protect me from any hazards of industry.” And that is not what they’re doing. And that whole thing needs to change.

JP: If we just look at one instance in the report: we talk about the Belle Vernon case with Guy Kruppa. Here he is trying to work with the department to solve the problem with local officials, but in the end the decision is made by the department that “we’re just going to allow the leachate to continue to be pumped into the Monongahela River but we’re going to fine the landfill and make them give us penalty money on a regular basis and that will just go on in perpetuity for however long.” And Guy is standing there beside himself, he’s saying “What are you guys talking about? I just told you this stuff is shutting down my sewage plant. In addition to that I told you that I had it tested for radiation – it’s filled with radioactive material and I can’t treat radioactive material in a sewage plant, so it’s going in the stream and now you’re telling me you want me to pump this into the public waterway, into the public good, every single day, and be okay with that? No way.”

So where do people go? Our answer to this has been that people should try and contact somebody. Contact your district attorney, tell them what’s going on and see if something can be done. Contact the attorney General Josh Shapiro, pressure their office to do something about it. And that has had some results. We have the attorney general in response to hundreds of people calling his office, we have the attorney general at least putting DEP in a grand jury and making them talk about this and we’ll see where that goes in the end and if they’re held accountable. We also have the attorney general looking at the sewage leachate problem so there is potential that he is going where we’re going, which is to all these different plants and trying to find out what’s going on in order to build a case around that. But in the meantime, people are swimming, people are recreating, people are in rivers, and what is it that we tell them at that point?

SI: That government failed you.

JP: Yeah.

SI: And I think if you want to zoom out and talk about the political landscape – a lot of the problems we have come from citizens not trusting their government and we haven’t given them a reason to trust in these agencies and in our governing bodies. Part of this process is trying to restore that trust. We focused a lot on the DEP but we also have to look at our general assembly in this state. We’ve starved the DEP of resources. We’ve gone down this path of austerity that we’ve been on for the last few decades that is just stripping financial resources from all these regulatory agencies that are supposed to be there to support the public good. When these agencies don’t work, or when they fail we look at it and say, “Look, it doesn’t work.”

JP: That’s true, but in the Guy Kruppa situation we’re looking at where they do have those resources available to them and their decision is “No, we’ll just let it keep going, it’s fine.”

SI: I think we have to look at who’s in leadership at the DEP, but not everyone who goes and works at the DEP is some oil and gas pawn. A lot of them are people who want to do the right thing, who want to work in an agency where they protect the public health and the public good and the environment.

JP: Absolutely.

SI: The point of all of this too, is not saying that the DEP shouldn’t exist, but rather we need to make sure that it is an independent body, and one that is not for sale by industry and one that is also fully funded and able to have enough people on the ground to be able to monitor this and make sure that permits are being abided by.

JP: I had a conversation with the former DEP attorney when they were DER, back when they first started, and he was involved with the writing of the Clean Stream Laws and things like that, and I asked him, “What happened at the DEP? It seemed like you guys were pretty aggressive and you were trying to make a difference in this state and make sure that the environment was first in these decisions and the industry had to be held accountable to that.” And he just said that over the years, this was Bob Ging who was just a tremendous attorney in this state, probably the best environmental attorney who practiced, he just said “you know people just seemed to lose the fire in their belly. They were slowed down and it’s not that they got lazier, but that the system became more and more corroded and more and more stripped if it’s mission and it eventually just became like an economic wheel of the industry and a firewall between them and the elected officials.” He said it was this thing that started off with a lot of drive and ambition and things were getting done and then unfortunately it just started to unravel after that.

SI: Yeah, I think about the book Amity and Prosperity. In that book, Eliza Griswold talks a lot about how the DEP agents go from the DEP to jobs in oil and gas in the private sector where they make significantly more money.

JP: Krancer would be a perfect example of that. Former secretary.

SI: We have to make sure that these agencies remain independent and tied to the public good. I think that the work that you are doing with Public Herald, the work that I am doing, the doctors, the scientists, the families who lost children to unknown circumstances or unknown causes of rare cancers, they have nothing to gain by pursuing this. They’re not going to get rich trying to take on this behemoth industry that is producing toxic and radioactive matter and disposing of it like it were any other kind of waste and harmless to the community. We’re not going to make profits from that, we’re not going to get rich, we’re only doing this because we know that it is right, that what is happening is currently unjust and unfair and that we want to do something about it so that we can secure a vibrant future for our kids and for future generations.

We need that kind of motivation again to exist in the public sector and it’s really hard to do that when the pressure to conform once you’re elected is there. It’s there from your colleagues, it’s there from the fact that it requires so much money to run for office, it’s there because when you get to Harrisburg they say that there are 203 reps and there are at least 203 registered oil and gas lobbyists who are there meeting with you, feeding you information. These communities, these families who have lost kids, the doctors, the scientists, the groups doing this research, they don’t have lobbyists, they don’t have money to throw at putting someone into a government affairs position. They’re doing it because of the passion and the drive that they have to solve these problems. there’s a lot that is happening there. Essentially, I don’t know what we do about it, but a lot of it is structural in the ways that we operate.

JP: You are doing something. You’ve taken on going after this bill which is the first of it’s kind that I know of in the state that’s ever been attempted. We’ve been trying to raise the issue of radiation from 2011-13. It’s in the documentary Triple Divide, we talk about it being buried illegally in people’s backyards, through these pits we talk about it getting into people’s water supply, people breathing it in, having the radon that’s associated with the radiation might only have a 3 day half life but it’s not going anywhere when you have it every single day coming out of the waste and coming into people’s showers where they are exposed to it. There’s been a debate about the idea that the radiation won’t be harmful to you if you’re in the water because you’re skin will block it from getting into your body, but then there’s this idea of dermal absorption which is another wave of health studies that show that the radium and other things can enter the body through cracks in the skin and things like that, and pose a problem in the future.

So we’ve been trying to go after this for years now, and you’re the first elected official that we know of whose tried to grab it and do something about it and that’s extraordinary. I think that ties in with your story about how you got elected so maybe you could tell us about that. How did you get into office in the first place? How old are you?

SI: 33.

JP: So you’ve got to be one of the younger reps.

SI: When I was knocking doors I would tell people when they would ask me how old I was I’d say one year younger than Connor Lamb. So yeah, I am what you would call a nontraditional politician or candidate. I decided to run because I was working in the nonprofit sector and I saw more and more that’s who we’re relying on to solve the failures of the public sector instead of actually investing in it. I am from Pittsburgh. I grew up 10 miles away from where we’re at right now, and I decided to step into the political arena not because I was bred to do so but because I had this lived experience of losing my dad to opioid addiction and being in the nonprofit sector and seeing how the system is failing people over and over again and how a million dollar grant is not going to solve poverty. I think when we have people who have experienced the pain and trauma that exists in just trying to survive being an American as it is today, those should be the people who are writing policies, those should be the people at the table saying “I have a voice, I have an experience that is valuable when we’re writing legislation.” That’s what needs to be centered in the process. That’s why I ran. Being an elected representative is infinitely frustrating, it’s extremely hostile in Harrisburg and trying to get any sort of meaningful legislation that is going to result in people-centered structural change passed is hard. But what we have complete autonomy over is how we conduct ourselves in our district office. You can be accessible, you can hear people out. Movements require people so if you’re not being out in the community and meeting people where they’re at, whether its ideologically or physically, you’re not going to bring people into the fold and into the vision that you are trying to build. We’ve also approached the way that we’re writing legislation. I mentioned before that what we’re doing with the leachate loophole bill is bringing people around the table who are the experts out in the community. We can build co-governing tables around the biggest issues that we’re facing and make sure that it’s not just a top down approach from the powers that be, but rather a bottom up grassroots approach that brings a diversity of opinions and voices and lived experiences to every piece of legislation that we’re putting out into the world. And that I think is a really special and unique way right now, but is hopefully something that is going to change as the face of leadership changes in our state.

JP: The solutions that you’re speaking about, it sounds like these are really grassroots solutions that are going to happen through a lot of collaboration and through a lot of work that isn’t necessarily funded by special interests, but a bill will likely be the result. A bill of law will eventually be the change that needs to be made to fix the problem. Do you see room in these situations, because this is not simply a Pennsylvania problem, we’re seeing this happening in Ohio, New York, California, people have reached out to us from West Virginia, Colorado, many different states, where they are suffering the same thing that we wrote about, but we just don’t have the resources to go and investigate other states right now. Do you see opportunity for market solutions in any of that, where the industry might be the answer to some of these problems?

SI: No, industry exists to generate profits for their shareholders, that’s what they’re designed to do, that’s the system of American capitalism that we live under. It’s government’s job, it’s the public sector’s job to say “we are here to protect our shared commons.” Industry is never going to do “the right thing,” that’s why the public sector exists, to be the buffer between the citizenry and the interests of the private corporation. There should always, always be a healthy tension between private industry and the public sector, it’s just the way it exists. It doesn’t mean that the private sector and the public sector can’t come together and come up with a solution, but it should never be at the expense of the citizenry that elected that person to a governing body.

JP: Do you think that we’re looking at market solutions right now? That this is something that’s been created by the market, and not necessarily something that’s been created by the state?

SI: I think that a lot of the environmental solutions that are being proposed are market based. I don’t believe in speaking in absolutes, except when it comes to radiation in our water.

JP: Because that is an absolute.

SI: Yes, that is an absolute scenario. But there could be opportunity where a market solution could work in a certain scenario. But right now, in the climate crisis that we’re facing, that maybe would have been a good idea 20 years ago, but we need to act in more drastic ways. Like this issue that is in front of us right now. It’s not like “Oh well, we’ll stop putting radioactive material in our waterways in 10 years.” If you go ask the people who live around that area they don’t want it in their yesterday. They want it stopped as quickly as possible. So when we rely on market based solutions, there tends to be a longer, more gradual approach. Which again can work for certain things, but not in this circumstance, and not in addressing some of our greatest needs today.

SI: We has a public are going to deal with the legacy costs of this industry and we don’t even know what those costs are going to be. So when we talk about regulation killing industry, what we need to be talking about is what is industry going to cost us 10 years down the road? What is it going to cost future generations? We’re dealing with that now with the coal industry and having to clean up what was left behind, because the heads of that industry made millions and millions and millions and got to retire, maybe set up their own philanthropic endeavors with the millions they were able to amass, and our communities are paying the price both with their health and wellbeing and also with our public dollars which could be going towards schools, infrastructure, healthcare, and everything else that people are expecting the public sector to provide.

JP: And the industry has been so careful in erasing their legacy behind this radiation issue. They made it possible to eliminate themselves from RCRA so no longer do they have to label this as hazardous waste. They made it possible to prevent the radioactive material from being tested within a NPDES permit so if you’re going to get a permit to discharge out of a facility with the EPA or the DEP, it’s not going to require you to test for radiation even though the industry is going to say that everything that goes out and everything that goes in is safe and they test for it, but unfortunately in those cases no one is testing for radiation. So we don’t have test results from the sewage facilities for radiation, we don’t have test results from the landfill leachate for radiation. This was all carefully created and manufactured by industry to essentially erase their legacy and shove it into our own, where as you say, now the public will have to pay for the cleanup of what we find which we’re going to find, we’re going to find these problems out there. And now, not only do we have to address stopping it from being discharged, but we have to go and find out where we need to take it out, and dispose of it properly. It’s just a huge mess that has been kept under the radar for a while now that you just get to walk right into.

SI: What a treat! Whenever we want to propose something that can do good for our community, it’s always, “well, how are you going to pay for it?” And we need to be asking that question now: How are we going to pay for this waste to just be put out into our environment? How are we going to pay for the legacy issues? How are we going to pay for the cleanup? How are we going to pay for the unknown health consequences that are going to occur?

JP: Do you think we’ll be able to get industry to pay?

SI: I have little faith in the way that the system is constructed right now that industry will be forced to pay the full cost of operating. But we’ll change that.

JP: I’m sure there are people listening to this who are really wanting to know how they can help and what they can do. So across the state, what is it that people can do to support you in this process?

SI: I think first, do your homework. Find out who represents you. That information is available with a quick Google search. There is a website you can go to, you can type in your address and find out who represents you. That’s number one. Once you know who represents you, tell them what’s important to you. Tell them that this issue is something that you want them to address and you can send the form letters. They tend to go into a giant folder in my staff members email.

But what really works is scheduling a time to meet with them, making a phone call, writing a personal email or personal letter talking about who you are and why this issue matters to you. Because those really do change hearts and minds, and that actually gives me cover and something to point to when I go talk to my colleagues and I’m like “well, these are the people that you represent who are asking for this as well.” That’s really the best way to help and the best way to grease the wheels to make sure that this can start moving in Harrisburg. But this way it also gets elevated in the public consciousness, because it is something that is extremely unjust and something that, you know, quite frankly could pretty easily be fixed.

JP: Would those people need to ask their rep to be co-sponsoring something, or how would that work?

SI: Yeah, so, like I said, we’re still working on the bill language, but there is a co-sponsorship memo out. So when you talk about this issue you can talk about rep Innamorato’s co-sponsorship memo that she has out about closing the leachate loophole.

JP: And to save them Googling your information, how would they contact you?

SI: For the millenials out there, you can contact me on Twitter I am @Innamo, and Facebook and Instagram under Sara Innamorato. Our email address is [email protected]. The other thing that moves policy is the humanization of it and the only way that we humanize statute is through personal story, so if something as impacted you, your family, your community, we need to hear about it, we need to hear your story because that is an extremely powerful and necessary tool that is going to move the needle on this issue.

JP: Absolutely. I wanted to bring that up that Public Herald will be following up on this story for the next year so anybody who has something to share with regards to their sewage plant or their landfill, where they’ve seen this kind of activity going on, they can reach out to us. They can reach out to my email which is: [email protected] or my phone number which is 4192028503. You can find us on Twitter @PublicHerald, and email is usually best for us, it’s a great way to get in touch. The report that we’re referencing here is publicherald.org/leachate. That was published in August and has a map of all of the facilities that were identified by the DEP that are receiving leachate from landfills and are holding unconventional drilling waste and therefore are releasing some kind of radioactive material into those waterways. You can read that report and find out if you are near there and if your story matches up with that and if it does, please contact us.

There is going to be quite a few people coming on for this in 2020. There is Justin Nobel from Rolling Stone who is one of the few people I know who really has a hold of the radiation issue. Rolling Stone is going to be putting out a report in January or February with Justin that covers this as a whole, potentially across the country and beyond. He is also going to be publishing a book on radiation so definitely follow Justin Nobel on Twitter to stay up to date with what’s going on there.

If you want to donate to our work you can always find us at https://publicherald.org/donate. we always really appreciate the help in trying to get these stories funded so we can do more for all of our readers out there.

SI: Yes, it helps change the law!

JP: Sara, you are such a great resource and it’s so inspiring to hear that you are going to take this on for the public who I’m sure are desperate to hear from somebody like you.

SI: Thank you so much and thank you for all of your work.

JP: Absolutely. This has been NewsCOUP and I am your host Joshua Pribanic and we will catch you next time.